Towards a new political orientation for the Greens (part 1)

This 2-part article was written on Yuwi country, while I was staying at a beautiful reforested acerage about 30km southwest of Mackay, along the Peak Downs Highway (which leads out to some of the largest coal mines in the world). I offer my deep respect and uncompromising solidarity to the rightful Aboriginal owners of this land, and my thanks to my generous hosts.

I'm sharing this in the hopes of prompting further conversations, and to unpack some of the questions I've been mulling lately. I don't intend for it to be treated as a prescriptive manifesto or clarion call. To the extent which I draw definitive conclusions and advocate specific strategies, I hope they're received with an open mind... (Part 2 is available at this link)

One of the hidden risks of engaging in electoral politics is that it can narrow our political horizons even when we think we’re actively pushing against co-option.

On one front, we might be shifting the Overton Window, drawing back curtains and even tearing out entire window frames as we broaden the parameters of debate. But simultaneously, on the other side of the house, we’re reinforcing walls that exclude a much wider range of political possibilities.

Meanwhile, catastrophic global warming is accelerating– our governments are still approving new fossil fuel projects – and younger generations are (on average) facing harder, more precarious lives than their parents and grandparents. Unfortunately, the party that's advocating most strongly for climate action and economic justice seems to be in denial about the changing political climate.

Over the past 8 years or so, the Australian Greens have gradually shifted towards what some describe as a ‘universalist’ or ‘left populist’ political orientation. This is essentially an anti-austerity social democratic vision which is more ideologically consistent and well-rounded than Greens positioning in the early 2010s, but which de-emphasises grassroots participatory democracy, and is not overtly critical of nation-states and centralised, top-down governance.

Arguably more influenced by left-wing electoral movements from western Europe than by revolutionary political programs in other settler-colonial or 'post'-colonial countries, this left populist, social democratic platform is characterised by a preference for policies and election campaign announcements that:

- advocate public ownership and control by nationalising key services and industries (e.g. nationalising electricity retail) or setting up government-run alternatives to private corporations (e.g. a public mining company, a public property developer etc.)

- make big corporations and mega-wealthy individuals ‘pay their fair share’ to fund better public services and facilities (this has focussed on taxing corporate profits and raising mining royalties, rather than redistributing existing private wealth such as via inheritance taxes or directly seizing billionaires’ ill-gotten assets)

- prefer universal access over means-testing (e.g. rather than calling for free public transport or free childcare only for people on low incomes, and inviting endless divisive debates about who shouldn’t and shouldn’t be eligible, we advocate for free public transport and childcare for everybody in society)

- focus on meeting immediate material needs that are common to very large constituencies of voters

This last one is important. The party – especially in Queensland – has shied away from election initiatives where the benefits to individuals are less direct and obvious. Our Greens MPs all care deeply about preventing tree-clearing, but during election campaigns, you probably won’t see the party announcing proposals to create more national parks or reforest degraded grazing land. Key strategists assume that most genuine environmentalists already vote for us, and talking about planting trees doesn’t win us as many new voters as free school lunches. These days even our commentary about climate change is focussed less on ‘saving the reef’ and more on creating new jobs in renewable energy industries.

The left populist shift centred on a stronger rejection of neoliberal austerity narratives; we didn’t have to cut funding in one area to increase funding for other stuff – we just had to tax big corporations more. But the 'universalist' element ends at the nation's borders. Even though a significant component of Australian corporations' profits come from exploiting the human workforces and natural resources of other countries, we're not proposing to use that extra tax revenue to provide free dental care to every West Papuan, or to build public housing in the Congo.

Still, it’s a reasonably big change compared to Greens policies of the early 2010s. Today, the party is calling for free tertiary education and abolishing student debt – a far bolder demand than the Greens' 2016 push to merely discount uni fees by 20% (and not touch existing student debt at all). Similarly, the party's 2016 position of means-tested access to partially-subsidised childcare looks pretty unambitious compared to its 2022 'universalist' policy of free childcare for every child (regardless of household income).

Broadening the message to broaden the base

The left populist shift has also lead to talking less about issues that might be more polarising. It's largely a change in emphasis and messaging rather than a more substantial change in policy goals or fundamental values. We might not talk much during election campaigns about refugee rights or protecting koala habitat, but those issues are still part of our policy platform.

If we aren’t winning over more voters, we presumably won’t have enough leverage, public credibility or institutional power to drive change on big issues like climate action, homelessness, weapons manufacturing or global food security. But party opinion-leaders have happily concluded that we’re in a fortunate position where many of the changes the Greens would like to make will also be broadly popular if we present them in the right way.

We don’t have to choose between a) advocating changes that win us more votes, or b) advocating changes that align with core Greens values and best support the long-term collective interest – winning more power and sticking to our principles need not be seen as mutually exclusive.

A possible summary of the underlying strategy is as follows...

If we are to fight back against corporate sector manipulation of the political system, and address major urgent crises like global warming, we need to build a broad coalition in support of major change.

With the exception of a small minority of powerful elites, there’s a lot more that unites us all than divides us. So we should avoid getting side-tracked by culture wars and potentially-divisive, less-urgent issues, and strive to find common ground wherever possible, forging allegiances across class, race and geographic boundaries. By making the big end of town pay more tax, and nationalising certain, profitable industries, we can offer everyone better public services and a higher quality of life – this is the fastest route to winning power and being able to implement a Greens agenda.

As one Greens campaign manager once put it, “unfortunately we’re going to have a hard time getting enough voters to support refugee rights or climate action when so many Australians are worried about paying their power bills and keeping a roof over their heads – we have to meet them we’re they’re at.”

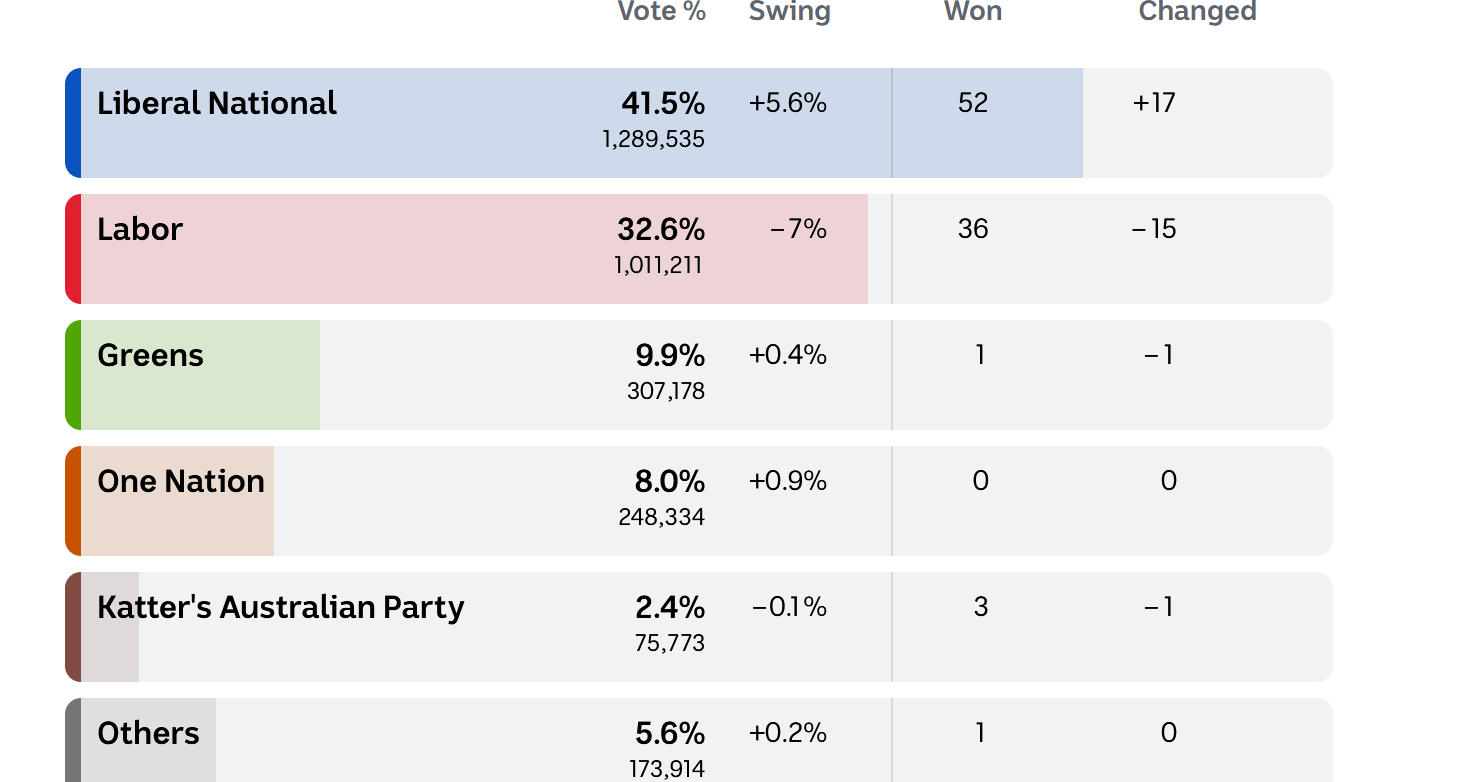

It may have worked for a few elections, in some regions

This shift has yielded some dividends for the Greens, particularly in Queensland. Meanwhile, in jurisdictions that didn't embrace it as quickly, the Greens vote stagnated over the same period (noting that the QLD Greens were partially insulated from other challenging factors at play down south).

However it’s possible that the recent Greens 'surge' in Queensland wasn’t necessarily because the shift in messaging emphasis won over more voters directly, but because it helped build buzz and attract volunteers. In turn, volunteer-intensive ground campaigning in key seats shifted just enough votes, even though overall statewide support didn't grow dramatically.

Looking at successive election results, there’s no strong evidence that the change in messaging and policy led to a big boost for the Queensland Greens outside of Brisbane. Some have suggested that’s simply because we didn’t have enough people on the ground to share our message with regional voters. But my impression is that the platform was never as compelling beyond South-East Queensland as some of the Greens leadership wanted it to be.

We did, however, do very well in the 2022 federal election. Looking back now, I think my explanation of the result at the time was largely on the mark.

Insofar as the ‘populist turn’ amounted to a more well-rounded leftist approach – a rejection of centrism and neoliberal austerity, and a broadening of the topics we talked about during election campaigns – it has worked to a point.

But once the Greens gain enough support to start winning seats, and the major parties see us coming, they develop strategies and allocate resources to keep us at bay.

The Queensland Greens' under-whelming 2020 and 2024 state election results suggest to me that the ‘bolder’ social democracy orientation has not been able to steadily and consistently win votes off the major parties once they put resources towards attacking us. Or at least, the party’s overall approach – including the policy platform – hasn't been satisfactorily resistant to the strategies that the majors and other political forces are using against the Greens.

In light of recent elections in Queensland, Victoria, and the ACT, where the Greens didn’t do as well as hoped, it’s important to unpack the limitations of the party’s current positioning (noting that we've also had better results in Northern Territory and NSW council elections). This isn’t just a question of winning votes, but of how we wield power.

A parliamentary strategy that hasn’t yielded results

Since May 2022, the Greens have held the balance of power in the federal senate on any proposed bill where Labor didn’t have support from the Liberal-National coalition. For the time being, balance of power – where Labor needs Greens support to pass bills – is seemingly the strongest position the party will hold within the framework of parliament.

It's important to underscore that while federal Labor has relentlessly attacked the Greens for 'blocking' and 'delaying' government bills, the Greens have in fact voted in favour of most pieces of legislation that Labor needed support for in the senate. This includes supporting pretty much every reform that federal Labor proposed regarding housing and climate action (one notable exception was the refusal to support Labor's Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation bill).

The party has done some great work at shifting the parameters of debate and building public support for Greens policies, as well as successfully moving minor amendments that improved various government bills. However, looking at the big issues and policy goals the Greens focused on during the last federal election campaign – free dental care, free tertiary education, scrapping property investment tax incentives, raising welfare payments, banning new fossil fuel projects etc. – there are no major tangible policy outcomes that the federal party room can point to as vindications of their current strategic approach.

They've also been unable to stop Labor making actively harmful changes, such as gutting the NDIS, further persecuting refugees, and increasing subsidies and funding for weapons manufacturing. There’s no indication that continuing with a similar parliamentary strategy if the Greens still hold the balance of power after the next federal election will yield bigger policy wins.

That’s not to say the Greens haven’t achieved some positive reforms – including $3 billion of additional funding for housing construction and $500 million of funding to upgrade existing public housing. And Labor is also making a few new election promises in direct response to Greens demands (e.g. wiping 20% off HECS debts).

But when I compare what I’d hoped the Greens might be able to achieve while holding balance of power for three years, to what we’ve actually gotten, the results are overall disappointing. They also don’t appear to be translating into huge numbers of voters switching to the Greens.

Similarly, within jurisdictions like Victoria, Tasmania and the ACT, where Labor has often needed Greens support to pass laws, closer Greens collaboration with Labor governments over the years has not delivered significant positive change of the scale our society needs, nor has it generated consistent growth in the Greens vote.

Undeniably, lots of voters feel that the Greens have been unreasonably obstructive, but you'd be hard-pressed to identify many Labor bills which the Greens actually blocked. Sustained propaganda (repeated by outlets like the ABC) has frayed the connection between public perception and reality. How we respond to this pressure is crucial. Will the Greens follow the path of so many other parties and movements throughout history that start out seeking change but become more conservative over time? Or can we be brave enough to nurture a genuinely transformational approach to politics?

Anti-establishment sentiment is rising, but not to the Greens' benefit

Everywhere that the unjust impacts of neoliberal capitalism are felt, frustration with governments (and any politician perceived to be part of the establishment) is rising. Swings to right-wing demagogues like Donald Trump evince this, but perhaps so too do the swings to ‘system outsider’ left-wing politicians like Brazil’s Lula da Silva.

The positive swings I received in all the elections I ran in (even in the same years that many other Greens candidates and incumbents weren’t seeing significant positive swings) might be explained in part by my more anti-establishment image and approach compared to most other Australian Greens reps.

In Australia, support for the two major parties is trending downwards, with more people swinging towards minor parties and independent candidates. But generally speaking, the Greens haven’t been able to attract as many of these disillusioned voters as one might hope.

This helps explain why in 2022, south-eastern states – where the Greens were already seen as more ‘establishment’ – saw a surge of support for ‘teal’ independents, in part from people who wanted reps that they perceived weren’t co-opted by the system. Whereas in Queensland – where the Greens had more buzz but weren’t yet seen as political insiders – there didn’t seem to be as much enthusiasm for Climate 200 independents (that 'outsider' perception of the Greens is changing in Brisbane too after our impressive 2022 federal result).

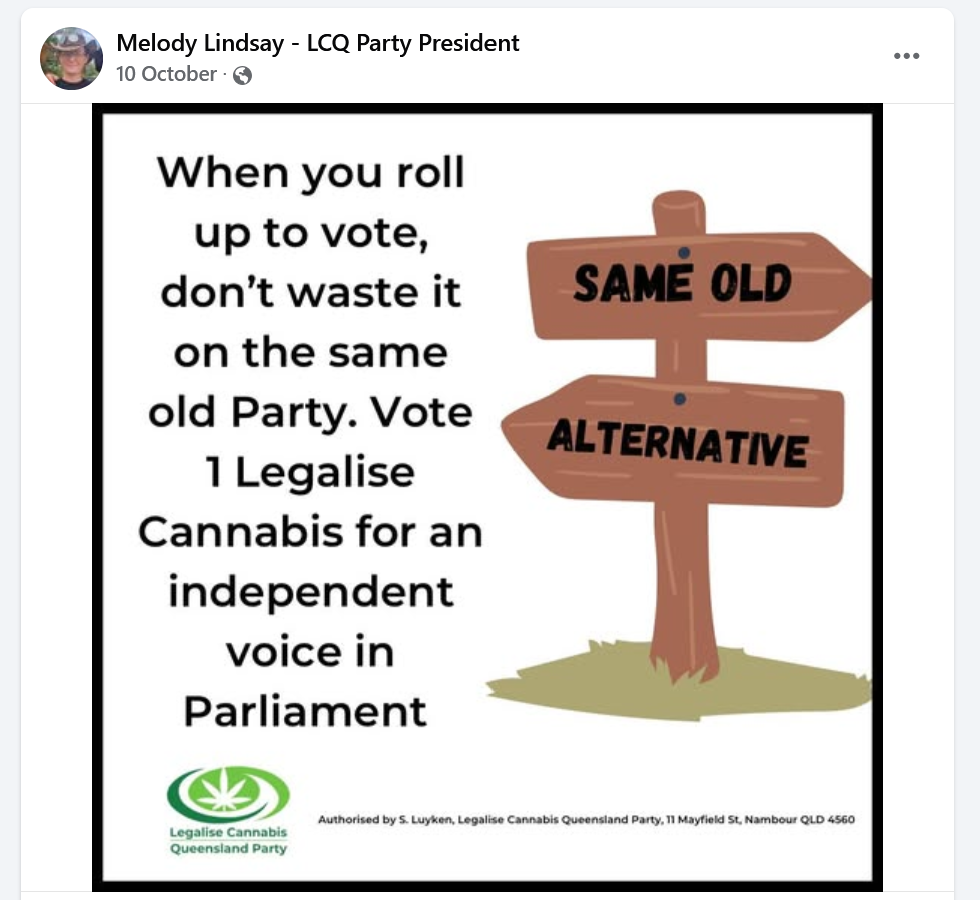

In the recent 2024 Queensland state election, in seats like Buderim, Caloundra, Gaven, Glasshouse and Logan, the Legalise Cannabis party – who had no significant ground campaign or much mainstream media coverage – picked up thousands of voters from the major parties, while the Greens primary vote barely changed. The party clocked a 7.7% primary vote in the Sunshine Coast hinterland seat of Nicklin against the Greens' 10.7%. In Bundaberg, LCQ hit a primary vote of 5.8%, outdoing the Greens on 3.4%, and in Hervey Bay, LCQ polled 7% vs the Greens’ 4%.

The Greens need to think more deeply about what this indicates, rather than simply concluding “well I guess legalising cannabis is the number one issue for a lot of people!”

Legalise Cannabis Queensland's social medial posts show how their positioning is just broad enough to appeal to anti-big government voters looking for a protest vote, even if legalising cannabis isn't their top issue

There’s more going on here. Despite minimal resources and no serious chance of winning seats, LCQ successfully drew in enthusiastic candidates and volunteers (and thus voters) who are frustrated with the major parties, on a platform that signals a strong cynicism of government. Outside of metropolitan Brisbane, Legalise Cannabis is evidently a more natural fit than the Greens for many voters who’ve turned against the major parties. Part of LCQ's support base are anti-vaxxers, but even the consolidation of anti-establishment anti-vaxxers as a political bloc partly reflects the Greens' failure to articulate a strong enough left-wing critique of government surveillance and bureaucracy.

Problematically for the Greens, while we’re still seen as a minor party without much structural power, many voters no longer see us as an outsider or anti-establishment party. This is the worst of both worlds: We’re not attractive enough to voters who've been seduced by centrism and want a powerful mainstream party that can credibly promise to ‘get things done;’ but nor are we necessarily winning over those who want to send mainstream power-holders a ‘stuff you!’ message.

I’ve had enough one-on-one conversations and read enough chat threads to see that some of the people swinging to the likes of One Nation aren’t doing so because they’re deeply xenophobic, but because they’re (legitimately) concerned about increasing government surveillance and interference in our lives. Parties like One Nation are speaking their language more than the Greens are, and their fear of the surveillance state is so strong that Hanson’s racism isn’t a deal-breaker for them.

While many Greens loyalists might feel resistant to acknowledging it, the blunt reality is that our elected representatives mostly present as system insiders who aren’t shaking things up. They see our MPs wearing suits, making dry speeches in parliament, spending money on flyers and billboard ads, and doing most of the other things that establishment politicians do.

For disengaged voters, the nuances of parliamentary voting records or the details of party policies don’t necessarily matter as much. If other political actors are reinforcing the message that the Greens are ‘just as bad as the major parties’ and our MPs seem (at a glance) to be similar to other politicians, disillusioned voters who are distrustful of government aren’t necessarily going to perceive the Greens as champions of system change. This is especially the case when the party contests elections via unapologetically statist policy platforms (by ‘statist’ I mean policies that place too much faith in the power of centralised top-down government).

Are we missing an opportunity to win over larger numbers of disillusioned voters because our aesthetics, style and core platform look too pro-establishment and 'pro-big government'?

Keep reading: Part 2 of this article continues at this link...

If you haven't already done so, you can support more of this writing by signing up for a $1/week subscription.

Member discussion