Save Wallum: A radical struggle against destructive 'development' (Part 2: The politics of resistance)

(This is Part 2 of analysis and commentary on the political significance of the Save Wallum campaign in the Northern Rivers of NSW. For an overview of the development proposal and the campaign itself, read part 1 here, but you can also read this article as a standalone piece)

We’ve all seen the cliché news stories showing unhappy residents (“look grumpy!” the photographer advises them) holding signs or standing with their arms crossed in front of trees that are facing the chainsaws or an old house that’s about to be demolished.

Usually, these campaigns die out as soon as the final approvals come through.

People lose hope and give up.

I must have posed in at least a dozen different photos like these ones over the years

But when Clarence Property secured an approval to clear ecologically significant Wallum heathland for a residential subdivision, instead of melting away, Brunswick Heads residents set up a blockade.

In doing so, they’ve taken on one of the most powerful industries in the country.

And they might actually win.

"It feels special, you know? I think everybody who comes here really appreciates that. The developer obviously appreciates it for a different reason." – Sarah Ndiaye, Deputy Mayor, Byron Shire Council

Campaigns against other kinds of developments – stadiums, mines, dams, highways etc. – often have a different flavour, both because the government usually has more power to directly cancel a project (even after it’s underway), and because the arguments against private construction of for-profit housing are a little more nuanced and multi-faceted...

Resident campaigns against unsustainable, profit-driven residential developments are one of the most common forms of local community activism across the country. They’re often unfairly mischaracterised as NIMBY struggles undertaken by ‘privileged’ residents who don’t want their property values to fall.

Certainly you can find some resident groups that are motivated purely by self-interest and classist 'not in my backyard' opposition to more low-income people moving into their neighbourhood. But in my 7 years of experience as a city councillor, those kinds of people are a small minority.

In reality, community campaigns against residential developments are usually motivated by a range of legitimate concerns including tree removals and native habitat destruction, exacerbated flood risk, insufficient public transport and car-centric planning (and the ensuing traffic impacts), replacement of cheaper homes with newer, more expensive ones, loss of heritage architecture, unsustainable building design, or excessive impacts to visual amenity or solar access.

Underlying most objections to new development is the persistent, well-founded concern that the property industry isn’t contributing enough towards local improvements catering for population growth. Private developers pocket the profits, while the wider public has to bear the ever-increasing cost of new infrastructure such as schools, healthcare facilities, parks, sports fields, community centres, libraries, transport services, mains water, sewerage, electricity, telecommunications etc.

It makes sense that communities would push back.

Do these campaigns ever win?

Most community campaigns relate to projects that largely comply with existing planning codes (which have been written to suit developers, and so are very permissive), meaning court challenges to an approval are either impossible or unlikely to succeed.

Occasionally though, the weight of submissions, petitions, court actions, angry letters to politicians and sometimes even protest marches is enough to pressure decision-makers into rejecting a particular development application or even an entire planning code amendment. The long-running and recently victorious Toondah Harbour campaign in the Redlands stands out as the largest and most significant recent example of this.

Sometimes the changes a council or state government requires of an applicant (e.g. reducing building heights or preserving more green space) will make a project unprofitable – the developer will quietly abandon it despite it being approved. Or the threat of sustained post-approval protests is enough to put the brakes on a project for several years (as was the case with 5 Dudley St, Highgate Hill until recently).

Most often though, developments seem to go ahead in spite of public opposition, and only very rarely do protests continue after a developer receives the final approvals.

While blockading other kinds of developments – particularly roads – is much more common, I can only find half a dozen examples in recent Australian history where campaigns against residential development projects have included organised, directly-disruptive blockades after work begins… (If you know of others not mentioned here, please let me know)

In Brisbane in early 2016 (before becoming a city councillor), I joined a couple dozen Highgate Hill residents in briefly blocking demolition of several pre-1911 sharehouses, which had provided affordable accommodation to low-income renters, and were being replaced by more expensive apartments. Later that year, we blockaded driveways of the West Village construction site after it was approved by Labor Deputy Premier Jackie Trad.

On both occasions, community opposition (including turnout to evening and weekend meetings) was strong, but very few participants were able or willing to take time off work for weekday protests, or risk arrest to stop the projects going ahead once approvals were granted.

Over in Western Australia, City of Rockingham residents offered much stauncher resistance in 2017, blockading and disrupting residential subdivision developments that were destroying coastal sand dunes at Golden Bay, south of Perth. But the turnouts weren’t large and well-coordinated enough to keep the bulldozers out altogether, and mass participation dropped off after clearing began. Someone did give the contractors a parting blow, setting fire to multiple pieces of heavy machinery the night after dune clearing ramped up.

Very occasionally, we've also seen the odd smaller, lower-profile blockade action, such as in northern Brisbane in March 2023, when a small but committed crew of northern suburbs residents briefly held the line against tree clearing on the edge of Brighton Wetlands (for a relatively small 9-lot subdivision), but eventually complied with police directions to move.

By far the most significant and long-running modern disruption campaign against residential development in our region was the First Nations-led struggle to protect Deebing Creek, south of Ipswich, where multiple protection camps and snap blockade actions held the developers’ bulldozers at bay for almost four years after development approvals were granted in 2019.

The broader struggle against profit-driven redevelopment of Deebing Creek had been running ever since the European invasion began (with various occupations by Aboriginal families continuing right up through the 1980s and 1990s in defiance of the colonial legal system), but in the absence of enough local community support around Ipswich, there wasn’t sufficient political pressure for a ministerial call-in or government buyback. Some of the elders connected to the site were also less supportive of direct action approaches such as machinery lock-ons and tripod sits, which limited the campaign’s tactical options. The majority of Ipswich residents were barely aware of the campaign, and most supporters on the red alert lists lived in Brissie, more than a 45-minute drive from the site. A succession of violent early morning raids by police eventually evicted the protectors and allowed the bulldozers through.

Many other major community campaigns – such as the push against the West Byron subdivisions – have used a range of advocacy and protest tactics (often winning positive partial improvements) but have stopped short of initiating serious blockades once approvals came through.

Going back to 2002, we can point to the tree-sits and occupations to resist redevelopment of Highgate Hill’s largest remaining vegetated gully, which kept the bulldozers at bay for about a month after approvals were granted (although the retention of Brydon St Park could arguably be described as a partial victory).

Much further south at Sandon Point (10km north of Wollongong), a long-running campaign starting in the early 2000s against a Stockland housing development included establishment of an Aboriginal tent embassy and multiple community pickets and blockades. Discovery of the body of a Kuradji (an Aboriginal ‘clever man’) – exposed by sand dune erosion in 1998 and dated at around 6000 years old – slowed development plans for years, but community opposition wasn’t enough to halt it forever. Subsequent stages of development – including a major retirement village – are still proceeding, but the campaign did leave a broader positive cultural and political legacy for the community.

And of course if we look further back in time, we get to North Queensland’s Daintree Forest blockades of the 1980s (which primarily targeted a road project but also opposed forest clearing for residential development), and Sydney’s rich history of green bans during the 1970s.

But in recent decades, the only really successful campaign anyone seems to remember which involved directly blockading green space destruction to prevent an approved housing development was at Byron Bay’s Paterson Hill back in 1999, which culminated in 200 arrests (most participants were released without charge) and Greens councillor Richard Staples climbing onto a bulldozer. After a few years of court challenges and further lobbying, the site was publicly acquired and eventually incorporated into Arakwal National Park – a massive victory for direct action. A key difference on that occasion was that Byron’s Greens mayor at the time was firmly opposed to the development, and Byron Shire Council played a more active role in issuing stop work orders and advocating to the state government even after approvals went through.

This is the context of the current Save Wallum campaign in Brunswick Heads. Throughout Australia, 999 times out of 1000, communities give up protesting against environmentally destructive residential developments once they’re approved. And even on the extremely rare occasions where people do continue to engage in direct, disruptive protest, it doesn’t last very long.

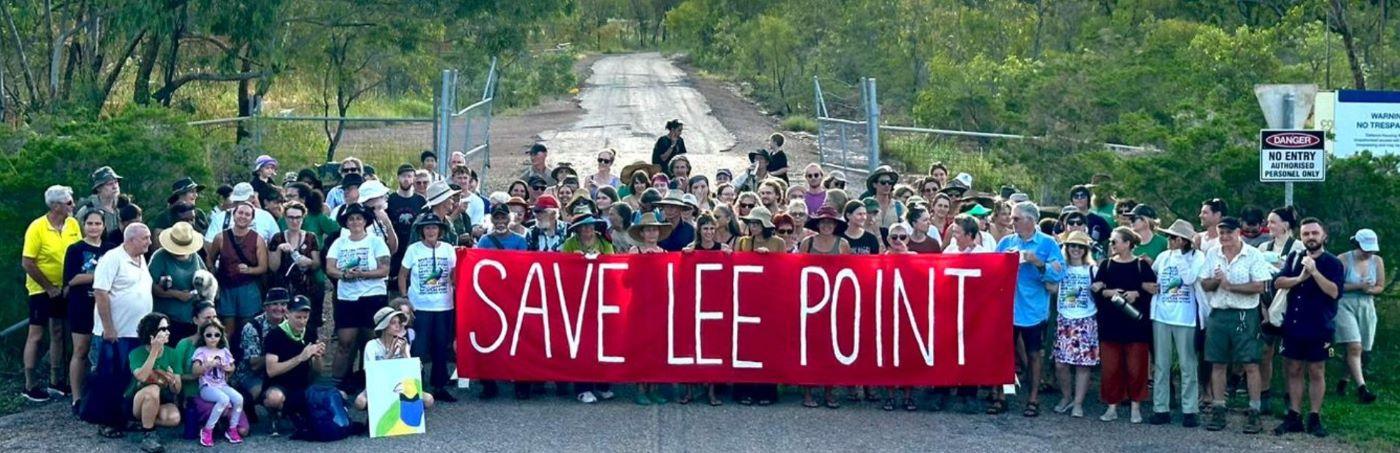

At the time of writing, one other similar outpost of resistance is still going strong up in the Northern Territory. The Save Lee Point campaign has been fighting a much larger proposal by Defense Housing Australia (a government-controlled body) to clear approximately 100 hectares of bushland at Binybara/Lee Point, immediately north of Darwin, for 740 residential lots, most of which it intends to sell off to the private sector. Despite clear opposition from Larrakia landowners and the Northern Land Council, Darwin residents have not been able to stop tree-clearing altogether, but continue to use blockades and lock-ons alongside other tactics to delay development, while pressuring the federal government to halt the project.

The significance of these two ongoing campaigns should be obvious to anyone who thinks about it.

“It’s already been approved” has long functioned to suck the wind out of community campaigns. To continue to fight even after a development receives the go-ahead is an act of bloody-minded utopian rebellion.

This isn’t just about planning and development, it’s about democracy – about communities resisting decisions they don’t like, even when governments and private companies collaborate to override the long-term public interest.

Unlike many parts of the world, where communities themselves have the power and capacity to build their own housing, construction in Australia is a huge, specialised, lucrative industry, with most developers prioritising short-term profit ahead of the long-term interests of future residents. The dominant model – exemplified by developments like Wallum – is systematically failing to deliver genuinely affordable housing, while also destroying the environment and forcing more residents into lifestyles where they have to drive on a daily basis. Approving such projects drives up land values, while crowding out alternative, more sustainable housing models.

It’s not just that developments like Wallum and Lee Point aren’t improving the supply of affordable housing. They actually make it less likely that urgently-needed public housing and non-profit community housing will be delivered, because they soak up construction materials and labour power, and crowd out alternative housing models (small-footprint tiny house ecovillages, medium-density co-housing etc.) that might otherwise be more viable.

If either of these campaigns succeeds (particularly Save Wallum, given that it opposes a private development rather than a government project) they’ll become a spark of optimism and hope for a hundred other campaigns across the country.

They’ll also send shivers down the necks of every residential developer and property financier who’s contemplating a project that the community objects to.

The stories we tell matter

For decades now, the property industry could take it for granted that once they’d secured their approvals from a council or state government, they could confidently push ahead with hiring construction contractors and advertising blocks for off-the-plan sale. No matter how many thousands of opposing submissions a development application attracted, it was virtually unstoppable once approved. This meant developers didn’t have to put much effort into convincing a community that their project’s overall benefits outweighed any negative impacts.

A well-publicised, successful campaign could destabilise those old certainties. And with an onsite occupation now into its sixth month and counting, Save Wallum certainly feels like it could succeed.

"Wallum is not affordable homes. This is high-end luxury homes in an incredibly inappropriate place with critically endangered species that will change the hydrology of an area that was already prone to flooding."

– Michelle Lowe, Greens candidate for Byron Shire Council

The wider cultural and political impact of campaigns like Save Wallum depends a lot on what stories we collectively decide to tell about them.

Victory in Brunswick Heads could be narrated by the political establishment as an isolated campaign against a uniquely bad proposal, where one arrogant developer pushed the envelope too far – proof that actually the planning system is still able to protect the most important native habitats.

Or maybe it’ll be dismissed as Northern Rivers exceptionalism – the sort of thing that happens in Byron Shire Greens heartland, but nowhere else.

Alternatively, the campaign could be characterised as the radical spear-tip of a far broader movement calling for more democratic and sustainable approaches to planning and development, serving as an inspiring reminder that communities are still capable of standing up to developer greed, and that if Brunswick Heads can do this, other towns and neighbourhoods can too.

It would almost be more powerful – politically speaking – if Save Wallum wins purely on the basis of the direct action campaign's ground strength. This is essentially what happened with the 2014 Bentley Blockade movement against coal seam gas mining. All avenues for legal challenge had been exhausted, but the sheer weight of numbers of people who were willing to refuse police directions and physically block site access forced the government to call off the police and intervene to suspend Metgasco's exploration licence.

Maybe the damaging optics of potentially arresting hundreds upon hundreds of determined residents will prompt federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek to intervene at Brunswick Heads, or force the NSW government to step in and negotiate buying back the site from the developer. But even if the final victory comes through the courts, it will still constitute a huge win for grassroots community power. That's not just because of how much volunteer work has gone into local fundraising for the court challenge, but because the community blockade successfully held the bulldozers at bay for over five months before the July injunction came through, helping to buy enough time and collect enough evidence to mount the court actions.

If Labor ministers do eventually intervene and say shit like "We've listened to the community and acted accordingly" it will be important to remind the broader public that the Save Wallum direct action campaign forced the politicians to listen, and that volunteers should not have had to protest for months just to get the political establishment to respect the community's wishes.

This bring us to one of the most interesting aspects of the Save Wallum struggle – the extent to which local councillors (and other political representatives) do or don't get co-opted by the property industry and the broader political system.

The Byron Shire councillor quandary: Reform or rebellion?

"Just because it's the law, doesn't mean it's right or just."– Michelle Lowe, Greens candidate for Byron Shire Council

With NSW local government elections fast approaching in September, Wallum is shaping up as a key issue for Byron Shire voters. Greens councillors and candidates are firmly opposed to the development, whereas the reasonably-progressive independent Mayor Michael Lyon (a former Greens member) voted to support the subdivision application when it came before the council, essentially saying he didn't have a choice.

A few weeks ago, I interviewed Mayor Lyon, and Deputy Mayor (and Greens councillor) Sarah Ndiaye. I also had a shorter chat with Bundjalung woman Michelle Lowe – a local high school teacher and another of the Greens' candidates for Byron Shire Council (full recordings of these interviews are embedded at the bottom of this story, so you can listen for yourself to see if you think I've represented people's positions fairly).

Michael Lyon was elected as a local councillor on the Greens ticket in 2016. He left the party to sit as an independent, and became Byron's mayor about three years ago. "When I joined [the Greens] it was all about the environment – riparian zones, regeneration... When I got onto council, the issue on the ground was housing, and that needed to be the focus. So that's what I've spent most of my time on council dealing with, is the housing crisis."

If I'm honest, I think Michael will struggle to retain the mayoralty at the September election, and there are recent signals he might not even recontest. This makes reflecting on his approach – and what a future Greens mayor might do differently – even more important.

While a few local Greens supporters I've chatted to see Michael as having 'sold out' out to private developers, his values and strategic approach don't differ dramatically from other Greens councillors and MPs around Australia who've ended up wielding some degree of administrative power. He supports more government investment in public housing, supports uplift taxes so that property investors who benefit from upzoning contribute towards local infrastructure costs, and he is particularly critical of the profit-driven conversion of residential homes into short-term accommodation.

However he seems to genuinely believe he had no choice but to approve the Wallum development subdivision application.

"It's a difficult one because yes the protesters are right – it is valuable habitat, it is worthy of protection, but the legal system is set up to protect development rights," Michael told me. "For council to then undertake an exercise of fighting a losing battle and wasting potentially hundreds of thousands on a losing battle to, in my view, virtue signal, it put us in a difficult situation."

Basically, Michael's stated view is that the NSW government had already approved the overarching Wallum development proposal, so if Byron Shire Council withheld the specific subdivision approval (which it granted in February this year), the developers would have challenged that decision in court and won anyway. Other mayors – both in Byron and in Greens-led councils further south – have taken similar strategic approaches over the years.

The local council landscape in Byron Shire exemplifies a deeper challenge that councillors (of all political affiliations) across the country frequently grapple with...

State governments have broad powers to overturn council decisions about individual development applications. And in many parts of Australia – Queensland in particular – smaller shires have been forcibly amalgamated into much larger local government entities, making it easier for big business to lobby and manipulate key decision-makers. Even federal politicians are now talking about nationwide housing policy changes that could discourage or prevent local councils from blocking unsustainable development projects. And there's always the distant (but tangible) threat that the property industry might convince state politicians to dismiss a group of overly-obstructive councillors and place their council into administration.

So while I don't agree with his approach, I can understand why Michael is worried that if he pushes back too strongly against unpopular development projects, he might lose what little power he has to shape broader planning and development outcomes across the shire.

On the other side of the coin, the Greens are unequivocally backing the Save Wallum protests. "There are really sensible places to put houses, and those sensible places are not on wetlands... not bordering on national parks," Michelle Lowe told me.

Deputy Mayor Sarah Ndiaye (who will be the Greens candidate for mayor at the 14 September election) seems much less concerned than Mayor Lyon about the possibility of the state government coming in over the top. "I think the mayor is perhaps leaning on that threat in a way that we don't need to. We've been banging at the door of the planning office for the last eight years... It would be hard for any state government to say we've been 'anti-development' because we haven't."

Sarah rightly points out that over the years, Byron Shire Council has been advocating for various alternative models to create more housing that's genuinely affordable and sustainable (and to protect existing homes from Airbnb conversion), but was often blocked by a state government that's wedded to cookie-cutter development models which maximise profits for the private sector.

"I've stuck my neck out time and time again to increase density in certain areas, to allow for developments to go ahead," she said. "But I don't think building in ecologically highly sensitive areas on floodplains that are close to waterways is the way to go."

She hopes the council's history of supporting certain kinds of development (rather than flat-out objecting to all new development) means Byron Shire will have more credibility when it does push back against especially problematic projects like Wallum.

But the broader question remains unanswered... Sometimes mayors and councillors have no lawful mechanisms left available to stop a controversial project, and the best they can offer the community is a partially improved compromise that still permits significant harm of one kind or another, and leaves many residents wondering if their elected reps have just sold them out.

This is the pathway to co-option that generations of progressive councillors have found themselves on, and which more Greens parliamentarians at higher levels of government are also increasingly grappling with. This hasn't happened just in Byron, but also in other jurisdictions where the Greens have held or shared majority control over a local council or even territory legislature (see e.g. the ACT Greens, and some of the inner-Melbourne councils).

The more power you hold, the more pressure you come under to help maintain the status quo rather than transforming it. This pressure takes many forms, from ministerial threats to strip away your council's limited planning powers, to industry warnings that you'll 'destroy jobs' or increase housing costs, to councillor conduct complaints frameworks that in some contexts have the power to fine you for misconduct if you're supporting 'unlawful' protest actions.

Mayors and councillors definitely don't wield unfettered dictatorial power, and are frequently wedged between their community's aspirations and the conflicting agenda of higher levels of government. The most common response to this quandary seems to be to lobby and negotiate for minor reforms and compromises, then tell the community you did the best you could but your hands were tied.

In the long run, this form of leadership can be disempowering and demobilising for local communities... You can tell residents you're on their side and want the same things as them. But when push comes to shovel excavator, if you're not willing to lead by example and use your privileged position to support and participate in direct action, you're potentially still legitimising the broader system you're elected into, even as you criticise some of its specific outcomes.

As a lone Greens councillor in Brisbane, I tried to take a different approach – don't settle for pissweak compromises, demand more from the establishment, and actively participate in community protests that directly challenge outcomes we're not happy with. But of course, that was an easier, more straightforward position to take on a council controlled by the Liberal National Party – I never had the power/responsibility of actually running a council administration.

If Byron's current mayor Michael Lyons can be said to have exemplified the reformist, incrementalist approach, other mayors and councillors who seek deeper transformation of society could still explore alternative, revolutionary approaches to elected leadership. We've seen glimpses of this in the past, such as when former Greens councillor Richard Staples climbed onto that bulldozer to protect Paterson Hill.

If the community you represent broadly agrees on a particular vision for the future, and what kinds of changes it does and doesn't support, is it good enough to merely complain about it when state or federal governments override the community's will? Or do you have an obligation to do what mayors and local leaders in other parts of the world sometimes resort to – leading and co-organising broader rebellions and uprisings against the destructive and oppressive actions of governments and corporations?

Michelle Lowe was pretty clear that if elected, she'll use her platform to support protests for deeper change. "You have to stand up because it's only through collective action you actually change laws."

But I still wonder how a newly elected Greens mayor and councillors will respond in practice when the full co-opting force of the political establishment bears down on them.

I guess that remains to be seen.

Note: The following interviews have been edited slightly to remove interruptions and longer pauses.

Thanks so much for checking out this piece. I hope readers appreciate having access to the full interviews as well. Pulling articles like this together takes a lot of time and research. As far as I'm aware, this article includes the only comprehensive nationwide overview of recent blockades against residential development projects, and will hopefully serve as a useful reference point for other campaigns. If you enjoyed this article, and you value information like this being publicly available, please support my writing by signing up for a $1/week subscription.

And don't forget to share this article online with friends!

Member discussion