Woodford Folk Festival physically assaulted me for protesting about Palestine... What's the future of events like this?

As we spread across the dancefloor in front of the stage, unfurling our banners and flags, many in the crowd started cheering and clapping, while a few glared, and one person shouted “Sit down!”

Over two hundred people were sitting on white plastic chairs in the massive, humid tent, with more gradually drifting in. It was the second morning of the festival. By this point, most attendees would've already seen a dozen different talks and performances, but this was the first session where a federal Labor government minister was speaking, so it was also the first session featuring a peaceful protest.

When the security guard charged me and my partner without warning, knocking me to the ground, the vibe in the tent shifted abruptly.

This short clip (from a live photo rather than an actual video) is the only close-up footage I have of the assault. Later in this article, I've linked to longer videos filmed from further away.

My adrenaline levels surged. As a darker-skinned man who isn't new to being targeted by authorities at peaceful demonstrations, my first thought was “Oh no, not here too!”

These days, at certain kinds of protests, I almost expect to be shoved and hassled by thugs seeking to suppress our basic rights, but a folk festival is supposedly a peaceful place of free expression. It must have been jarring for a lot of people in the audience as well; this was the first time anyone I spoke to could remember security guards assaulting someone like that at Woodford.

I bounced back to my feet pretty fast, stubbornly returning to my position as the red-faced bouncer kept trying to move me away. A few of the protesters, who’d been very quiet and calm until that point, began yelling angrily at the guards and police.

The flustered MC struggled to assert herself on the mic. “Hey folks, protest is perfectly legitimate” she managed eventually, before going on to thank “our friends in the police and security for being here” and subtly implying that those of us who’d displayed Palestinian flags and held up banners reading ‘Stop Arming Israel’ and ‘Ceasefire Now’ had done something wrong to justify police and security guards shoving and threatening us.

I’ve been coming to the annual Woodford Folk Festival (‘WFF’) for around 20 years, but this was the first time I’d ever experienced violence of any kind. That the violence was initiated by the organisation itself was both shocking and strangely clarifying.

In that moment, I came to understand that despite all my years of backstage volunteering, despite the many times I’d performed as a poet or musician either for free or for a substantially discounted fee, and despite the fact that at the time I also happened to be a high-profile candidate for mayor of Brisbane, the festival leadership didn’t really care about me. From their perspective, Arts Minister Tony Burke’s desire to recite pre-scripted talking points from a festival stage (without the awkward optics of three or four dozen people on the ground in front of him holding Palestinian flags) was more important than my right to peaceful protest and safety from violence.

It was only a push – definitely not a heavy tackle. All I had to show for it was a broken thong, a grazed knuckle and a painful flare-up of an old shoulder tendon injury that subsided after a few hours. But even the police reluctantly agreed that it appeared to meet the definition of a violent assault. The fact that the gang of aggressive guards weren’t immediately ordered away from the venue meant many of us remained on edge throughout the minister’s session.

The guard kept pushing me unapologetically even after I'd fallen over

After the talk, the festival director came over and personally apologised to me for what happened, but in a way that I felt sought to shift blame to the individual security guard, rather than taking direct responsibility. Given that their contractor had just assaulted me, I thought as an apologetic gesture the festival might offer me a free ticket to next year’s event, or at least a couple of free meal vouchers, but they didn’t even offer me a cup of tea.

The director was (understandably) very busy running the festival. I was promised a sit-down meeting with her, but it was repeatedly postponed, and at the time of writing (five months later) still hasn’t happened. I imagine if I decided to sue the festival, they’d be a lot more responsive to my requests.

(I should stress here that I’m not solely blaming the director or any other individual WFF employee for what happened, or for the lack of meaningful follow-up. Everything that occurs in these organisations and spaces is a product of collective decisions and structural forces that impact and ultimately co-opt whoever takes on leadership roles.)

The shove was captured on camera and happened in front of a big audience. The guard clearly hadn’t given us any warning before rushing at me. Queensland Police decided to charge him with assault, and his contract to work at the festival was cancelled (this seemed somewhat hypocritical, because cops routinely behave aggressively towards protesters, but are rarely disciplined for it).

Without the festival administration’s knowledge, I lined up a meeting with the guard a couple hours later. He was crying and distraught – a proven assault charge potentially meant losing his security licence and job, which would also mean falling behind on his mortgage payments.

I intervened and told the police I didn’t want to press charges. Even though he’d been unnecessarily rough with me, I wasn’t interested in the low-ranking employee of a private contractor taking individual blame for the festival’s decisions.

This was because after talking with several of the security guards, it became clear that in trying to push people away from the dancefloor, the guards were acting on direct instructions from the festival.

Who was really responsible for the violence?

I still haven’t been able to get clear answers from festival leadership about precisely who gave the order. But someone – most likely either the stage manager or the festival director herself – instructed guards that protesters were allowed to stand off to the sides of the stage in the corners of the tent, but weren’t to be allowed to stand immediately in front of the stage.

This is why I’ve written that the festival as an organisation assaulted me, rather than accepting their narrative – that this security guard was acting outside his job description and delegated powers and was solely responsible for an action he hadn’t been authorised to take.

In supporting the police to press assault charges and ending the guard’s contract to work at the festival, organisers were making him the fall guy for a situation they had created...

- They had given a federal Labor government minister a well-publicised festival platform at a time when the wider Australian public was increasingly frustrated about Labor’s support for Israel’s invasion of Gaza

- They knew very well that there was a chance of protests, so decided to ask cops and security guards to be present at this particular venue for the minister’s talk

- And they gave the instruction that protesters should be prevented from standing immediately in front of the stage while the minister was speaking, knowing that cops’ and guards’ main tools for controlling crowds all involve threatening or using violence.

Festival leadership might not have explicitly told the guards to push protesters away from the stage, but from talking to the guards themselves, they clearly understood that this was what was expected of them. If you direct a guard to prevent people from remaining in a particular location, knowing some of those people might refuse verbal directions, you’re creating a situation where the guard feels they have no alternative but to use force to move them on.

One of the guards (not the one who pushed me) told me later he’d been specifically instructed to prevent any protesters climbing onto the stage. No-one did attempt to get onstage (we just wanted to stand down the front holding banners and flags, then ask some questions in the Q&A segment) but he was of the understanding that if someone did jump up there, he would have to physically drag or push them off again.

The presence of both police and private security guards certainly didn’t increase safety, and served only to escalate tension. I would not have been assaulted if the festival hadn’t called in the guards and cops.

The loose network of people who participated in this peaceful protest action represented a fairly broad cross-section of the festival community – a mix of performers, volunteers, and paying ticket-holders – who’d decided at short notice that we should organise some kind of demonstration against the Labor minister.

We didn’t intend to actually disrupt or shut down the talk (which, for a bunch of musos with access to loud instruments, would have been very easy) and participants only reacted with chants and shouting after the ham-fisted attempt by police and guards to move us away from the stage.

Perhaps this point needs to be emphasised, because when guards or police use violence, the wider public is primed to assume that the target of violence must have done something specific which somehow triggered or justified the attack. As the footage shows, before this assault at Woodford, I hadn't shouted a single word to interrupt the minister before I was pushed over. Literally all I did was stand in front of the stage (where festival-goers often stand), holding a Palestinian flag.

But even if the protesters had been slightly noisier and more disruptive, that would not have justified the festival sending in guards and cops to control where we were and weren’t allowed to stand.

While emphasising how unreasonable it was for guards to push me without warning just for holding up a flag, we also need to avoid falling into the trap of implying that if I had heckled the minister, this would have excused the use of force against me.

Did Woodford learn anything from this?

In the long history of suppression of peaceful protests in Queensland, this incident probably isn’t even worth a footnote.

But one reason I wanted to write about it is that, based on my very brief conversations with senior festival staff, it sounded like their takeaway was not: “Oh actually it’s completely unreasonable of us to prevent protesters standing in front of the stage when a politician is speaking.” It was: “We should have done a better job of clearly communicating to protesters where they were and weren’t permitted to stand.”

The naivety of this conclusion should be obvious to anyone who has ever been involved in organising peaceful protests. Are Woodford organisers seriously suggesting that the next time a government politician comes to speak at the festival, protesters who are directed by the MC to stand in the corners of the venue (where the politician can’t even see them) are going to dutifully comply? Surely not!

The next time a government minister is given a platform, festival-goers will again attempt to display banners in front of the stage. Presumably, festival leadership will again ask security guards or police to use force to exclude those festival attendees from a space they would otherwise be free to gather in. This will almost certainly lead to more tension, disorder and disruption.

It’s decisions like this – about whether to prioritise a government politician’s comfort over the public’s rights to peaceful protest – which effectively test and reveal where an institution’s allegiances lie.

Overall, the festival leadership’s response to Palestine solidarity activism throughout the event was pretty poor.

The organisation was evidently receiving several complaints from Zionists about the visible display of Palestinian flags and anti-invasion messaging. Rather than being dismissed as exaggerated and unreasonable, these complaints appear to have had a real impact on decision-makers who seemed – based on the way they handled it all – to be way out of their depth.

Festival attendees established a vigil for murdered Palestinian journalists, but senior festival staff confiscated the ‘Woodford for Palestine’ banner, suggesting it was divisive and that they didn’t want to be seen to be ‘choosing sides’ (even though it’s obviously not their prerogative to dictate how the word ‘Woodford’ can and can't be used).

This absurd article (which isn’t worth reading in full) exemplifies the hyperbolic and disingenuous claims Zionists were making: that criticism of Israel’s invasion is inherently anti-semitic, and that the mere presence of pro-Palestine symbols and chants allegedly made Jewish festival-goers feel ‘unsafe’ (see Randa Abdel-Fattah’s incisive takedown of such nonsense). Having just been physically assaulted while participating in a free Palestine protest, I found Zionists’ complaints about feeling unsafe particularly galling.

Numerous Palestinian writers (see e.g. Sara Saleh’s excellent essay) have highlighted the persecution of pro-Palestinian artists and the complicity of Australian festivals and arts organisations in silencing criticism of the ongoing genocide.

Broadly speaking, Woodford’s response was slightly better than some major arts events – it didn’t explicitly reprimand or discourage performers who waved Palestinian flags, for example – but it still capitulated heavily to pressure from Zionist lobbying. I had a truly exasperating conversation with one senior festival employee where he repeatedly insisted that Woodford was an ‘apolitical' event, even though it routinely gives Labor government politicians a platform to make speeches. Ironically, he was wearing a Sea Shepherd cap at the time.

The festival certainly failed as an organisation to speak out against the genocide or stand in solidarity with Palestinians, and fell into the too-common trap of seeing ‘neutrality’ as a virtue – as though both ‘sides’ are equally at fault. Confiscating the home-made ‘Woodford for Palestine’ banner sent a pretty clear signal to attendees of Palestinian origin.

This collaboratively-drafted statement of concerns (which I don’t think the festival ever responded to publicly) gives you a flavour of the broader frustrations many of us were feeling.

But rather than focussing on WFF’s deeply disappointing refusal to stand with Palestine, or specifically on how it handles protest actions, what interests me most about this fiasco is the way it highlights a much broader tension between the kind of event that Woodford purports to be, and the kind of event it has actually become.

Who is the festival really for?

Like most major events and cultural institutions, Woodford’s identity and vibe is collectively shaped and contested – even me writing this article is part of that ongoing push and pull. But in recent years, the dissonance between what the festival seems to be, and what it actually is, has become stronger and more obvious.

On the one hand, the festival presents itself as an inclusive space, open to people from all walks of life. But this year, even the ‘discounted’ early bird season camping tickets will be $641 (including booking fees). If you’re not camping and just want to come for a day, a presale one-day ticket is $146.

While those prices are arguably ok value considering the amazing quality and breadth of the program, they’re prohibitively expensive for a lot of people, especially once you add in extra costs associated with camping, food and travel. Consequently, the majority of paying patrons are middle/upper-class white Australians.

The festival’s volunteer base is more socio-economically diverse, but the festival doesn’t provide free childcare for volunteers with kids, and many roles are only accessible for able-bodied, neurotypical people. For a lot of younger adults, taking a week off your paid job to work 6 hours/day unpaid (while still having to cover your festival meal costs etc.) is a much less attractive option now that rents are far higher than they used to be. The festival has struggled to recruit enough experienced volunteers in recent years – a growing problem across the events industry more generally.

So we end up with an event that tells itself a story about being a space for everyone, but actually excludes lots of people with its huge paywall.

Over time, the festival’s comparatively privileged upper/middle-class ticket-payer base has been reflected in decisions about what Woodford does and doesn’t invest in and how the event is delivered...

Most campsites now have the luxury of hot showers and flushing toilets, whereas hard-working Auslan interpreters still aren’t paid for their time.

WFF spends hundreds of thousands of dollars each year for private security guards and Queensland police to attend the festival (weird huh? I thought our taxes were already paying cops’ salaries) while many musicians and presenters offer their services for free or well below their usual rates just to get onto the programme.

Woodford’s costs and logistical challenges for accommodating larger and larger campsites also keep rising (on average, wealthier patrons tend to have bigger camps and more private vehicles than lower-income patrons). Parking on site costs as little as $20 for the week, whereas the festival shuttle bus just to Caboolture train station still costs $40+ (return) per person, encouraging and rewarding patrons who drive.

Rather than non-profit communal cook-ups, food within the festival is sold by for-profit businesses, whose high prices reflect the inefficiencies of individualised catering. This in turn means festival-goers like me bring more vehicles and burn more fossil fuels to transport even more camping equipment just so we can prepare affordable meals at our tents instead.

I could go on with many more examples. It’s hardly surprising that a major festival that preaches sustainability and inclusivity while operating under neoliberalism is riddled with contradictions like these. But perhaps the even bigger disconnect is between the festival’s creative programming, and the types of presentations and forums it hosts.

Radical artists, conservative presenters

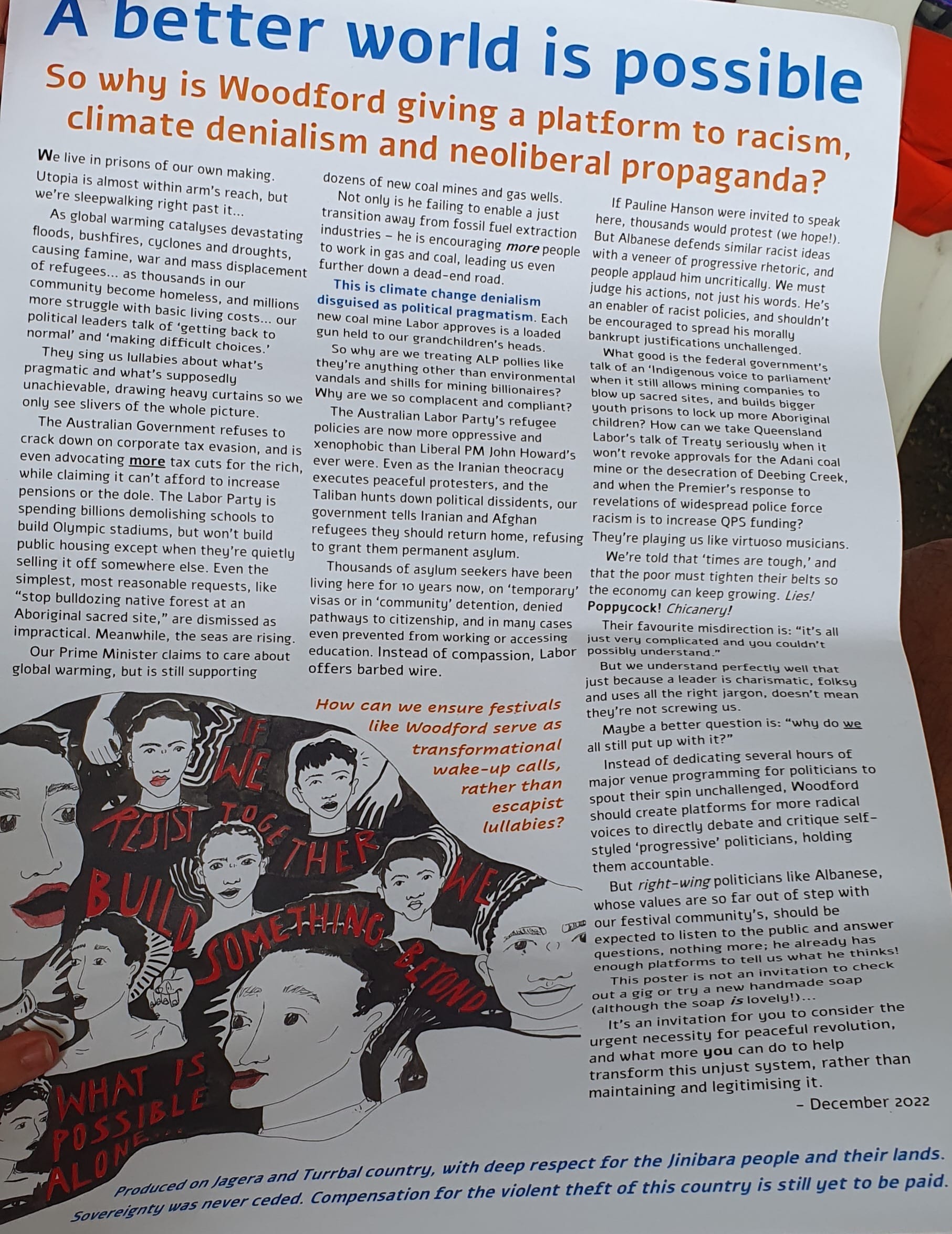

Woodford’s performing artist lineup is full of acts who advocate major social change, and offer explicitly political critiques of consumerism and ecological destruction, the fossil fuel industry, settler-colonialism, prisons, police, militarised borders etc. This reflects the long history that folk music, dance and storytelling have played as mediums for social critique and political agitation. Yet these artists generally aren’t matched by talks and workshops covering equally revolutionary content...

A folk musician sings about how we need to blockade native forest logging or collectively disrupt coal mines – powerful actions to change whole systems. Meanwhile, many of the environmental talks at the Evergreen Stage focus on small-scale personal actions to reduce individual waste or add more native plants to your backyard (not that these things aren’t important, but the simultaneous absence of any talks teaching people how to organise a workplace strike or lock on to a bulldozer is telling).

Hip-hop MCs rap on stage about police brutality and quote Aboriginal activists, but those movement leaders aren’t invited to give presentations. Instead, the most prominent Indigenous speakers on the programme are conservatives like Noel Pearson.

It was particularly jarring at the 2022/23 festival seeing the Spinifex Gum choir sing about deaths in custody and the destruction of sacred Aboriginal sites on the same stage where Anthony Albanese – who actively defends policies that perpetuate such injustices – was given a platform to promote himself.

To be fair to Woodford, last year’s programme did include one talk titled ‘How to get capitalism out of your head,’ and they also gave me a 50-minute slot to speak on ‘The radical potential of local councils.’ Some speakers, such as Aunty Mary Graham, offered insightful critiques of settler-colonialism. But these were lower-profile exceptions to the general pattern, whereas the well-publicised speakers on the largest stages were consistently much more centrist.

After much reflection, I've concluded that this juxtaposition of ostensibly radical artists with reformist, counter-revolutionary presenters (who tacitly legitimise or even directly defend settler-colonialism and neoliberal capitalism) is not just oddly incongruous. It might be actively harmful to broader movements for social change.

Think about how the average audience member experiences this: You go to a festival and watch your favourite musician sing about injustice and the need to rise up. You feel inspired to take big actions to change the system. Then you go watch a lecture from a government minister or centrist academic who reinforces the status quo narrative that deep, structural change is impossible and protesting doesn’t solve anything (but you can send your local MP an email if you like).

Some readers will no doubt point out that government funding conditions might restrict the kinds of talks the festival can feature. But if nothing else, it’s striking that in the last couple of years, Woodford has platformed numerous Labor politicians, and not a single state or federal Greens MP (even though since May 2022, the Greens actually have more federal MPs in Brisbane than Labor does).

This is one of the biggest contradictions at the heart of the modern Woodford Folk Festival – an event with many of the trappings of utopian, anti-establishment counter-culture, but which teaches people that ‘rising up’ simply means shopping ethically and maybe signing a petition backing subsidies for corporate sector renewable energy investment.

This is not just about Woodford

Of course, while the contradictions at Woodford Folk Festival are especially striking, the underlying tensions are common to most major arts and cultural events. I’m not writing this piece as a call to boycott Woodford (personally I've applied to perform at the festival again this year, and hope to get in... let's see), but as an invitation to consider what role festivals and arts events like this really play in society, and what utopian futures they might be crowding out and obscuring.

For one week of the year, tens of thousands of South-East Queenslanders, and thousands more from other parts of Australia and across the world, converge to party, share ideas and perhaps experiment with different ways of existing and relating to each other. It’s not as if all those people could easily coordinate to take another week off work for a second, more radical festival.

So Woodford occupies a particular niche in our cultural and political ecosystem and calendars. Right now, it uses that niche to offer participants an experience which is often superficially subversive, but is in fact fundamentally reformist and counter-revolutionary.

Folk festivals can – or should – serve as giant labs for socio-cultural experimentation, where we can step outside the norms of individualistic capitalist consumerism and settler-colonialism to temporarily create different kinds of communities that are less hierarchical, more caring and more creative. But if these events disguise themselves (whether intentionally or unreflexively) with the aesthetics of counter-cultural utopianism, while stifling political dissent and paying cops and security guards to defend establishment commentators, they end up maintaining the status quo rather than reimagining it.

So are events like Woodford mere hedonistic pressure valves, where we all have a party to temporarily forget how bad everything is getting? Or are they serving an even more sinister function – a sleeping potion that mis-educates us, normalising capitalism, leading us down ineffective pathways for social change, and narrowing our imaginations of the alternative possible futures we should be fighting for?

It's the end of the (festival) world as we know it

Hard truths time: Big festivals are struggling to remain financially (and socially) viable.

We've all seen the growing list of major festival cancellations resulting in part from rising event production costs and in part from cash-strapped punters having less disposable income for tickets. If the State Government started funding non-profit arts festivals at a rate that properly reflects the value they provide to society, the balance sheet would look a little less shaky (noting that Woodford does already get more government funding than most for-profit festivals).

But on top of those general challenges, Woodford is a mid-summer camping festival in a part of the world that’s increasingly vulnerable to both heatwaves and destructive storms. In recent years, mere predictions of severe heat or heavy rain have proven enough to collapse ticket sales. To suggest that a late-December outdoor festival of this style and scale will still be able to attract and safely accommodate large audiences 10 or 15 years from now is either wishful thinking, or outright climate change denialism.

One way or another, Woodford is going to have to evolve. The wealthier middle-aged and elderly patrons who make up a significant portion of its customer base aren’t going to keep crowding into stuffy tents when the temperature consistently exceeds 45 degrees and humidity climbs above 75%.

And progressive young people aren’t going to put up with storm-soaked campsites or long shifts in the sun volunteering for a festival that calls security guards on them just for holding up flags and protest banners, while spending tens of thousands of dollars paying police to stalk the grounds looking for trouble.

Coming from the perspectives of both a regular, long-term festival volunteer and an under-paid performing artist, I feel comfortable donating my time to an event that feels like it’s helping change society for the better. A massive creative convergence that platforms innovative artists while fostering vibrant political discourse, uplifting marginalised ideas, and experimenting with alternatives to individualisitc consumerism is worth volunteering for.

But if Woodford is to be just another stock-standard music festival that relies on the work of unpaid bar staff to cross-subsidise ticket prices for ‘apolitical’ heat-struck hedonists, perhaps we should ask ourselves what the broader point is.

Can this festival reinvent itself, and transform into a space of genuinely utopian creative experimentation and artistic rebellion?

Or will it ossify into a risk-averse getaway that a shrinking middleclass escapes to for a week to passively consume feel-good music, food and non-threatening ideas while the rest of the world burns?

That's up to all of us to decide.

For those who haven't realised yet, writing a piece like this is a fairly risky move for an independent musician in my position. Publicly critiquing a festival like Woodford could have significant ramifications for me, not just in terms of whether I get booked to speak or perform at WFF again, but indeed for how I'm treated by other curators and programmers in the wider arts industry. If you believe it's important for writing like this to be freely available to the wider public, please consider signing up for a paid subscription to help fund me to produce more of this kind of work (and to keep making music and poetry, even if some of my favourite festivals decide not to book me for shows anymore due to my political views).

Note: Before publishing this article, I repeatedly contacted Woodfordia Inc. by phone and email to request comment (in addition to the previous correspondence I'd had requesting a meeting with the festival director). Last week I emailed the festival a list of questions and a full draft of this article, offering them the chance to respond and promising to publish their reply in full. I received confirmation over the phone and via email that they had received my email, but they declined to respond to the questions. I did notice that at some point (I'm not sure when) WFF seem to have blocked my public Facebook page from their social media channels. So much for being open to constructive criticism!

If Woodfordia Inc. does get back to me at some point with a response, I will update this article to include it. If you're a fan of Woodford and would like to see the organisation respond to the concerns outlined in this piece, I suppose you could email them at info@woodfordfolkfestival.com to see what they say, but I wouldn't hold your breath for a meaningful response.

Finally: I wanted to acknowledge that the ideas in this piece are collectively produced and have emerged through many conversations with other members of my artistic/activist community. I'd particularly like to thank my partner Anna for all the great chats we've had about Woodford over the years, including the shows we did about it on 4ZZZ's Radio Reversal program, and for introducing me to writers like Mark Fisher and Dylan Rodriguez (whose work is definitely worth checking out if you want to read more about the way reformist spaces neutralise revolutionary movements for social change).

Just in case anyone's curious, below you can find the longer 9-minute version of the clip showing the before and after context of when I was pushed over during the protest at the Minister's talk. Thanks for reading!

(Seriously, please do sign up for a paid subscription if you can.)

Member discussion