Towards a new political orientation for the Greens (part 2)

If you haven't already read part 1 of this article, check it out first...

A mismatch?

There’s something profoundly incongruous about a political movement that says it’s concerned about urgent issues like climate apocalypse, genocide, mass homelessness etc. (and even supports protesting to draw attention to these issues), but whose elected representatives diligently follow parliamentary conventions, politely waiting their turn to speak dispassionately on bills about minor alterations to customs tariffs (or whatever).

If we know the political system has been hijacked by big business and that debates on the floor of parliament are mere charade, what effect does it have on our broader movement for social change when our elected representatives act as though the political system is still ethical and democratically responsive?

Why do Greens MPs cheer enthusiastically when workers in other professions risk their jobs to engage in disruptive civil disobedience, but rarely use their own far bigger platform of parliament to make similar gestures of defiance? Speaking as a former local politician myself, I feel there are a few inter-related explanations for this. The weight of social convention and institutional pressure, the sense of obligation to supporters who helped us get elected, and the dangled carrot of incremental reformist wins if we do conform, all discipline us into acting more-or-less like other politicians. It takes a lot of energy and self-belief to break those rituals and conventions.

But you can see why some voters might wonder: If an issue like global warming or mass homelessness is really as serious as the Greens say it is, why don’t Greens politicians reflect that urgency and seriousness through their behaviour in parliament?

When politicians do defy parliamentary norms in ways that reflect the gravity of their causes, they can have a far greater impact on public sentiment and wider discourse. Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke’s recent, defiant Haka in the New Zealand Parliament stands out as an object lesson in how to use the platform of parliament to engage the disengaged and spread important messages. By breaking parliamentary conventions, she signalled that she didn't have faith that playing by the system's rules would bring about positive change, thus galvanising thousands to join the wider social movement, which in turn reinforced her reach and political influence.

Meanwhile, the Australian Greens’ current approach seems to be running up against the same limits that Greens movements in many other countries have encountered (see the Irish Greens as one recent, particularly striking example of the risks of collaborating with centrist parties and contorting to fit the dominant paradigm).

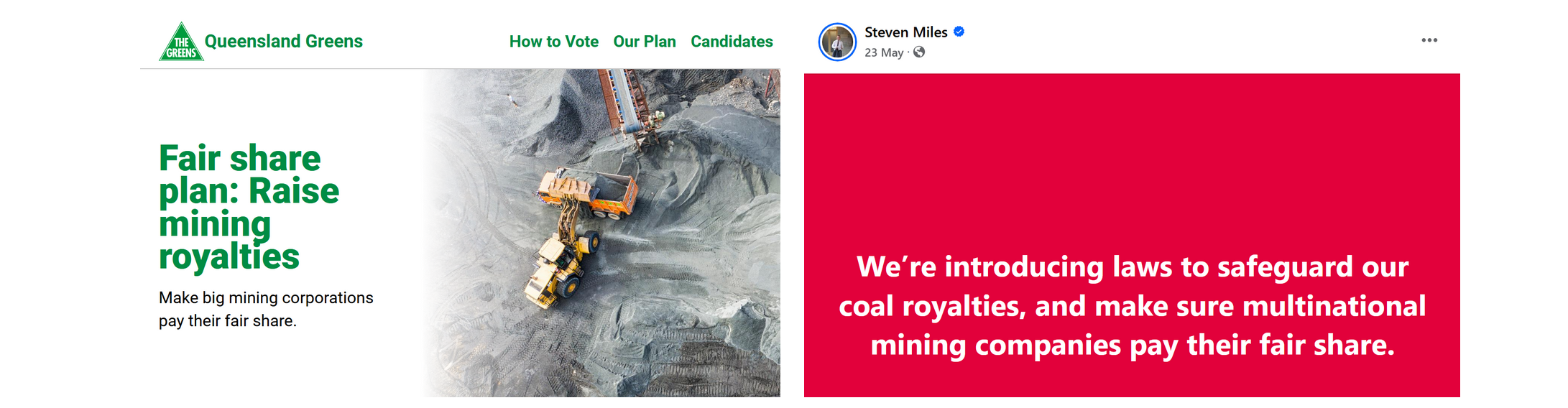

As we learned in the Queensland state election, when the Greens run on a reformist, statist social democratic platform, it’s easy for Labor to adopt some Greens messaging and rhetoric, and announce a few policies that seem similar to Greens demands (even if the details are very different). Less-engaged progressive voters won’t perceive the strong distinction between the two parties, and can easily swing back towards Labor, whose resources and media reach make it seem more politically potent. Meanwhile, any Liberal voters and anti-establishment voters we might've otherwise won over are turned off by our ‘pro-big government’ image, or will blame the Greens by association for stuff they're angry at Labor about.

If the Greens narrative was more explicitly and consistently “the whole system is broken so we’re not going to do this dance with the major parties” the decision to block crappy Labor bills and take stronger negotiating positions might make more sense to voters who are only superficially paying attention. But if the overall image you project is that you’re actually kinda similar to older political parties who you’re simply hoping to replace without transforming the whole system, being perceived (rightly or wrongly) as unwilling to compromise seems inconsistent with the role many voters expect you to play.

Does the parliamentary strategy adopted by Greens MPs align with our broader movement's demands for deeper change?

Are we sending mixed messages when we say certain issues are 'urgent' but our MPs don't seem to be acting with urgency?

Is the parliamentary wing of our party inadvertently signalling to supporters that other forms of activism are less of a priority?

Side-stepping anti-colonial resistance?

Recently, New Zealand's Green Party co-leader Chlöe Swarbrick delivered an inspiring speech against the conservative National Party's Treaty Principles Bill. It was a solid case study in how non-Indigenous politicians can articulate a nuanced critique of settler-colonialism and capitalism that doesn't simply reinforce 'us vs them' binaries between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

But I found myself struggling to imagine Australian Greens leader Adam Bandt or senate leader Larissa Waters delivering a similar speech. Deputy Leader Mehreen Faruqi probably would. But most Australian Greens MPs tend more towards social democracy than anti-colonial political philosophies.

Meanwhile Senator Lidia Thorpe has articulated a strong critique of western imperialism and settler-colonial nation-states. But she evidently found it difficult to reconcile her values and tactical approaches with the dominant tendency of statist reformism that the federal Greens party room had settled on.

Lidia's individual political brand and messaging hasn't been directly tested at an election (and may not be; she has suggested she won't recontest when her current senate term ends). But it's worth noting that after a relatively short time in federal parliament, she has amassed more social media followers than most Greens MPs. Social media numbers obviously aren't the be-all and end-all of politics, but they're not irrelevant either – they're a rough indicator of how many people care about what a politician has to say.

Based on the numbers in parliament, Lidia's views shouldn't matter very much. How she actually votes in the senate generally has no bearing on whether the government can pass legislation or not, and because she doesn't have a political party, no-one is really worried about losing votes to her in the way they worry about Hanson and One Nation. In parliamentary terms, Lidia is politically irrelevant. And yet she has still built up huge public influence by offering an uncompromising anti-establishment critique of racism, colonialism and border imperialism.

Looking around Australia and across the world, it seems that generally speaking, left-wing, statist social democracy political programs haven’t been able to build and sustain mass movements of support that can consistently win elections and transform society. Take, for example, the 2019 UK election result. Whatever particularities we might point to in terms of Brexit, voting systems etc., Jeremy Corbyn’s bold but reformist social democracy manifesto evidently wasn’t enough to counteract the right’s xenophobic nationalism, particularly among working class voters who it hoped to appeal to.

At the same time though, we seem to be living through a period of widespread, growing interest in anti-colonial/anti-imperial/anti-racist politics. Manifestations vary according to contexts. But there are common threads from Black Lives Matter, to Justice for Palestine, to protests against Prince Charles's recent global tour, to Indigenous land rights movements across South America, to Aoteoroa's huge campaign in defence of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi).

These political movements are generally much more critical of nation-states and centralised governance. Racial justice platforms argue for deeper, wider transformations, often articulating powerful solidarities between the interests of First Nations and other racialised peoples. They challenge the foundational myths of capitalist-colonialism more directly, including explicitly critiquing police, prisons and other mechanisms of top-down government control.

Some thought leaders in the Greens – particularly those who've advocated the social democracy left populist shift as the best way of connecting with non-Greens voters – avoid talking too much about colonialism because it’s seen as ‘divisive’ territory that undermines coalition-building potential. The above-mentioned strategic orientation – of uniting people around the common enemy of billionaires and mining corporations – leans away from talking about redressing the injustices of colonisation in the hopes of creating as big an 'us' as possible, arrayed against a small, privileged, elite 'them.'

But the tens of thousands of Kiwis who showed up for Aotearoa's November 2024 treaty protests certainly weren't all Maori. Plenty of non-Indigenous people were also drawn into the campaign and inspired to take part. While such topics are polarising, and no doubt turn off some people, the 'us' coalitions that can be built around anti-racist and anti-colonial struggles are still broad and powerful.

Meanwhile here in so-called Australia, tens of thousands are willing to give up their morning on Invasion Day to march through scorching streets and hear from Aboriginal activists, academics and elders. Brisbane's 2020 Black Lives Matter rally still holds the record for the single largest protest in the city since the anti-Iraq war rallies of 2003. And hundreds – sometimes thousands – of people regularly mobilise to march in solidarity with the people of Palestine, or Afghanistan, or Sudan, or Tibet.

But the average Greens MP would likely struggle to get more than a couple hundred people to show up to a public meeting, or to actively volunteer for them on their re-election campaigns. I wonder if this might be telling us something important about what political visions and approaches people feel are worth their time and energy.

What would it look like for the Greens to adopt a political posture that more closely aligns with First Nations demands for reparations, land back and anti-extractive ecological stewardship?

Could we build a broad coalition for social change that centres anti-racism?

Whose rules are we playing by?

Electoral politics disciplines those who engage with it in many different ways, particularly in terms of reducing broad movements for change into siloed lists of discrete demands. This 2015 Crimethinc article says it better than I can:

"The truth is that practically all movements are wracked by internal conflicts over how to structure themselves and how to prioritize their goals [...] Forcing a diverse movement to reduce its agenda to a few specific demands inevitably consolidates power in the hands of a minority. For who decides which demands to prioritize? Usually, it is the same sort of people who hold disproportionate power elsewhere in our society [...] The marginalized are marginalized again within their own movements, in the name of efficacy.

Yet this rarely serves to make a movement more effective. A movement with space for difference can grow; a movement premised on unanimity contracts. A movement that includes a variety of agendas is flexible, unpredictable; it is difficult to buy it off, difficult to trick the participants into relinquishing their autonomy in return for a few concessions. A movement that prizes reductive uniformity is bound to alienate one demographic after another as it subordinates their needs and concerns."

- 'Why we don't make demands'

Although not perfect, the original article is worth a read in its entirety, and is definitely applicable to movements like the Greens.

The political establishment likes compartmentalising people's frustrations into particularised demands about narrowly defined 'issues,' for which responsibility can be dispersed across various ministerial portfolios. A tunnel vision focus on specific issues that can be solved with particular 'policy solutions' obscures the connections between different experiences of injustice and marginalisation, and makes the need for deeper, wider transformation less obvious. It's reinforced by the media, PR advisers and polling companies – "what issues are voters most concerned about?" – but also by NGOs, unions and other issues-based advocacy groups who think they have a better chance securing wins if they don't dilute their message with broader systemic critiques.

The Greens are on weaker ground if we settle for contesting elections on such terms, training our own supporters to think more like bureaucrats than agents of deep change. In many Greens campaigns, doorknocking volunteers are instructed to ask voters (after some initial rapport-building) "what issues are you most concerned about?" and to then try to match those concerns to a list of initiatives that the party has announced. For some voters, this approach works. But not everyone thinks about the world in terms of government departments and discretely defined policies. And green politics doesn't really work like this either.

Green critiques of capitalism/colonialism/heteropatriarchy are holistic – we understand the inextricable connections between housing, health, education, sustainable environmental management etc. These are not siloed 'portfolios' that can be reformed in isolation from each other. Treating voters as though they're simply making a choice between competing parties' shopping lists of policy changes is stultifying for political discourse. For a minor party, it's a strategic dead-end.

This is because when the Greens articulate a reformist social democracy policy platform, the conservatives (both Labor and the Liberals are now conservative parties) are still going to attack us for being radical extremists, while dragging us into technocratic debates about policy detail that muddy the waters and bore most voters. Simultaneously, to avoid losing too many of its more progressive supporters to us, Labor can adopt watered-down versions of a few specific Greens policies (key differences won't be obvious to disengaged voters), insulating against us without having to contemplate bigger systemic changes. The LNP hold off One Nation in a similar way.

If your pitch to the electorate is essentially "Here are five to eight proposed policy changes to address five to eight discrete issues," but a lot of middleclasss voters only feel like two or three of those issues are actually pressing concerns, you're not necessarily making a compelling case for switching to a new political party, let alone for system change. And if you haven't made a clear case for system change, your own supporters mightn't be prepared for the very strong negotiating approach – including being willing to block multiple government bills – that's required to actually secure wins even on those reformist policy goals.

Rather than campaigning on specific policies, the details of which can be endlessly debated, and which we're unlikely to be able to implement in full anyway, are we better off focusing on core values and broader objectives?

Three areas for change – the message, the mechanisms and the mission

This is not an over-simplistic discussion about ‘how radical’ Greens policies should be. I’m not placing myself on one side of a ‘sacrifice power to remain ideologically pure’ vs ‘compromise pragmatically for tangible results’ false dichotomy – I’m rejecting that frame of analysis altogether. The Greens need to consider a fundamental transformation of the messages we take to elections, the way our party works internally, and how elected Greens members use their power and platform.

This isn’t just a question of picking slightly different policies or slogans. To succeed in a hostile electoral environment – both winning votes and securing material changes – the Greens need to adapt to today's political context. The party's aesthetics and methods must align with our messages and broader political vision.

What that looks like is beyond the scope of a single article, and shouldn't be defined by any one individual or vanguardist manifesto. But here are some ideas that Greens supporters should be grappling with...

A vision beyond big government?

As I've written about previously, a social democracy platform that imagines a bigger role for top-down centralised governance and service provision might not be good policy. But right now in Australia, it's also not necessarily good politics – it's not as popular with voters as the Greens might wish.

In certain electorates, the Greens have found just enough people who are frustrated enough with current government administrations that they are willing to change who they vote for, but who still have faith that the Australian nation-state could be reformed. Many of these voters really like the party's social democracy platform, but their underlying resistance to deep change means they can easily be turned against the Greens by propaganda that the party is 'too radical' or 'uncompromising.'

In most electorates though – especially outside the capital cities – the majority of voters have so little faith in the capacity of government that talk of centrally-controlled renewable energy mega-projects, or public developers building hundreds of thousands of dwellings, doesn't cut through, and even turns people off.

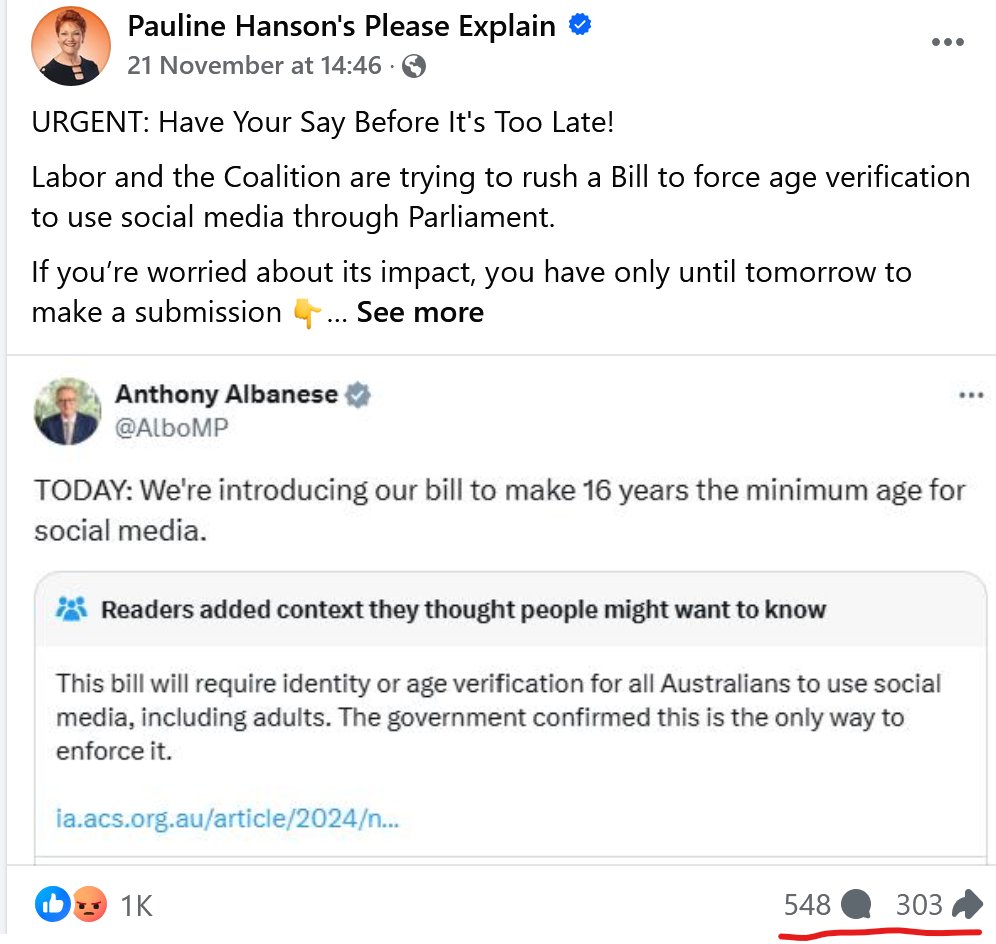

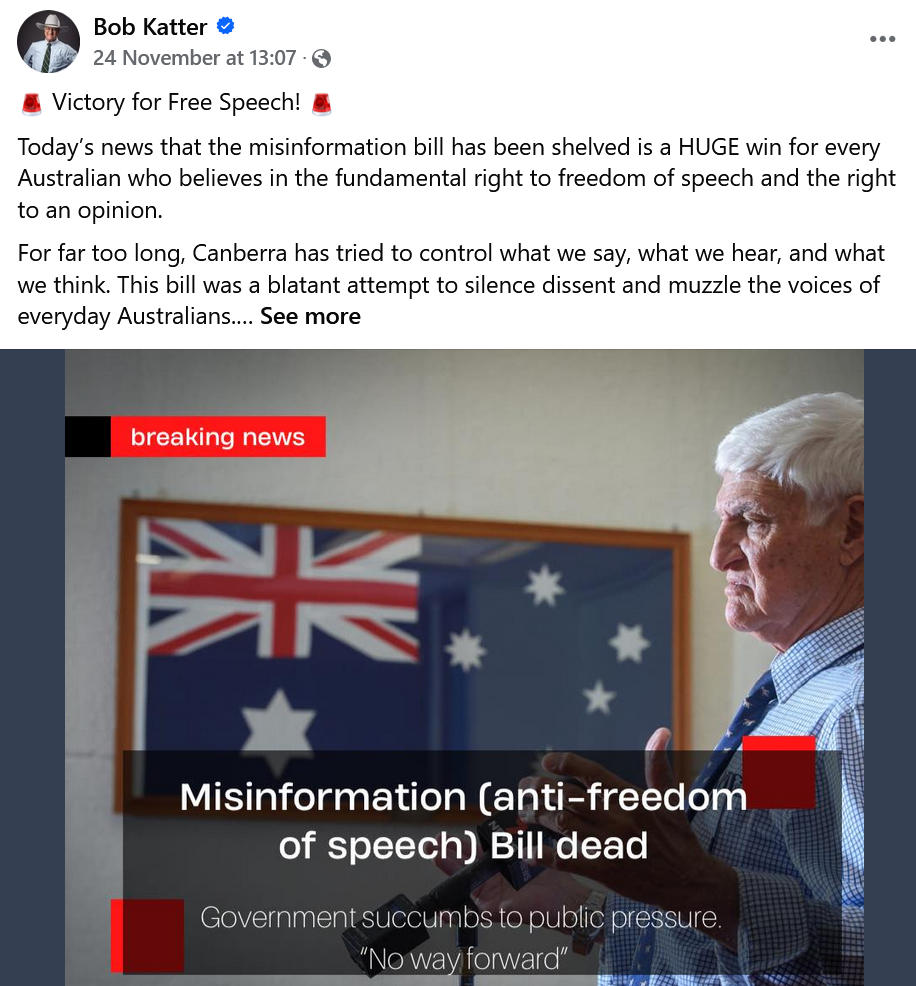

Meanwhile, there's a substantial groundswell of support for a politics that challenges government surveillance and the erosion of civil liberties. A Greens platform could easily connect such concerns to critiques of militarism and the US alliance, defending our human rights to protest and organise collectively, and resisting special treatment for big corporations. But at the moment, this political energy is largely being captured by the right (despite actual parliamentary voting records).

Right-wing demagogues are claiming political territory opposing government surveillance and control (while positioning the Greens as part of a 'pro-big government' 'elite')

If I was rewriting the Greens messaging guide for future elections, I'd be asking myself if the party should focus less on specific policies, and more on core values and political principles. Importantly, we should consider whether focusing on statist policy solutions at a time when scepticism of government is so high risks alienating voters who we might otherwise win over if we offered a sharper critique of how big corporations and governments are invading our private lives.

Maybe this would also open up more space for deeper Greens conversations about decentralisation and decolonisation. Critiquing settler-colonialism is more straightforward when you're not simultaneously arguing for government-run mining enterprises on Aboriginal land.

Embracing pluralism and flexibility

As the Greens have grown, party control over aesthetics, messaging and policy positions is feeling more centralised and top-down. In theory, this supposedly ensures individual spokesepople aren't committing the entire party to fixed positions without collective consensus. But in practice, it means messages and narratives are tightly controlled by small groups of people – mostly paid staffers – who occupy powerful positions within the party hierarchy, and try to dictate to candidates and volunteers what they should and shouldn't say.

Consequently, the party sometimes makes the wrong call, completely missing issues and angles that voters really want us to talk about. Volunteers and spokespeople are discouraged from trialling different messages and adapting organically as they learn from each other. Instead, the party leadership picks a narrower, more uniform narrative for each election, upon which the whole movement rises and falls. Open debate about party strategy is discouraged for fear of undermining the 'unified front.'

While there are good reasons for encouraging message discipline and recognisable branding, 'consistency' can too easily tip over into rigid, soulless orthodoxy, preventing the party from responding nimbly as the political landscape shifts. Increasing insistence on 'toeing the party line' also makes the Greens seem more like the major parties, and undermines claims that we're doing politics differently.

Instead, the Greens could adopt a more pluralistic and decentralised approach: Encourage supporters to talk about whatever they feel is important to voters in their networks, and if they're ever sharing views that contradict party policy, make clear they're only expressing a personal opinion. This would foster a more intellectually engaged movement, rather than reducing the majority of candidates and volunteers into talking billboards who are trained to only repeat the party line. Members would have more flexibility to adapt their messages to local contexts and audience niches, as long as they stayed within broad parameters of party values. Crucially, this would allow the party to make better use of the talents of its large and diverse supporter base.

Are rigid hierarchies and reductive uniformities creating too many bottlenecks and barriers that restrict the blossoming of a diverse, multi-faceted movement?

Democracy where it matters – a parliamentary strategy that centres the people

As mentioned in part 1, over the current term of federal parliament the Greens have mostly voted in favour of Labor bills whenever our support was needed in the senate. But we have still been heavily criticised for obstructing government reforms, while also being tarnished in some voters' eyes for our perceived support of Labor's overall agenda. This strategy has hurt our electoral fortunes, but hasn't yielded many tangible policy wins.

We end up with only minimal power to drive and implement our own agenda, and we're also blamed for whatever people are angry at the government about. Meanwhile our politicians are endlessly second-guessing themselves, obsessing over polls, survey responses and election results like tea leaves, trying to discern how the majority of voters actually want them to vote on a given bill.

The toughest decisions – the ones that tend to cause electoral damage among swing voters and demoralise our most loyal supporters – are when Greens reps have a deciding vote on a bill that offers some minor positive improvements, but which overall doesn't quite line up with party policy. If passed, such bills will often create a political climate where further reforms in that field of government responsibility are delayed for years. So in practice, saying 'yes' to the immediate minor reform usually also equates to saying 'no' to bigger changes.

A better approach would be to democratise such decisions: Rather than a handful of Greens politicians making this crucial choice behind closed doors, put the question to a public plebiscite. Senators could give every resident in their state an opportunity to vote on whether their Greens reps should support or block the controversial government bill.

At first, only a few thousand people might be expected to participate in plebiscites like this. But as voters see Greens reps aligning with the results, participation rates will rise (this isn't an untested theoretical hypothesis – as a city councillor I trialled various forms of community voting for several years).

The people who participate won't be 100% demographically representative of the entire electorate, but they will represent a much more diverse range of perspectives and life experiences than the Greens politicians and staffers who would otherwise be making such decisions. For each bill on which the Greens conduct a public plebiscite, the participating cohort is likely to include a significant proportion of actively engaged Greens supporters, as well as other non-aligned people who are particularly passionate about the subject matter of the bill in question. Less engaged people who aren't across the details and don't have an informed opinion will tend to opt out.

In the lead-up to a public vote, Greens reps would be free to express their own personal opinions about whether the bill should be supported, and could coordinate their own forums and information sessions to ensure participants will be as informed as possible.

Advocacy groups and unions could also be expected to make recommendations to their supporters, creating a richer and more robust democratic debate. While for some bills, profit-driven corporate interests may try to manipulate voters with their own propaganda campaigns, it's generally harder and more expensive to manipulate hundreds of thousands of the most politically engaged citizens than it is to manipulate a few dozen politicians.

Remember: such votes would only be held in situations where the existing Greens policy platform doesn't provide clear guidance – there's little chance this approach would lead to Greens parliamentarians voting to lock up refugees or bulldoze native forests; the party's policies already tell them how to vote on those kinds of proposals.

Widespread internet access means facilitating such votes is much cheaper and easier than it was back when the Australian Democrats ran similar postal votes among their own members. Greens senators get ample advance notice when the government needs their support to pass a bill, and if Labor tries to spring controversial decisions on the party without warning, it would be easy (and politically defensible) for our MPs to abstain from that parliamentary vote and insist they need more time to consult constituents.

Distributing power over these key parliamentary decisions would empower Greens members and the wider public, insulate MPs against co-option by the system, provide them with a more solid basis to justify and defend their voting choices, and demonstrate a genuinely transformational approach to electoral politics.

In Australia, the only recent example resembling this approach is Senator Jacquie Lambie's decision in 2020 to conduct a public poll on whether she should support Scott Morrison's bill to deny imprisoned asylum seekers access to mobile phones (and expand other Border Force powers). Lambie's poll was open nationwide (not just to constituents of her own state), and unlike my local council community voting trials, the results weren't published in real-time. In the end, over 100 000 people responded, with 96% of respondents opposing the mobile phone ban, and Lambie blocked the bill.

While such mass democracy approaches aren't perfect, and online voting systems must be designed carefully to resist fraud, they're definitely worth consideration. Their use would more clearly distinguish Greens politicians from system insiders, while insulating the party from criticisms that it's disconnected from popular sentiment or 'too radical.'

Beyond a more democratic approach to wielding power within parliament, Greens politicians should also continue exploring more creative and subversive uses of their platform. Symbolic stunts, disruptive protests, smuggling in bluetooth speakers to play the testimonies of oppressed people – everything should be on the table.

When this Taiwanese politician physically snatched a bill on the floor of parliament to delay its passing, his actions aligned with the strength of his convictions, and he successfully drew wider public attention to the subject matter... every tactic needs to be judged (within its specific context) for its effectiveness at influencing debate and building movements

Parliament is a theatre stage where the most astute political actors use their platform to shape public discourse, and in turn voting patterns. The real decisions are made elsewhere, behind closed doors. Greens MPs should remember that their primary audience is not the other politicians in the building, but the wider public, and that most people won't pay much attention unless you give them a good reason to. We make ourselves relevant through the actions we take.

Scott Morrison's 2017 stunt of bringing a lump of coal into parliament was an effective intervention in public debate - Bandt was right to respond at the time by bringing in a solar panel, though Morrison had the advantage of novelty/originality

So could it happen?

The new orientation I've sketched out here would represent a far deeper transformation than the party's anti-austerity, social democracy policy shift over the past 8 years. Unlike a simple change in messaging emphasis, it's not something that can be trialled meaningfully at the scale of a single seat or local campaign. Such a dramatic change in political orientation has to be reflected by the approach of incumbent Greens MPs and the party hierarchy as well.

The LNP's current majority in Queensland leaves more latitude for the Greens to experiment with such a strategy at the state level if the party's two senators and three federal lower house MPs are on board. But even a reorientation within one state would be difficult if Adam Bandt and the rest of the federal party room are still portraying a more centrist, system insider image.

Obviously we don't know how well this reorientation would work until we try it. Some people reading this article will no doubt dismiss my proposal as naive and idealistic, but I suggest it's actually more pragmatic approach than the party's current have-it-both-ways posture, which has demonstrably failed to yield results.

Adam Bandt has recently made comments which could be interpreted as signalling an even more conciliatory strategy of centrist compromise (I hope that's not his intention), agreeing to support centre-right policies for fear of 'letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.'

We can already see exactly where such paths lead by looking at the modern Australian Labor Party. That's not a road we should follow any further. But are we brave enough to fight for real change?

I'm very interested in hearing others' opinions on these ideas (you can leave a comment below).

Writing articles like this takes a lot of work. I'd love to be able to put more time towards political commentary and analysis, including interviewing other political thinkers to broaden the conversation. If you want to see more of this kind of writing, and perhaps even a few more videos that make these ideas accessible to a broader audience, please consider signing up for a $1/week paid subscription.

Please also take a moment to share this piece on social media or forward it to friends who might be interested.

Member discussion