Buyers/renters beware: Brisbane City Council keeps approving new developments, but Southern Woolloongabba, East Brisbane and Stones Corner will flood more often

The smell of flood mud stays with you.

It's different to the normal, fainter mud odour you encounter walking along mangrove-lined riverbanks.

It's earthier... but also unearthly – a distinctly non-urban scent.

Even if I've been away from home for a few days, and nothing much looks out of place, I can still tell from that smell when rushing waters from a heavy storm have recently scoured the deeper layers of the creek bed, resurrecting the older, greyish silt from below.

It's a reminder of how quickly the neighbourhood can change – and that we shouldn't get too complacent...

After the March floods of 2022, I had a (rare) one-on-one meeting with Brisbane's Liberal National Party mayor, Adrian Schrinner.

I showed him some of his own council's City Plan maps with the 'flood planning overlay' turned on. I showed him photos and video clips of devastated streets and homes, and talked to him about how even relatively new buildings designed after the city's 2011 floods – supposedly with higher flood resilience standards in mind – had been severely impacted by the 2022 disaster (you can get a feel of these issues by reading my April 2022 submission to the government's flood response review).

I drew his attention to the research – research which many other people have showed him in the past – that clearly outlines the increased risk of future severe floods due to global warming. I pointed out that the council was now dealing with the legacy of two centuries of poor planning, and that we had an obligation not to create a bigger mess for future council administrations. I implored him (not for the first time) to implement major changes to Brisbane's city planning rules to restrict development in low-lying areas.

I already had a low opinion of the LNP's reckless attitude to global warming. But his response still shocked me.

Many parts of our city had just experienced the heaviest three days of rainfall in living memory – over 1100mm in under 72 hours. Records had been broken all over the place, and all the science was telling us that events like this will become much more common in future. But Lord Schrinner and his colleagues had decided that no changes needed to be made to the development rules for most sites across Brisbane.

The power of the property development lobby, outlined so clearly in historian Margaret Cook's excellent book, A River with a City Problem: A History of Brisbane Floods, is as strong as ever.

Since 2022, the council has made a few minor tweaks to its citywide mapping of which properties are considered flood-vulnerable. But two overarching problems remain:

- the lists and maps of which blocks are deemed at risk don't fully account for likely future increases in both flood frequency and severity due to global warming

- even on sites which are identified as having higher flood risks, the city plan still allows intensive development, merely requiring that residential floor levels and key infrastructure be raised slightly higher off the ground

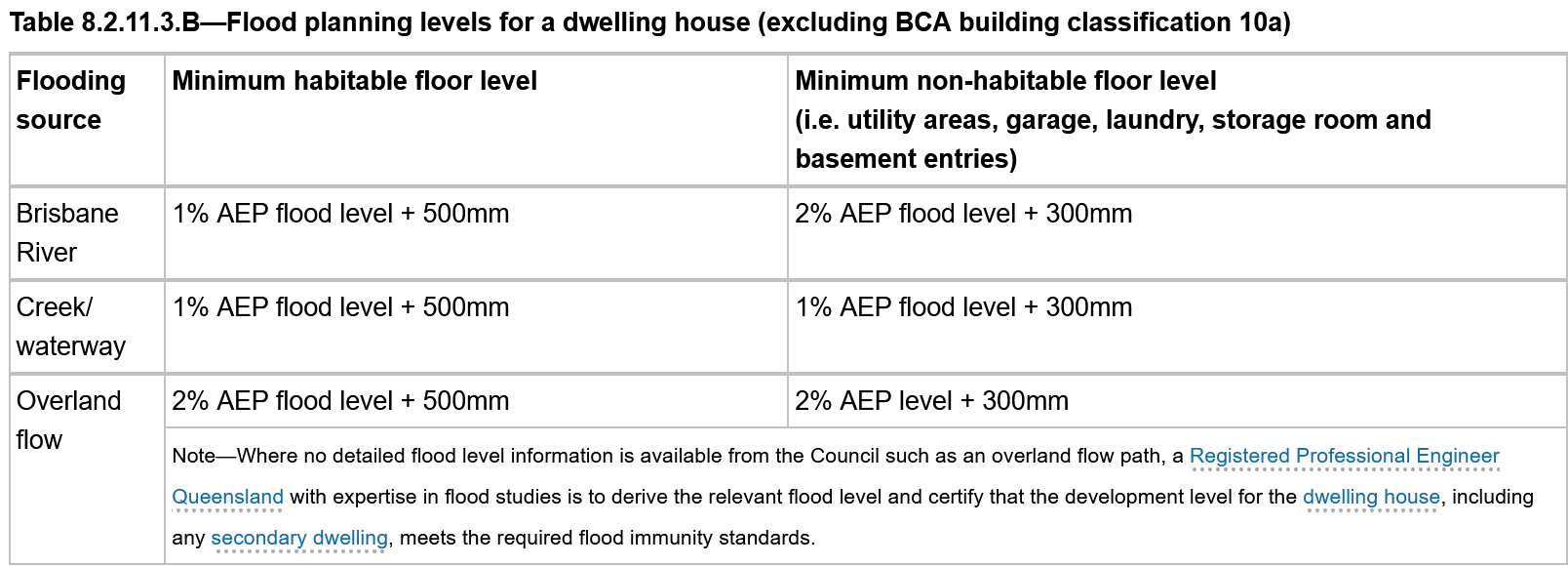

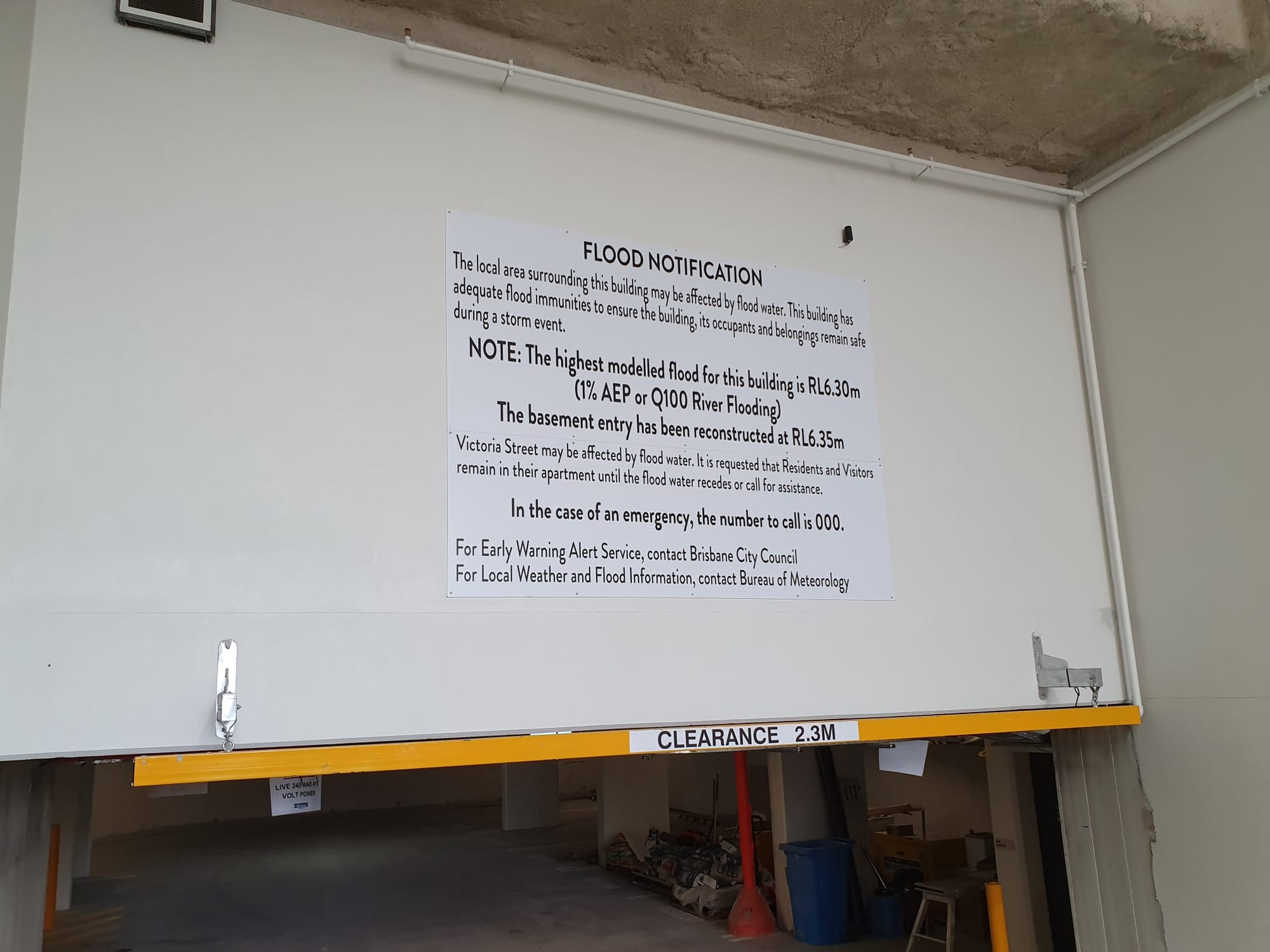

Today, a lot of the council's design requirements are based around the level of a so-called '1 in 100 years' flood – a flood with an Annual Exceedance Probability ('AEP') of 1%. For free-standing houses and residential apartments, the council basically looks at a block and says "How high is the water likely to get on this particular site during a 1 in 100 years flood?" and requires the developer to ensure that residential floor levels are at least 50 centimetres higher than that. Other important features like basement carpark entrances don't even have the 50 centimetre clearance requirements.

This has been a fairly standard approach around Australia since the 1980s (historically, communities were more cautious, making sure to build above the highest flood level on record). Generally speaking, even if your new, council-approved house or ground-level apartment has supposedly been constructed "above the flood levels," if the floodwaters are just 50 centimetres higher than a '1 in 100 years' flood, you might still go under.

And as we should all have realised by now, just because a certain flood level is described as having a '1 in 100 years' probability, doesn't necessarily mean the water will only get that high once a century.

Kulpurum/Norman Creek flood modelling is outdated

It's important to emphasise that a lot of rigorous work goes into flood planning and modelling. Brisbane City Council's hydrologists and engineers test the accuracy of their theoretical models against real-world events, refining and updating over time. And they conduct site visits to diligently measure the dimensions of individual creek culverts and drainage channels so they can estimate as accurately as possible how much water can flow through the landscape under different conditions.

But even the most detailed modelling can never fully account for the complexities of an ever-changing urban environment. A few thoughtlessly-placed skip bins might change how much water flows down a certain drain compared to how much flows overland. A poorly-maintained backflow prevention device might fail to open or close at the right time if it's clogged with debris. And of course, new developments can change where water flows and how much rain is soaked into the ground.

One of the biggest variables is how much rain you assume could fall in the first place.

This bring us to Kulpurum/Norman Creek – one of Brisbane's most urbanised and heavily developed creek corridors. I've gotten to know this waterway pretty well through volunteering on various local conservation projects, my 7 years as a city councillor representing the inner-south side, and living on a houseboat that's often moored on it.

The waterway's longest tributaries start their journey in Toohey Forest and the slopes of Mt Gravatt and Tarragindi. They wind through Holland Park, Greenslopes, Stones Corner and Coorparoo (whose name is a variation of 'Kulpurum' – an Aboriginal word for the creek and the wider area), merging with other creeks such as Kingfisher Creek, which drains much of Woolloongabba.

Flood planning for creeks is a little different from bigger catchments like the river. It's not so much a question of how much rain falls in total over a couple of days, but the duration and exact location of the heaviest falls.

You can find several publicly available flood studies, plans and design investigations relating specifically to Kulpurum online. Flood studies inform the predicted flood levels in the council's Flood Awareness Map, and the City Plan Flood Overlay Code (which sets out relevant development rules).

In the last few years, some site-specific flood investigations have been carried out for certain parts of the Kulpurum/Norman Creek catchment, such as those which informed the design of the Hanlon Park rejuvenation.

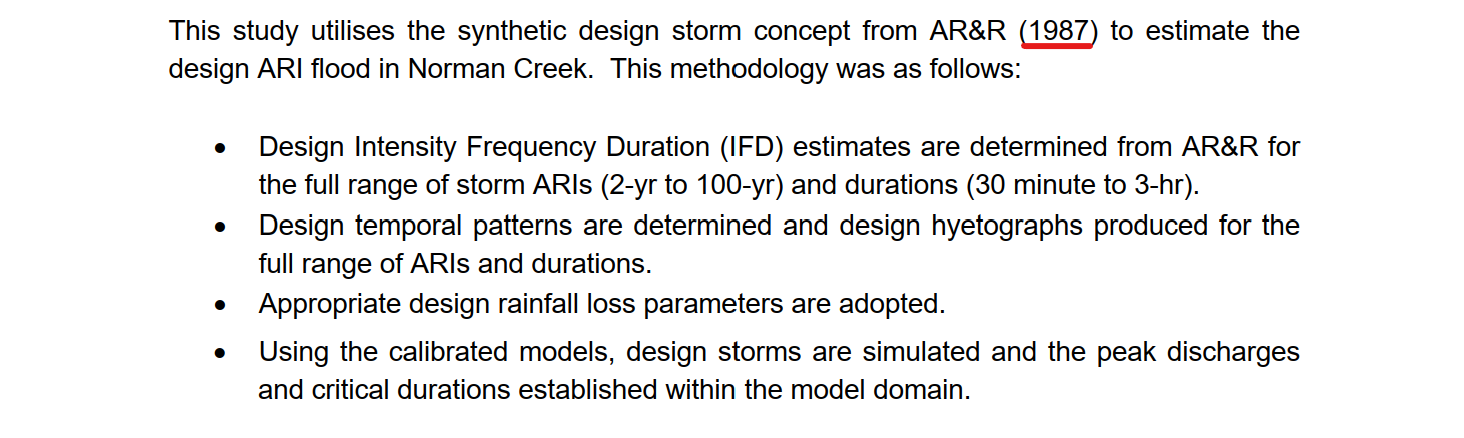

But the Norman Creek Flood Study (which is dated July 2014 but was actually undertaken in 2013) is still the document that serves as the basis for the council's Flood Awareness Map and Flood Overlay Code for the Kulpurum catchment. And get this: the 2013 Norman Creek Flood Study was based on the 1987 edition of the Australian Rainfall & Runoff Guide ('AR&R').

The actual modelling methodologies used in the study are more recent – it's only the baseline estimates for the likelihood of heavy rain events of different durations and intensities that are perhaps out of date.

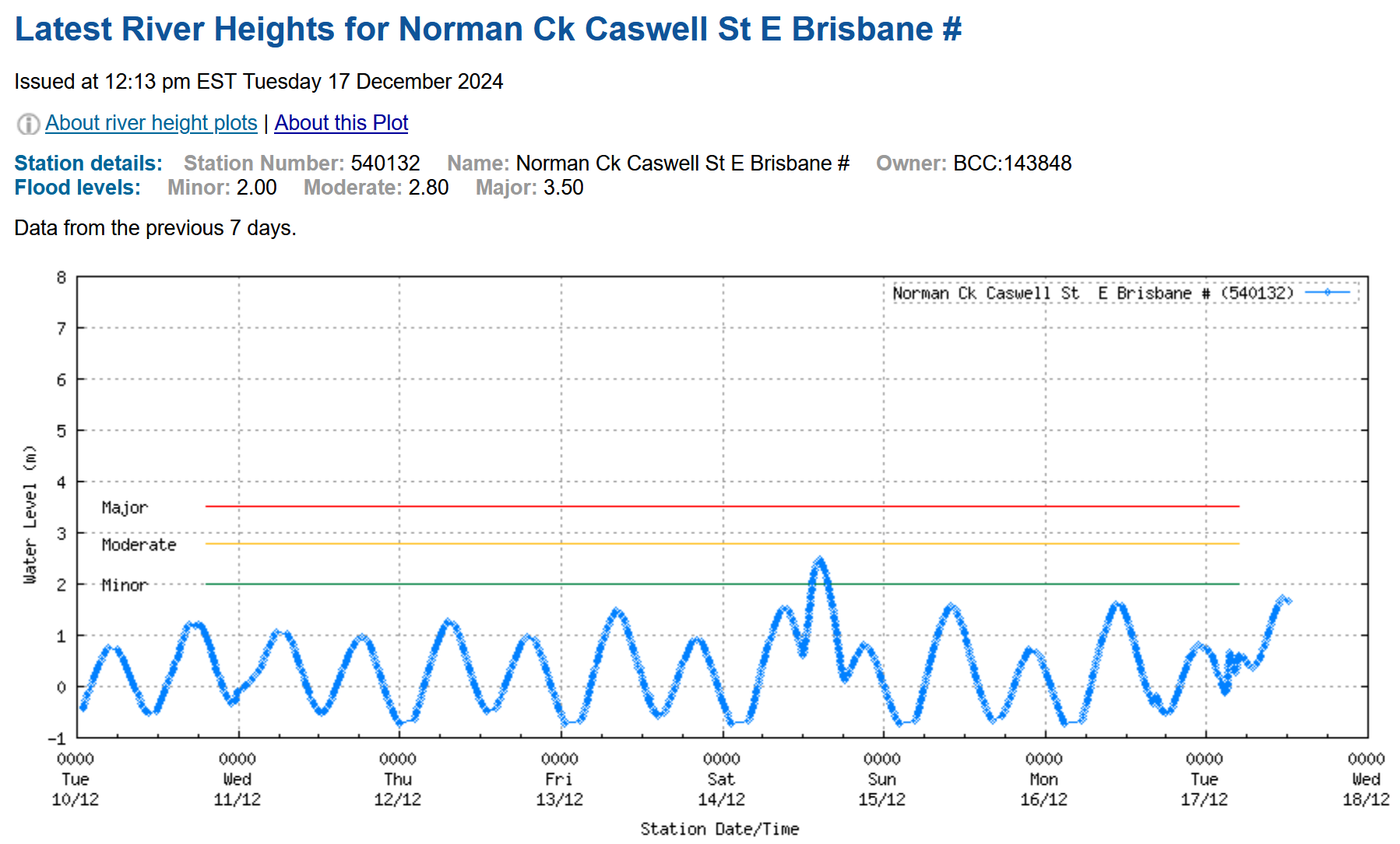

Council's mapping (based on the 2013 Norman Creek Flood Study) suggests the 2 metre 'Minor' flood level has an AEP of about 18% – just under what would be described as a '1 in 5 years' flood. In December 2024 alone, Norman Creek's lower reach – downstream of the Caswell Street gauge – has climbed to the 'Minor' flood level at least three times. It reached that level a couple of times last summer too. That's a lot more frequent than 'once in five years.'

The AR&R guide was finally updated in 2016, again in 2019, and just recently in 2024. With multiple minor and major floods affecting the catchment since the last Norman Creek flood study in 2013, it's definitely high time for a new one.

Predicting the likelihood of future extreme weather is very difficult, with worsening global warming introducing greater uncertainty. But the science does suggest that severe rainfall events – atmospheric rivers, super-cells etc. – could become more common within the Norman Creek catchment – even as long-term average annual rainfalls drop, and our region becomes hotter and drier overall.

One 'super cell' could cause a lot of grief

Norman Creek is a relatively small, heavily built-up urban catchment. In larger catchments (e.g. Maiwar – the entire Brisbane River system), the effects of isolated, short-duration bursts of heavy rain are more easily absorbed. Whereas for the Kulpurum waterways, if Greenslopes and Holland Park West get a sharp burst of really intense rain for an hour or two, water levels can rise very quickly.

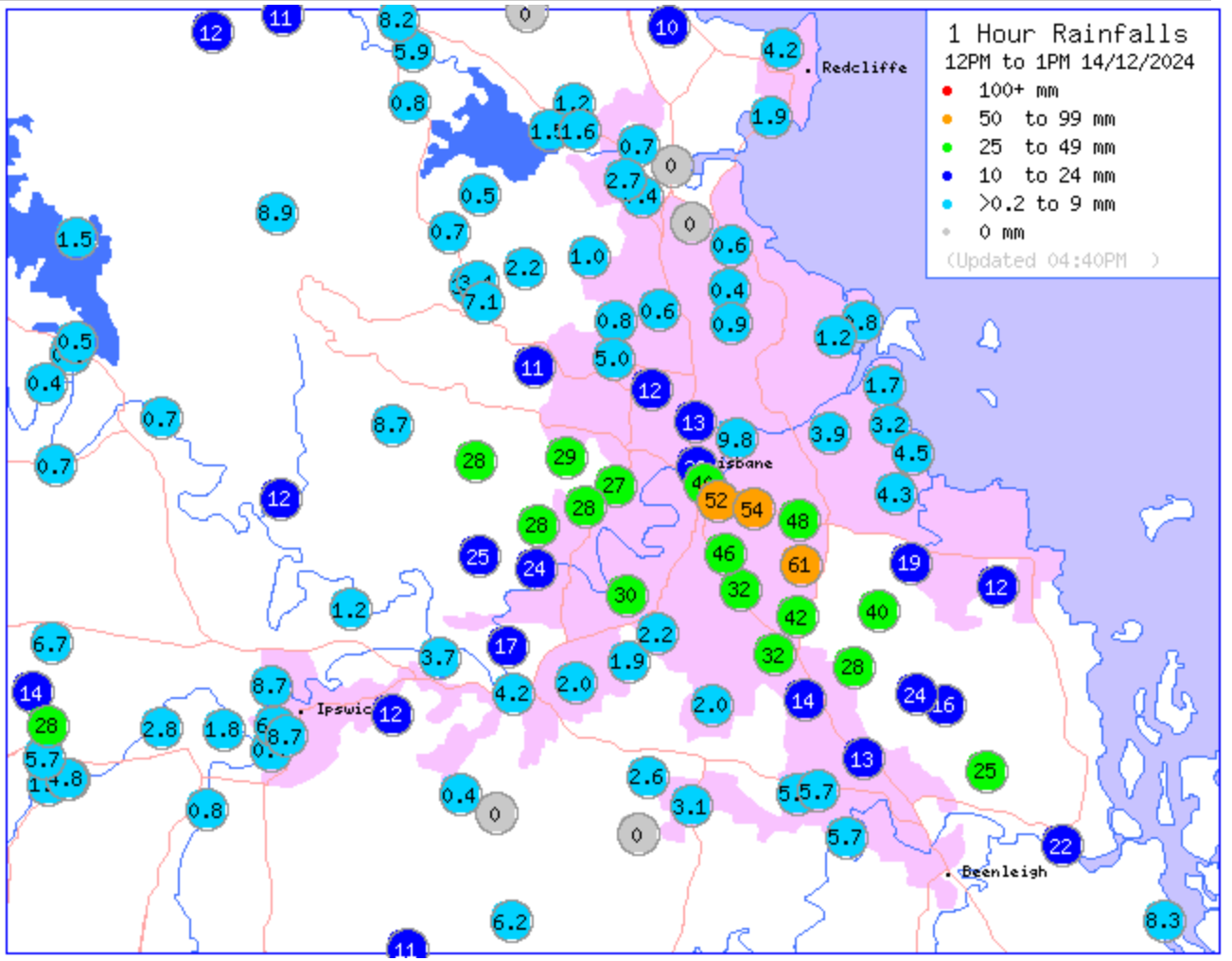

The graph shows the height of Norman Creek at East Brisbane over the past week, cycling up and down with the tides - you can see how on 14 December, a lunchtime burst of 40 to 60mm of rain within an hour was enough to push the creek over its 'Minor' flood level even at low tide

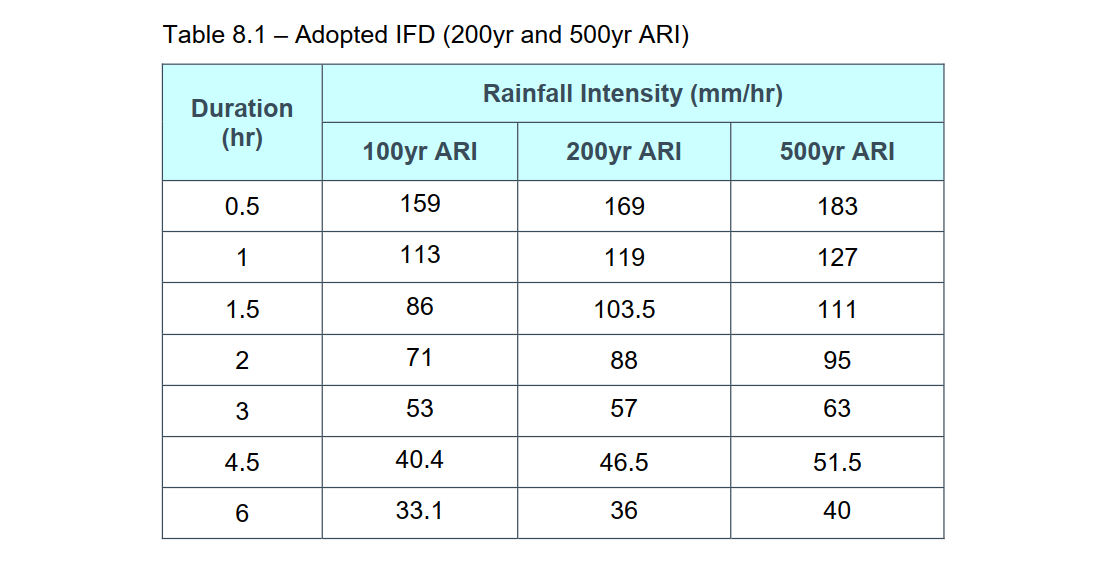

The 2013 Norman Creek Flood Study suggests that 53mm of rain per hour, for three hours, across the whole catchment, would be enough to push waters up to what they call the '1 in 100 years' flood level.

And if the whole creek catchment – from Mt Gravatt through to Coorparoo and Stones Corner – copped a burst exceeding 127mm within one hour, the report says Kulpurum could climb to its '1 in 500 years' flood level, in which case even the Broadway Hotel site at the corner of Logan Rd and Wellington Rd could go underwater.

Remember: the council is still allowing developers to build new bedrooms that are only half a metre above the 1 in 100 year level. And a lot of existing properties are much lower than that.

In the past month alone, several South-East Queensland locations have come close to receiving 50mm per hour for three hours.

If the amount of rain which has recently fallen in some parts of north Brisbane happened to fall in the Norman Creek catchment at the same time as the tide was rising, we could easily see repeats of 2011 or 2022 flood levels in East Brisbane and Buranda, even while the rest of the city remained relatively unaffected. This could happen overnight, in just a few hours, with no time for any government agencies to text warnings to residents – a risky situation for anyone sleeping at ground level.

I don't want to exaggerate risks or come across as too alarmist. I should emphasise that most years, for most days of the year, the creek will not flood (the bigger long-term climate change risk for Woolloongabba is arguably severe, prolonged heat waves).

But rather than focusing only on the possibility of these 'extreme' flood events in the Norman Creek catchment, we also need to consider the cumulative impacts of more frequent, lower-level flooding.

Death by a thousand drops

I know dozens of people living in the Norman Creek catchment who've experienced low-level flooding of their yards, or even the ground floor of their houses, multiple times in the past month alone. This isn't new. Residents of the Deshon Street/Flower Street/Sword Street neighbourhood have experienced flooding of their properties for decades.

But the combined effects of more development further upstream (leaving less green space to soak up stormwater) and more frequent instances of heavy rainfall (due to global warming) mean that nowadays, Kulpurum (along with its tributary Kingfisher Creek) bursts its banks and rises up through stormwater drains fairly often – sometimes five or six times each summer.

Even when low-level floods don't lead to water inside people's houses, they still cause a social and economic impact – more time spent cleaning up yards and driveways, roads cut, garbage collection services and bus services cancelled, sports ovals out of action etc. If water gets into the basement carpark of a newer apartment, its elevator shafts, fire escapes and electrical infrastructure can also be damaged. Cars parked on the street can flood before residents in the shopping centre even realise it's raining. People miss work. Kids miss school. Small businesses lose a day of trade.

The costs to the council add up too – cleaning flooded parks (particularly when there are sewage cross-contamination risks) is a significant undertaking, especially if infrastructure like toilet blocks, public lighting and outdoor barbeques is damaged.

But some of the biggest costs are road-related. More frequent flooding and heavy rain means more potholes and degraded road surfaces.

When I was a councillor, Brisbane City Council averaged $90 million per year on road resurfacing, and even that wasn't keeping up with the maintenance needs of an ever-expanding road network.

After the 2022 floods, the council had to allocate an extra $39.7 million (on top of the usual $90 million for that year) towards resurfacing. The LNP has now stopped publishing dollar figures in its annual budget (so much for transparency), but the additional resurfacing and pothole patching due to low-level flooding will be costing the council millions of dollars per year across the city, and probably a couple million per year in the Norman Creek catchment alone.

@jonnosri We've got to stop approving new development on land that's vulnerable to flooding and recognise that in some areas, the cost of maintaining basic infrastructure will skyrocket due to sea level rise, even when we're NOT impacted by severe storms. #globalwarming #fossilfuels ♬ original sound - Jonathan Sriranganathan

The stress and disruption of a major flood is manageable if you know it's only likely to happen once or twice in a lifetime. But when you have to be on alert every wet season, and can't even go away for a summer holiday without first moving all your furniture upstairs, it starts to wear you down.

Insurance premiums are also rising for public entities, businesses and private residences alike.

No-one in power seems to be talking about this. But if minor floods become too frequent, the cumulative impacts of the creek bursting its bank once or twice a month each summer might start to resemble the effects of a major flood in terms of the community's experiences and costs.

What the heck is the council thinking?

All this brings us back to Brisbane City Council's bloody-minded lunacy in continuing to approve new developments on sites within the Kulpurum/Norman Creek catchment that are highly vulnerable to flooding.

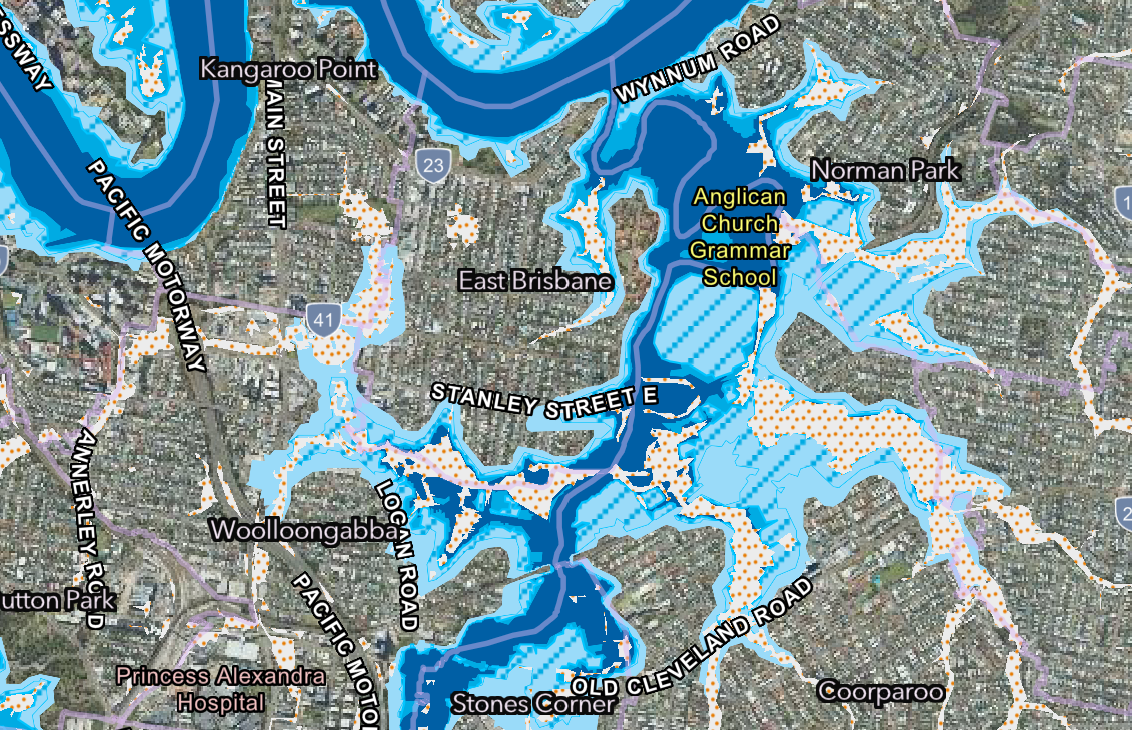

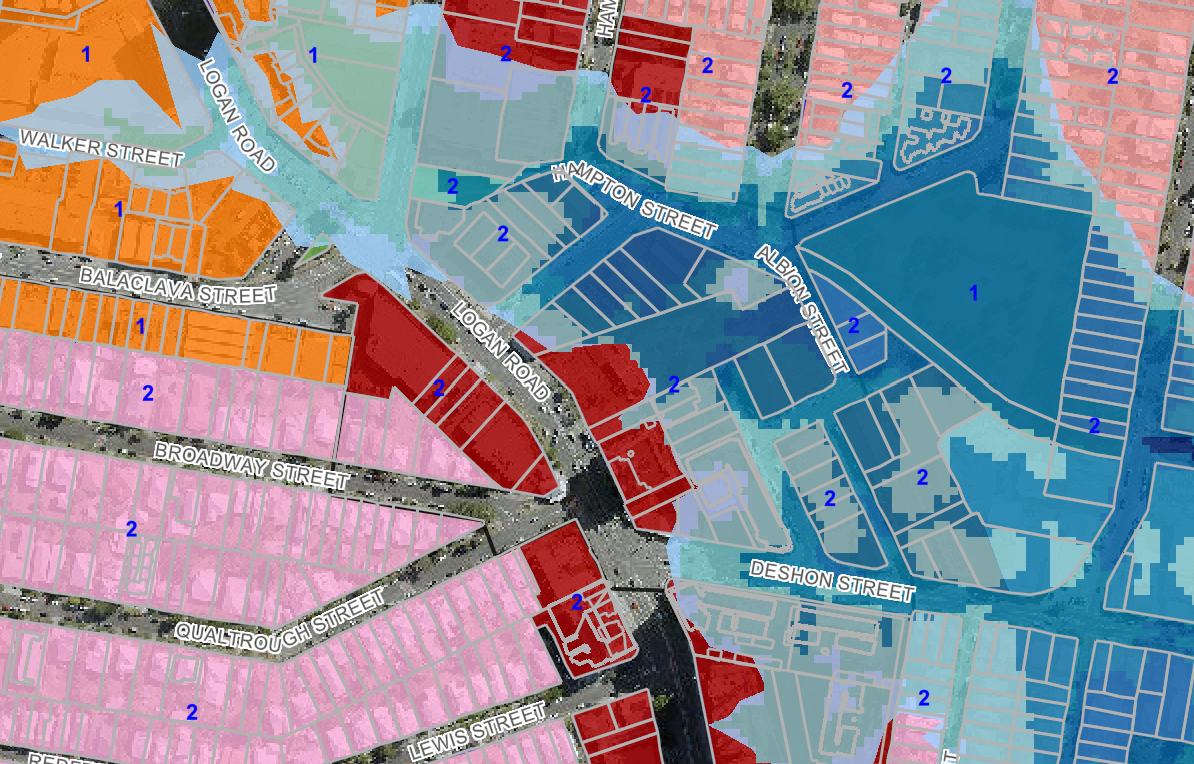

Right now, several hundred homes would experience flooding of inhabited areas if Norman Creek rose to the 0.5% AEP ('1 in 200 years') level, and about a thousand more would experience flooding of yards, driveways and streets where cars are regularly parked. Even more properties are at risk of overland flooding from stormwater racing down into the creeks, despite being above the flood level of the creek itself. But the council's future plans for the area would multiply the number of at-risk properties by a factor of 10 or 20.

Dozens of sites on floodprone land in southern Woolloongabba and Stones Corner are still zoned for highrise development. As long as developers build 50 centimetres above the (now out-dated) 1% AEP level defined by the 2013 Norman Creek Flood Study, the council will approve them to add thousands of additional residences to this volatile, vulnerable floodplain.

Screenshots of southern Woolloongabba from City Plan 2014, with the second image showing the Flood Overlay: all the warehouse/commercial properties shown in orange and dark red are currently zoned for high-density highrise - many of those sites are floodprone

But today's developers, city councillors, and urban planning public servants won't have to deal with the rising insurance fees and recurring annual disruption of low-level flooding – future residents and businesses will.

Each new development affects the way water flows through the catchment, particularly because many new highrises (including those further up the hills) are being approved with even smaller deep planting areas than the city plan's 'acceptable outcomes' technically require. The rules are already too lose, but the council isn't even enforcing them.

Personally I suspect one of the reasons the council hasn't yet commissioned a new flood study for the Norman Creek catchment is that updated modelling based on the 2024 AR&R guide (rather than 1987), would likely lead to more development sites being added to the Flood Overlay.

A Stones Corner development site on the edge of Hanlon Park was rapidly inundated by Norman Creek floodwaters on Sunday, 1 December 2024 after some parts of the catchment received 88mm of rain in two hours - image credits to Reddit users Juiced Pixels and BronsenAU

After the 2022 floods, then-Deputy Premier Steven Miles said Queensland must "ensure that going forward, we're not building new homes on locations that are prone to flooding or other natural disasters."

That hasn't happened. In fact, with new changes like the deceptively named 'Kurilpa Sustainable Growth Precinct' Temporary Local Planning Instrument (over in West End/South Brisbane), the council and the state government have both signed off on even more intensive development within the city's floodplain. But the particular problem with the Kulpurum/Norman Creek catchment is just how quickly flooding can occur, and how hard it is for the authorities to issue timely warnings.

Whereas river flooding of the West End peninsula can be predicted further in advance, as dams fill and the creeks far to the city's west start rising, a single so-called 'rain bomb' could dump enough rain in just two or three hours to cause major flooding throughout low-lying parts of Woolloongabba, East Brisbane, Norman Park, Stones Corner, Coorparoo and Greenslopes.

The takeaways

For anyone who is considering living within Norman Creek's floodplain long-term (or establishing businesses there), here are some insights to keep in mind:

- as of December 2024, the council's Flood Awareness Maps, which show which properties will flood and how deep the floodwaters could get, probably underestimate the likelihood and extent of potential creek flooding between Greenslopes and East Brisbane/Norman Park

- many of the newer developments which are advertised as being raised 'above the flood level' actually could still flood if the catchment gets heaps of heavy rain within a short space of time (your apartment might be higher, but your elevators, electricity and garbage collection could be affected)

- even where actual residential homes are raised high enough to avoid internal flooding, regular inundation of streets and key infrastructure is going to have long-term impacts on residents' quality of life and ongoing costs (for both the council and individual residents)

- if Australian companies continue digging up and exporting more coal and gas, the flood risk to your property will likely increase even faster

If you hear talk of possible floods, you can check the near-real-time creek levels yourself as measured at the Caswell Street, Ekibin Park South and Joachim Street flood gauges. The Caswell St gauge is best because it's downstream from the inflow of Coorparoo Creek, but it's still upstream from where Bridgewater Creek and Scott's Creek flow into Norman Creek, so it won't pick up the full impact of rain falling in the Coorparoo/Camp Hill/Norman Park end of the catchment. You can also check rainfall totals for different parts of the city via this map, which is updated hourly.

Right now, the Norman Creek catchment's significant flood risk isn't properly reflected in property prices. Real estate agents routinely downplay or lie about the flood vulnerability of the properties they're advertising. I've seen houses in my neighbourhood that were inundated in 2022 selling for $1 million+. Unfortunately, a lot of people who've been caught up in the property market frenzy will be dealing with unworkably high insurance costs in the coming decades.

The situation playing out on Kulpurum's floodplain is a microcosm of failures across the city and wider state. Both major parties are still in denial about the full reality of global warming. And both are still heavily influenced by the property industry, which not only objects strongly to any proposed changes that might restrict floodplain development, but successfully argues for further relaxations and increased density in these areas. The stench of corruption is even stronger than the smell of river mud.

Politicians, real estate agents and property developers prefer not to talk about it, but the creeks are still there, hidden away in stormwater drains just a couple metres below the surface, waiting to rise again.

Even if our leaders would rather forget, local residents will be wise to remember.

Thanks for reading! There's very little independent, locally-specific commentary and analysis of this kind in Brisbane (although you can find plenty of developer puff pieces that paint a very different picture). So if you value articles like this being available for free online to the wider public, please consider signing up for a $1/week subscription.

If you can't afford to subscribe, you can also support this work by copying the web link – www.jonathansri.com/normancreekfloods – and sharing this article on local social media groups.

Member discussion