Why Queensland's 'Olympic Games Infrastructure Review' is skewed and biased

Governments often initiate 'independent' reviews as public relations exercises to minimise the political fallout of backflips on previous positions.

Prior to the 2024 state election, the Liberal National Party were very critical of how much money Queensland Labor's proposed Olympic venues were going to cost. As the projected costs of a new Gabba stadium climbed past $3 billion, the Liberals sought to make a lot of political mileage criticising such high spending – and the lack of a business case for the project — as irresponsible.

Now, after the election, the new LNP government has launched another '100 day review' (Steven Miles already did one of these to try to distance himself from Annastacia Palaszczuk's positions), telling Queenslanders they can 'have their say' on the Olympics.

https://www.instagram.com/reel/DDYa_X9yzWS/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

The government said the review "will be informed by a public submission process (open for a suitable portion of the 100 days)." The public submissions process opened on 10 December (with minimal promotion) and closes on 10 January. Scheduling public submissions periods over the Christmas holidays tells you how little weight the process will give to the concerns of average residents. I'm still going to make a short submission to their review. But I don't believe they actually care very much what everyday Queenslanders think.

In fact, I'm convinced the review is largely a PR exercise to justify the LNP shifting towards supporting new stadiums (after strongly criticising Labor for this), because the terms of reference are skewed towards wasting money on new venues, and the appointed reviewers have strong interests in supporting mega-projects.

Not really very 'independent'

The seven members running the new review are:

- Stephen Conry (chairperson) – National president of the Property Council of Australia from 2019 to 2021, former CEO of commercial real estate giant JLL, chair of private investment company Langdon Capital, and current chair of property investment group Charter Hall

- Jess Caire, executive director of the Property Council of Australia's Queensland division

- Tony Cochrane, co-director of event production company Cochrane Entertainment and former chairman of the Gold Coast Suns AFL team (he also seems to make a bit of money off real estate)

- Jill Davies, an events consultant who seems to be the only one with direct experience running stadiums, and who worked as one of the program managers of the Sydney Olympics

- Jamie Fitzpatrick, managing director of FGH group, a hospitality company that primarily runs restaurants, bars and hotels in Townsville

- Sue Johnson, the former Queensland boss for toll road company Transurban (it's concerning that the only committee member with a transport background doesn't seem to be a strong advocate of public transport)

- Laurence Lancini, founder and executive chairman of property developers Lancini Property Group (his net worth today must be upwards of $200 million)

I'm not necessarily suggesting these people have particularly close ties to the LNP government, although some like Mr Lancini are major political donors to the party. Labor has certainly been running that line, which undermines the perceived legitimacy of the committee's recommendations.

What primarily concerns me is that most of the committee members own investments and work in industries that make a lot of money out of property speculation or event management. They may be independent of the public service hierarchy, but their recommendations will inevitably be shaped by their personal financial interests in rising property values.

In making decisions about Olympic infrastructure, the impact on land values and housing affordability should be a key consideration. The likely displacement of low-income renters was one of my many reasons for opposing an Olympic stadium at the Gabba (Woolloongabba and Kangaroo Point have especially high proportions of renters, so upward pressure on rents and the conversion of rental units into Airbnbs were strong concerns in that part of the city).

Mega-projects often drive up house prices. But Crisafulli's hand-picked committee doesn't include a single member who will be looking out for those of us who want rents and house prices to get cheaper. Several members have property portfolios worth tens of millions of dollars, but there's no-one from the social services or non-profit housing sectors (concerningly, there's also no-one with expertise in urban planning, environmental sustainability or public transport). And the review's terms of reference don't meaningfully counteract the biases built into the committee membership.

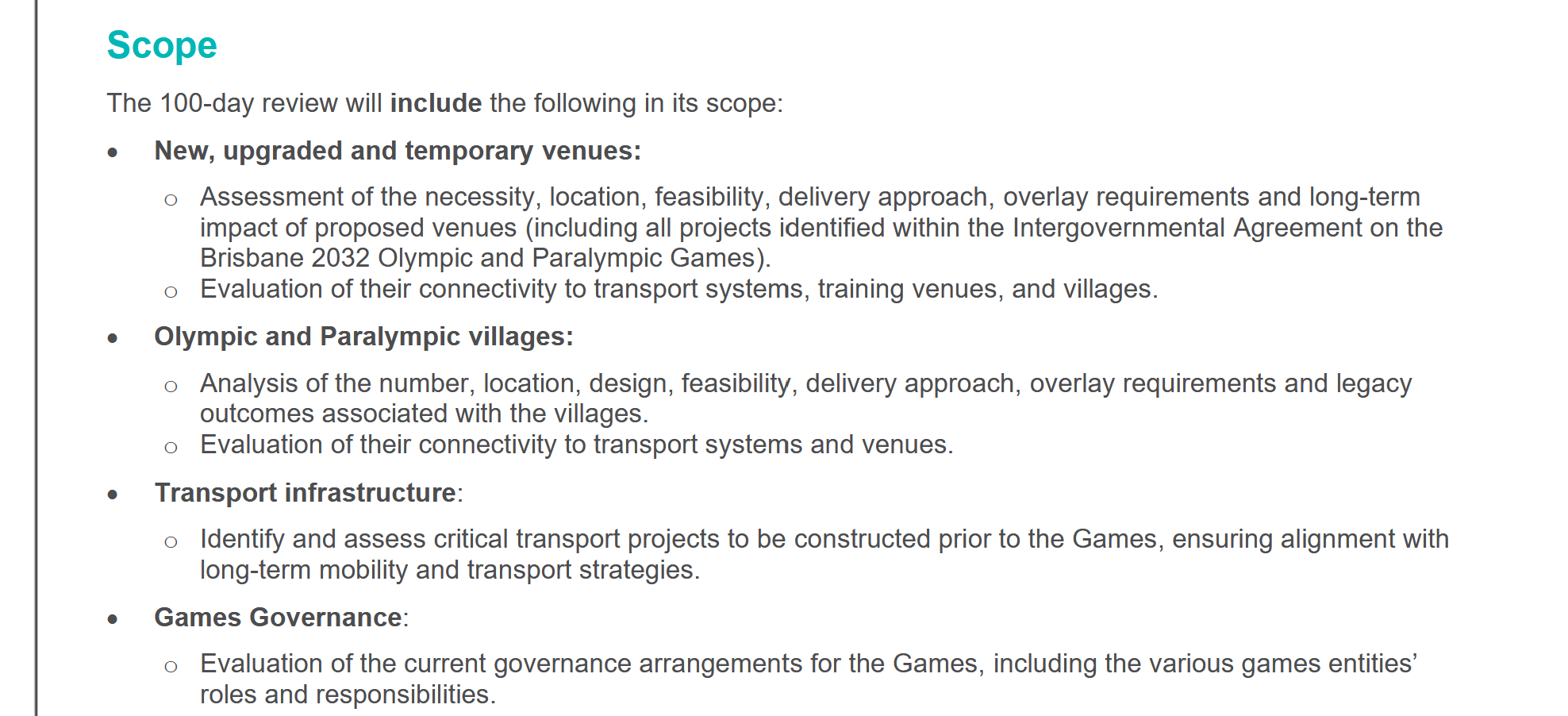

Terms of reference omit key issues and skew the outcomes

While primarily framed as a review of Olympic and Paralympic infrastructure, the terms of reference take a fairly narrow definition of the word 'infrastructure' as only referring to venues, transport facilities and athlete villages. There's no mention of reviewing the location or scale of other costly pieces of Olympics-related infrastructure.

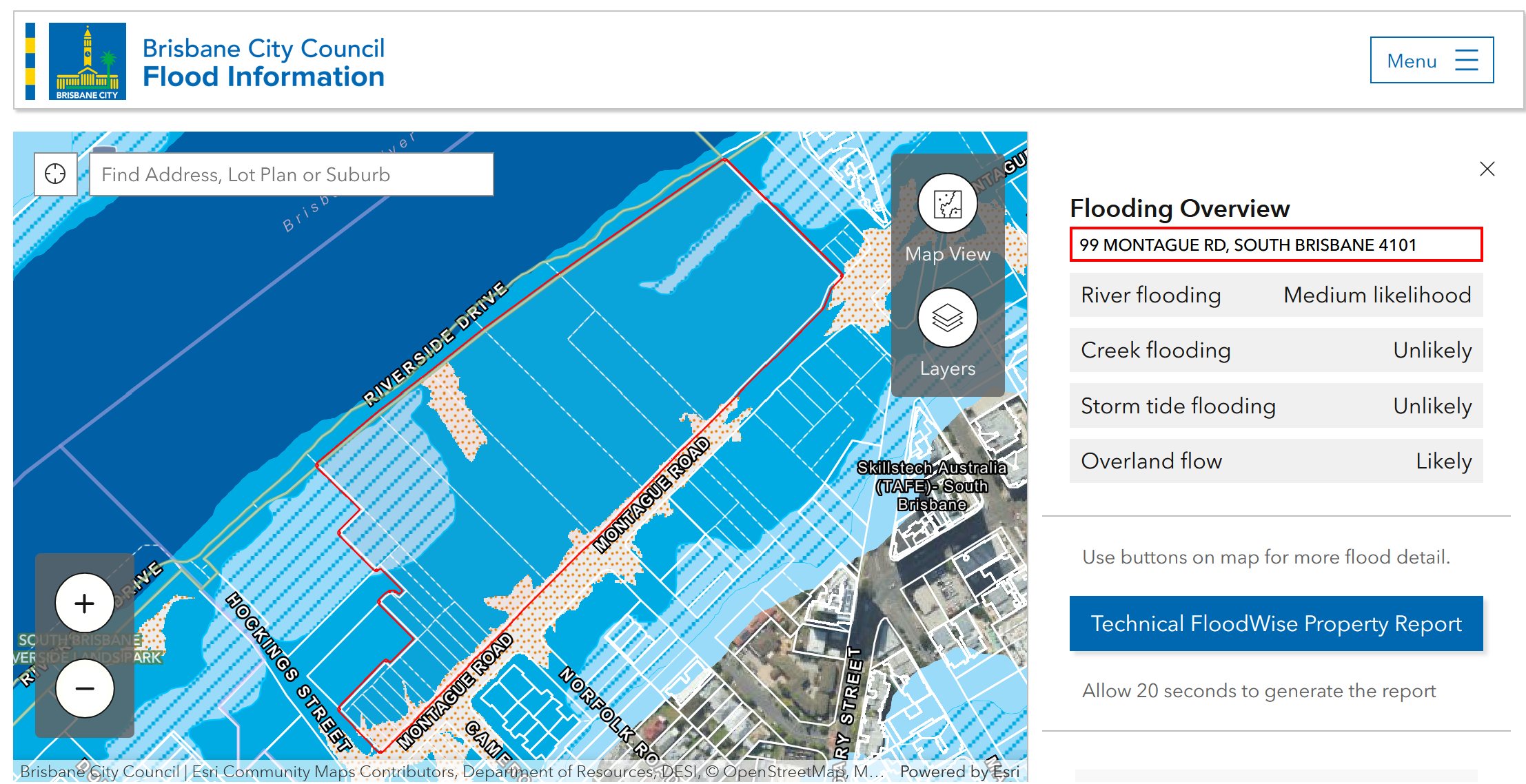

Floodprone broadcast centre

For example, in support of the previous Gabba stadium redevelopment plan, the government proposed a massive broadcast centre along West End's riverfront on a (now publicly-owned) site which has for decades been gazetted in the city plan as future parkland. The government purchased the floodprone site for $165 million in 2022. It plans to hand it over to the IOC to build an International Broadcast Centre for journalists covering the Olympics, denying tens of thousands of local apartments residents access to what would've become at least 7 hectares of public parkland for another decade.

Much of the site flooded to a depth of around 1.5 metres in January 2011 and again in Feburary 2022. So you'd think reconsidering the broadcast centre's location would be a key element of the Olympics infrastructure review, especially if the Gabba isn't going to be used as a major venue. I'm hoping the reviewers will adopt a definition of 'venues' that's broad enough to include the International Broadcast Centre, but the terms of reference don't mention it directly.

Intrinsic bias towards expensive new venues

The document's 'Scope' section says evaluation of venues will include "their connectivity to transport systems, training venues, and villages." This makes me worry that finding sites which already have good mass transit connections will be higher on the priority list than improving public transport infrastructure to connect to existing venues.

Conveniently for those advocating high spending on stadiums, the review terms of reference effectively treat the previous federal-state funding agreement between Scott Morrison and Annastacia Palaszczuk as a de facto venues budget (an 'agreed funding envelope') of $7.1 billion. So it's baking in an assumption that a whopping $7.1 billion will be spent on venues alone, contrary to previous assertions that hosting the Olympics would require minimal new venue infrastructure.

While this funding envelope presumes construction of wasteful white elephant venues, the terms of reference don't specifically rule out use of state government-owned land, or suggest that the value of land should be incorporated into venue cost estimates.

In urban areas, the cost of land should be (and generally is) incorporated into the estimated cost of government projects (this is why rapidly-growing inner-city neighbourhoods often miss out on important infrastructure like public housing, schools, libraries and parks).

If the terms of reference contemplate spending up to $7.1 billion on venues, but that figure doesn't have to include the value of government-owned land that could be used for other things (like housing or parkland), this will bias the review against upgrading existing venues like Carrara Stadium on the Gold Coast or QSAC at Nathan. It will bias the review towards building new venues on government-owned land such as at Barrambin/Victoria Park, because the multi-billion dollar value of that land and the alternative uses it can otherwise be put towards won't be properly considered.

Similarly, framing the review around the $7.1 billion funding envelope for venues will mean less consideration is given to the possibility of minimising spending on venues and maximising investment in public transport infrastructure. For example, options like the Gabba or Barrambin are reasonably well-served by public transport but involve spending a lot of money on stadiums, whereas QSAC at Nathan is currently considered less desirable because it lacks mass transit connectivity. From a long-term legacy perspective, it might make more sense to spend several billion dollars on new heavy rail and light rail connections to Nathan (also benefiting local residents and the neighbouring QEII hospital and Griffith University campus), with less expenditure upgrading the stadium itself. But the terms of reference will tend to discourage this kind of thinking.

No mention of global warming and climate action targets

Brisbane's Olympics bid included an agreement with the IOC that the games would be 'carbon positive' – that is, the overall event would draw down or offset all of its carbon emissions, and even more carbon dioxide on top of that. What kinds of emissions do and don't get included in these calculations is ambiguous, and the very concept of carbon offsets is highly questionable. But at the very least, a 'carbon positive' calculation ought to include the environmental impacts of new venue construction. The embodied energy and resources that go into a new stadium are huge. But the terms of reference don't seem to acknowledge the 'carbon positive' goal at all.

This omission would likely also shape recommendations about transport infrastructure. If the committee doesn't care about carbon emissions, it will inevitably place less value on improvements to public transport.

Lack of consideration about the impacts of climate change will also skew review recommendations. Not only will the flood vulnerability of certain proposed venue sites (e.g. Hamilton) be ignored, but the heat sink value of existing green spaces like Barrambin/Victoria Park will also be under-estimated.

An uncertain future

The reality is that planning for a mega-event in the early 2030s is exceedingly difficult. Geo-political upheavals, rising long-haul air travel costs, big changes in digital sports coverage and the worsening impacts of global warming mean Brisbane 2032 will necessarily be a very different kind of event to recent Olympics (if it's not cancelled altogether).

The compounding uncertainties of new venue construction mean it's far safer and wiser to focus on adapting and reusing existing facilities. Moreover, decision-making structures for the games need to allow far more flexibility to adapt to rapidly changing circumstances.

Unfortunately the terms of reference of this review, and the people leading it, have a far narrower focus. The whole exercise is biased towards building new venues on government-owned land in locations that will put upward pressure on private property values. Unless there's a very strong public pushback, that's most probably what we're going to get.

I write semi-regularly about the future of Brisbane through ecological, anti-colonial and social justice lenses. Right now, I'm one of very few public commentators who's willing to critique the Queensland political establishment's grow-at-all-costs mentality, which denies the true ramifications of global warming and treats rising property values as an unquestionably good thing.

If you value more writing along these lines being available in the public realm, please consider supporting my work by signing up for a paid subscription.

For more on the Olympics, check out this article next:

Member discussion