The future of Barrambin/Victoria Park: Stadiums or koalas?

In April 2021, Premier Annastasia Palaszczuk held a press conference at the Gabba Stadium, formerly the site of an Aboriginal pullen-pullen ground and a series of abundant waterholes, whose filling in has made low-lying parts of the suburb of Woolloongabba especially prone to flash flooding during heavy storms.

Many residents probably think of the Gabba as a colourful, busy place populated by raucous fans and professional athletes, but for the hundreds of days per year when it’s not used for major sporting fixtures, the pavilions stand empty and ominously silent.

On the morning of her press conference, Premier Palaszczuk’s carefully-scripted statement was repeatedly punctuated by a resident flock of crows, their caws echoing throughout the empty amphitheater. It was almost as though they were mocking her proposal, or at least asking why – if the current stadium was mostly empty for around 300 days of the year – we needed an even bigger one?

The Premier’s surprise announcement (even the Lord Mayor claimed he’d only been told about it the night before) was that the 42 000-seat Gabba Stadium – much of which was rebuilt relatively recently in 2005 at a cost of $128 million – was to be ‘renovated’ yet again in order to serve as the main 50 000-seat athletics venue for the 2032 Olympic Games.

Anyone paying attention to the required specs of an Olympics athletics venue could see immediately that this so-called ‘renovation’ actually meant a complete rebuild right down to the foundations. The Premier eventually confirmed this was indeed the case; the stadium was to be demolished, with a new one built on the same site at a staggering cost of $1 billion.

Later, this back-of-the-napkin cost estimate was revised up to an even more ridiculous $2.7 billion, but the revised cost didn’t include a further $300 million needed to relocate East Brisbane State School and secure suitable alternative venues for cricket and AFL matches. As post-pandemic construction costs continued rising, some commentators predicted the final project bill would likely exceed $4 or $5 billion in today’s dollars.

Thankfully, a persistent campaign led by Greens elected representatives and local residents forced the State Government to change its mind

In early 2024, new Premier Steven Miles announced that the Gabba demolition and reconstruction was cancelled, and that the existing athletics stadium at Nathan would be repurposed instead (at a projected cost of more than half a billion dollars – still a heck of a lot of money, particularly when the government is also claiming Queensland doesn’t have the money or construction labour force capacity to build more public housing).

But while the public backlash to this particular destruction/construction proposal had massive statewide political ramifications, it didn’t prompt a broader reconsideration of how much we’re losing with every new project, or deeper questions about whether Brisbane is destined to be a city permanently under construction.

Yet another stupid stadium proposal

This brings us to the zombie proposal (it just won’t stay dead!) to build new Olympic venues over a massive chunk of Barrambin/Victoria Park. The main proponent of this idea is the well-connected private architecture firm Archipelago, which among other things, makes a lot of money designing athlete villages for major sporting events.

At the state level, both major parties have claimed they don’t support the scheme, but the idea still won’t die because it has the support of Liberal National Party mayor Adrian Schrinner, and several of Brisbane’s major property developers. I worry that if the LNP were to regain power after the October state election, they would consider reanimating the concept. Hopefully it doesn't come to that.

It’s telling that the property industry and the LNP consider supposedly ‘vacant’ public parkland as fair game for stadium constructions, but would dismiss the idea of shutting down one of the massive horse racing tracks at Ascot to build public housing and sports facilities as fanciful.

Barrambin is not only the largest remaining green space in inner-city Brisbane, but also a significant site for local Aboriginal people. In the early decades of the colony, it was preserved from private development primarily because of its ongoing use by hundreds of northside Murris (and their visitors from further afield) as a major settlement, hunting area and gathering place. Aboriginal people – particularly the clan of Daki-Yakka (a local elder also known as the Duke of York) – held on stoically despite persistent attacks from white settlers, continually occupying the land in large numbers until at least the late 1870s.

The remnant waterholes beside the inner-city bypass are arguably among the most ecologically valuable parts of the park, as well as a legacy of the larger watercourses and pools that Aboriginal people used to rely on as a source of food and drinking water.

Archipelago wants Brisbane to construct a stadium directly on top of these waterholes, clearing hundreds of native trees in the process.

To most of us – whose vision isn’t cluttered by dollar signs – it’s obvious why inner-city green space needs to be preserved.

Larger parks are particularly important because the habitat value these contiguous spaces offer for wildlife is significantly greater than an equivalent area of several smaller parks separated by major roads and buildings. But they also offer a specific kind of amenity for urban residents who are craving immersion in nature and respite from the concrete jungle – something you simply can’t get in smaller parks that are completely surrounded by tall buildings.

Within 5km of Brisbane’s CBD, there are no other parks that come close to the size of Barrambin/Victoria Park. Once we build over it, Brisbane won’t have any other green spaces like it for decades – perhaps centuries – to come.

Paving paradise

Victoria Park has shrunk repeatedly over the years as a result of various projects, from new roads and on-ramps to incursions from neighbouring school and university facilities. Each of these construction projects has created something new, but also destroyed parts of this publicly owned green space and the latent potential it holds.

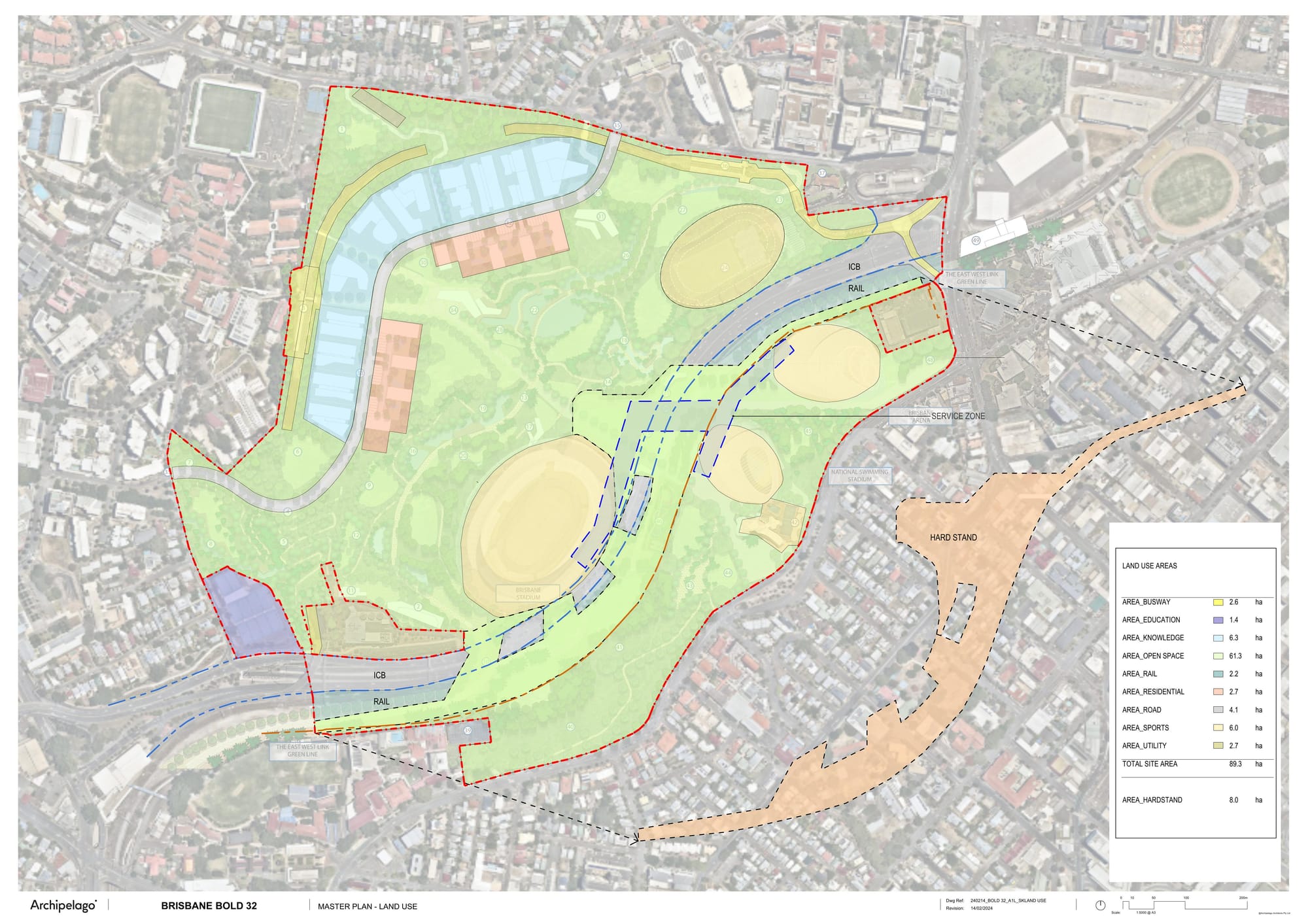

Archipelago’s proposal for the park includes a massive athletics stadium, a major swimming stadium, and Brisbane Arena (another big concert auditorium), as well as 6.3 hectares for commercial development (which they call a ‘knowledge precinct’) and 2.7 hectares of residential development.

(Amusingly, Archipelago also describe their vision as including 1.4 hectares at the edge of the park for ‘education,’ which when you look at the details is actually just ten open-air tennis courts that Brisbane Boys Grammar have managed to secure on a long-term lease from the city council – evidently the architects were fine with destroying trees and waterholes, but decided not to piss off the private school by proposing to build over their precious tennis courts)

Archipelago have spent thousands of dollars presenting and promoting this vision with interactive images and a lot of flowery language. But their spin glosses over a few significant concerns:

- it involves spending phenomenal amounts of money and resources building new sporting venues, rather than improving public transport connections to existing venues

- it involves a permanent, substantial loss of publicly owned green space

- it proposes selling off at least 9 hectares of the park for private commercial and residential development (in additional to the 6+ hectares of land that would be taken up by the stadiums)

Archipelago’s dubious claim that their alternative masterplan actually increases open space in the park is based on some very slippery logic and terminology...

Rather than comparing the land uses in their vision to the amount of actual green space in the park at present, they focus on the slightly more nebulous term ‘public open space.’

They say their masterplan would offer 61.3 hectares of ‘open space.’ But they downplay the fact that at least 8 hectares of this would be concrete ‘hardstand’ – not green space – built over the inner-city bypass and rail line.

In their comparison, they calculate that the council’s latest masterplan for the park (which many local residents have objected to) would only deliver 55.8 hectares of open space. This figure excludes the large and unnecessary open-air carpark the council wants to build, and the existing golf driving range which the LNP want to preserve.

The council’s proposal to formalise a massive carpark (roughly 3 hectares) on the north side of the park is idiotic for a range of reasons (even if it would also occasionally get used for market stalls and festival stages, as opposed to just car storage alone). But it’s self-servingly inconsistent that Archipelago don’t define the open-air hardstand carpark in the council’s masterplan as open space, but do include the 8 hectares of hardstand within their vision as part of their open space calculations.

Archipelago’s multi-billion-dollar proposal seems to constitute a net loss of roughly 15 hectares of the current publicly owned green space.

Comparing their masterplan to the council’s current plan, and arguing that their multi-billion dollar stadiums and privately developed ‘knowledge precinct’ buildings are superior to the council’s vision (with its giant carpark and golf driving range) is a classic example of the imaginative void I described above – ignoring all the other possibilities for a site that a given development proposal would effectively destroy.

Archipelago are suggesting we must choose between the council’s current suboptimal masterplan for Barrambin/Victoria Park or their vision (which carries an additional price tag of several billion dollars).

But what about all the other possibilities for Barrambin? Surely we can come up with a masterplan that makes the most of the park without selling off and building over big chunks of it – a vision that is led by First Nations owners, and imagines Barrambin as the vibrant, ecologically abundant beating heart of a forest city?

A few years ago, when the major parties took on my suggestion to shut down the Victoria Park golf course and open the site up as genuine public parkland, I was stoked but simultaneously suspicious: In a city that’s addicted to both construction and destruction, the property industry is always looking for new ways to enclose and develop public land. Even as we celebrated the opening up of the park, I worried that developers would start moving in.

But if Brisbanites can hold the line against Archipelago’s ill-considered vision for Barrambin, not only can we explore other, better possibilities for this huge inner-city green space – we can hopefully also start remedying our broader cultural addiction to endless construction and destruction.

Koalas at Barrambin?

When I started writing about Barrambin, I was tempted to outline my own broad vision for the site’s future – a green, non-profit counterpoint to Archipelago’s stadiums and commercial buildings, with densely vegetated wildlife habitat areas, useable public spaces for open-air festivals and events, communally-managed food forests and several hectares of urban farming plots.

But this is such an important cultural heritage site for Aboriginal people that I quickly reached an important conclusion: even presuming to articulate a detailed vision for its future was an inherently colonial act.

It’s not my place to dictate how Barrambin should evolve – that conversation must centre First Nations’ voices and aspirations.

But I do at least want to put one broad idea on the table for Jagera and Turrbal decision-makers to consider, so that Archipelago’s construction-destruction white elephant and the council’s current masterplan (dominated by carparking and a golfing range) aren’t the only possibilities deemed worthy of consideration…

We should consider converting a significant chunk of Barrambin/Victoria Park into an urban koala reserve.

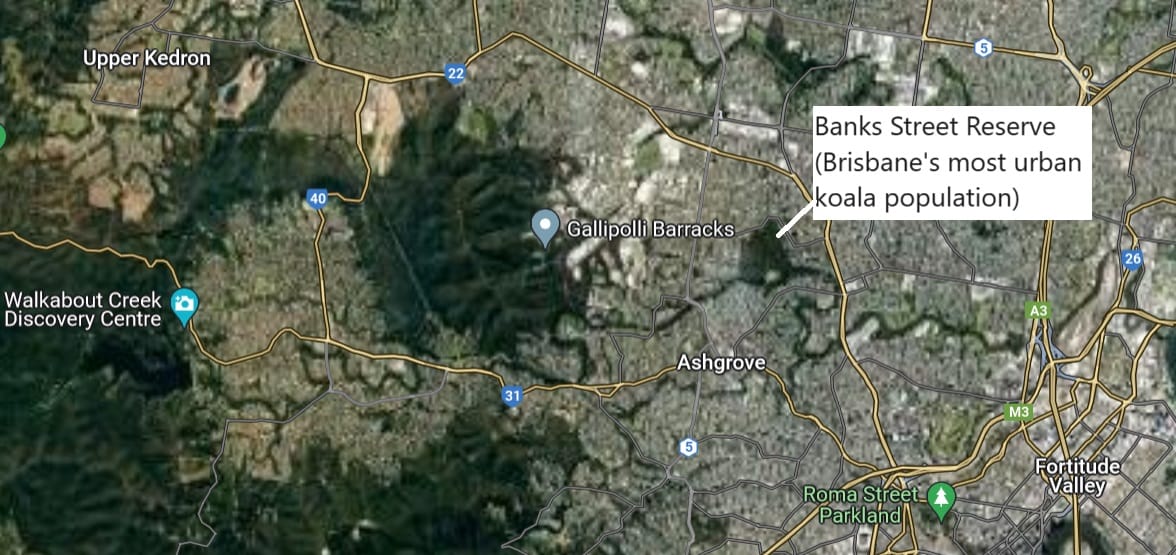

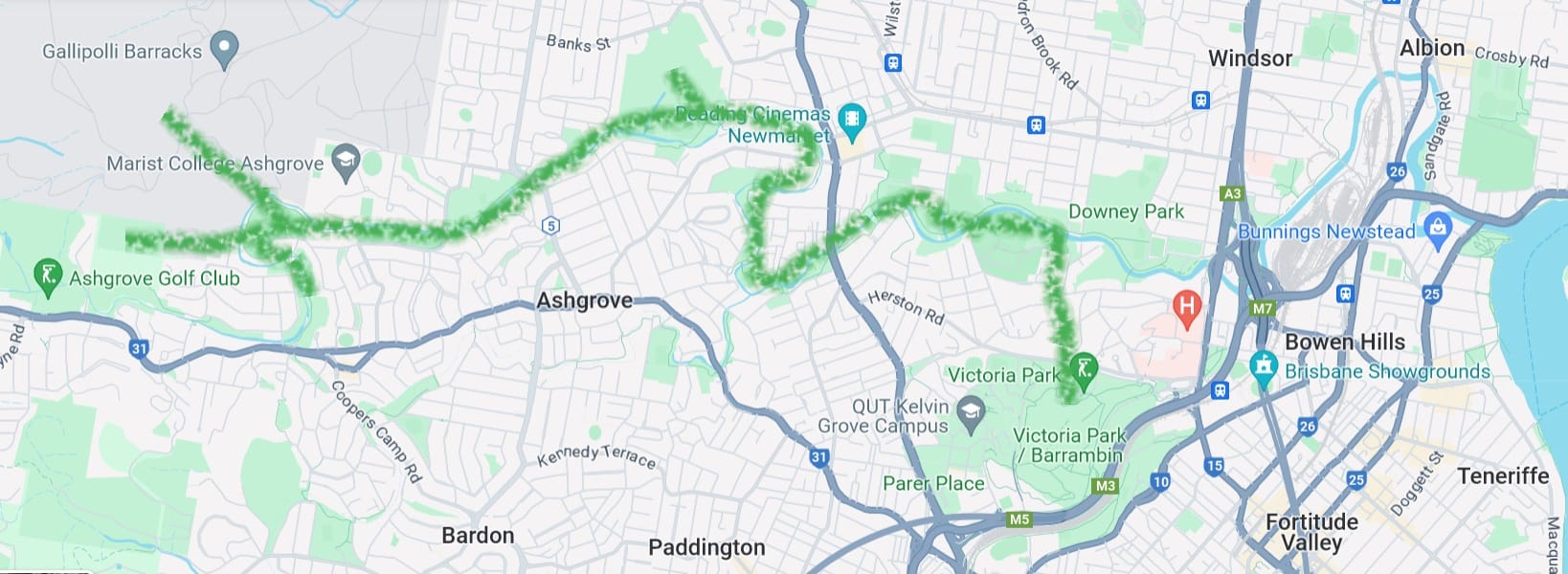

Barrambin is only a kilometre away from Enoggera Creek – a 33km wildlife corridor that flows all the way from Mt Nebo’s eastern slopes to the Maiwar River.

You can still find koalas living along Enoggera Creek in the 30-hectare Banks Street Reserve in Alderley, 3km to the northwest of Victoria Park.

It seems they may still be able to move along an increasingly fragmented wildlife corridor between the reserve and the larger Gallipoli Barracks forest to the west, connecting through to Mt Coot-tha and D'Aguilar National Park.

If Banks Street is cut off from other habitat nodes, this bushland reserve would be too small to support a genetically viable koala population long-term. But, if a significant proportion of Barrambin’s 64 hectares was reforested, and the wildlife corridor connections between Banks Street Reserve and Barrambin (via Enoggera Creek) were strengthened and protected, we could one day see koalas living here again, right next to the city centre.

With some additional reforestation work to the west of Banks Street Reserve around Frank Waters Park, Dorrington Park and Des Connor Park, and some lower speed limits on surrounding streets, a viable wildlife corridor capable of supporting the movement of koalas, sugar gliders and a host of other native species would extend from Mt Coot-tha and the D’Aguilar mountain range, all the way through the inner-northside to Fortitude Valley.

A corridor reforestation project of this nature would take up only a fraction of the resources Archipelago’s vision would require, while delivering a far greater positive legacy for the city. So why aren’t more of our city’s leaders talking about ideas like this?

Koalas do persist in several other bushland reserves around Brisbane's middle suburbs. Whites Hill is a major stronghold, with koalas spreading out into surrounding suburban parks and backyards, leading to growing concerns about car strikes. Their numbers in Toohey Forest also seem to have grown significantly since the late 1980s, when ecologists could find no evidence of koalas there (the population seems to have been re-established with individuals from Whites Hill),

Some of the southside bushland reserves where koalas are regularly found are even smaller than Banks Street. Weller Road Park (aka Wellers Hill) in Tarragindi, for example, is barely 4 hectares, and seems to host a few semi-permanent koala residents who've moved over from Toohey Forest. How many koalas a given green space can support isn't just a question of the reserve's physical size, but also depends on the health and diversity of the trees, and how much water they're getting.

As urban koala numbers grow in these other reserves, we'll need to find new green spaces to relocate them to, otherwise they'll keep roaming across suburbia, getting hit by cars or attacked by dogs as they seek out new territory.

Meanwhile, much of Barrambin's 64 hectares is currently open lawn, reflecting its recent usage as a golf course – there's enough space on these lawns to plant hundreds of eucalypts of varying species. A well-watered, densely-planted 20- to 30-hectare eucalypt forest in Barrambin, connected via the Enoggera Creek corridor to the existing breeding and foraging habitat in Banks Street Reserve, could support a healthy koala population, alongside a wide range of other native species (Christmas beetles anyone?) that are finding it increasingly difficult to survive within Brisbane's urban footprint. Politically speaking, the presence of an iconic native animal in Victoria Park would also help protect this public green space from future private sector proposals to sell it off or commercialise it, which will otherwise keep popping up every few years, even after the Olympics consumption orgy has wrapped up.

For koalas to thrive at Barrambin, you'd probably need to install extra fencing to discourage roaming males from wandering onto nearby arterial roads, but if the occasional koala found its way into the neighbouring Kelvin Grove university campus, I don't think anyone would be complaining. The local presence of koalas would also help build the broader case for transforming surrounding streets into low-speed, pedestrian-friendly environments rather than traffic sewers.

This isn't something that could happen overnight. It would take a couple decades for newly-planted eucalypt saplings to grow, and to re-establish a multi-layered native forest ecology. But Barrambin already contains quite a few mature eucalypts, so if we start planting more now, the first koalas could be moving in by the time Brisbane recovers from its inevitable post-Olympics slump.

Imagine all the positive flow-on effects of having a wild koala population living just 1.5km from the Fortitude Valley train station!

All in the name of ‘progress’

Olympics proponents and lobbyists from numerous sporting codes keep telling us Brisbane needs bigger stadiums and entertainment venues, pointing to major Sydney and Melbourne venues as evidence.

But for anyone asking why Brisbane doesn’t have anything like the 95 000-seat capacity of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, it’s important to remember that the statistical area known as Greater Melbourne, which covers 9,993 km2 (and which excludes the city of Geelong), has a population of more than 5.2 million residents.

In contrast, Greater Brisbane (which includes Ipswich, Logan, the Redlands, Caboolture, Woodford, the islands of Moreton Bay etc) and covers a much larger area of 15,842 km2, has a population of just 2.7 million.

Once you draw equivalent-sized boundaries, Melbourne’s actual metropolitan area has more than double the population of Brisbane, and the most recent available data suggests that in both raw numbers and as a proportion of total population, Melbourne is still growing slightly faster than Brisbane.

Any suggestion that we ‘need’ to have a similar size and number of major sporting venues as a city that’s more than twice our size is not just laughable – it’s fucking ridiculous.

In the past few centuries, in defiance of the examples set by so many Indigenous cultural traditions around the world, a poisonous delusion has spread across continents like a virus... This glitch in thinking – which narrowly defines ‘progress’ based on how tall and shiny the buildings are, how fast people can travel, and how many different kinds of non-essential products we are able to buy and consume – draws blind spots over the phenomena we most urgently need to attend to.

If Brisbane’s main function – its primary economic activity and the core preoccupation of its political and business leaders – was to simply ‘build more Brisbane,’ what would be the point of it?

Meanwhile, the private sector continually complains about narrowing profit margins, demanding more subsidies and regulatory relaxations from governments in order to remain profitable; the house of cards has begun to wobble.

One way or another, the construction-destruction spiral has to end eventually. If Brisbane plans for that shift, by deprioritising non-essential projects like stadiums and highways, putting all available resources into constructing public housing and retrofitting existing buildings rather than knocking them down altogether, we can perhaps avoid a more disastrous crash.

But the necessary policy changes aren’t likely to materialise until we start to change our city’s underlying culture.

For that to happen, every major construction project – particularly those proposed for the Olympics – must be subjected to far greater scrutiny, leading with the question: what is being destroyed in order for this proposal to proceed?

‘Progress’ can no longer be treated as an unassailable justification for every vanity project politicians or developers dream up.

At some point, we must find the courage to imagine a different future for our city – one where we can house a growing population and meet the community’s needs while replacing the construction-destruction machine with an ethic of balance and sustainability that restores rather than destroys native habitat.

Maybe restoring Barrambin as koala habitat won't be the priority for the land's rightful Aboriginal owners. But such ideas are at least an invitation for all of us to imagine something more than stadiums and parking lots, and to push back against the clowns who tell us such things are essential.

So what kind of city do we want Brisbane to become?

Thanks for reading! For those who are wondering, I don't share ideas like this without carefully researching them first. In raising the prospect of restoring Barrambin as koala habitat, I've spent time on the ground in Banks Street Reserve and walking along the Enoggera Creek corridor through Newmarket and Herston to understand the practical challenges of strengthening this wildlife corridor, as well as learning about the difficulties of managing other existing urban koala populations in places such as Whites Hill and Toohey Forest. Cutting through the spin behind Archipelago's Olympic proposal also required some diligent reading. My point here is that it takes a bit of work to produce commentary and analysis like this, so if you appreciate these articles being publicly available, please consider supporting my writing by signing up for a paid subscription, or at least sharing these ideas via social media so more people can connect with them.

Member discussion