Free camping as prefigurative rebellion

Night falls. The day trippers all seem to leave at once. Our rust-pocked 25-year-old Toyota with the too-narrow foam mattress in the back is the only vehicle left in the sprawling beachside carpark.

There are no council inspectors or security contractors coming to lock the public toilets. Outside the capital cities and a few coastal hotspots (e.g. Yeppoon and Emu Park in Livingstone Shire Council), local governments generally can't justify paying staff overtime or weekend rates to conduct patrols of every single beach and boat ramp. So the impotent 'No camping or overnight stays' signs mainly serve as a reminder that at some point in the past, someone sent their local councillor a complaint letter about people like us.

The reach of the surveillance state is not yet unlimited.

We are careful, of course, not to wear out our welcome. We take up as little space as possible, and don't leave our camp stove or folding chairs set up outside overnight.

We have an ethical commitment to leaving spaces better than we found them. I often pick up some rubbish that isn't ours, or pull out a few invasive weeds (unfortunately, too many travellers have a more extractive relationship to the places they pass through, focusing primarily on how much pleasure and value they can get out of a location while giving back as little as possible).

In the mornings, we wake to the arrival sounds of a couple of surfers or fishermen or dog-walkers, and open the curtains to an idyllic vista of waves crashing on a sandy beach.

These would once have been described as 'million dollar views,' but nowadays all a million dollars gets you is a view of other bland, bulky brick homes in the middle of suburbia. This carpark's views must be 'worth' $5 million at least.

We could stay at one of the 'official' caravan parks, but even their cheapest sites start at $50/night for 2 people in a campervan, which feels like a lot to pay for access to a hot shower when swimming in the ocean is still free. Many caravan parks are frequently booked out for weeks or months in advance anyway.

Australia used to have more low-cost coastal caravan parks, but many were sold off or redeveloped as beachfront mansions or luxury hotels. Sites that used to house 50 or 100 working-class holiday-makers are now occupied by just half a dozen rich families. That's capitalism for ya.

At busier free camping spots, there's a sense of community and camaraderie among travellers. We form connections. We share information, and sometimes food or equipment. I guess it's a form of commoning. Different car-sleepers negotiate with each other about where to park and how to share space, practising collaborative co-existence without anyone ever needing to call the cops to enforce their private property rights. It sometimes feels like the seedlings of a very different kind of society.

As someone who has argued strongly against the construction of new carparks on top of green spaces, I like seeing bitumen hardstand being repurposed for compact, non-profit housing. Given that the environmental damage has already been done, it feels like a far better use of space. This is prefigurative adaptation from below.

In a country that increasingly insists that only the mega-wealthy are entitled to water views, free-camping by a river or beach feels kinda subversive – a transgression... a rupturing of established norms...

Of course, what would be really subversive is if everyone in the world could afford to buy a campervan, take a month off work and watch the ocean all day.

On some level, I can understand why the rich feel so threatened and outraged by a couple of campervans in an under-utilised carpark (I say 'the rich' in general – I'm sure there are exceptions). If too many people were permitted to live in pleasant, scenic locations without the shackles of crushing rent and mortgage payments, this whole system might collapse.

The Liberal National Party's so-called 'politics of envy' actually operates in the opposite direction. You can see it in the resentment-drenched Courier Mail comments threads and the jealous undertone of the complaint letters to councils.

"We paid good money to live in this neighbourhood! Why should they get to stay here for free?"

These carparks are only ever full for a few weekends in summer, so right now our presence here inconveniences no-one, costs nothing. It doesn't materially impact them at all. They're simply jealous that we get to enjoy something similar to what they have, without paying as much as they did.

Drying off in the back of the camper after a midday swim, contemplating an afternoon nap to the sound of crashing waves, I find myself marvelling gratefully that simple luxuries of this kind are still possible.

Of course life on four wheels has its downsides. You're spending more of your days and evenings in the public sphere, so your life is on display. The lack of privacy, including being woken by garbage trucks or late-night rev-heads, starts to wear thin after a while. In wet weather, you're stuck inside your vehicle unless you have a nearby third space like a public library to retreat to. Even if you're in a larger vehicle with a good setup, you'll probably miss having daily hot showers, room to stretch out, and spaces to entertain friends.

Van life can be particularly rough for larger families with kids, or for those with chronic health conditions or severe disabilities. There are good reasons why most of us prefer living in purpose-built houses and apartments than caravans or motorhomes – why I love living on the road for a couple of months, but wouldn't want to do it forever.

But many of the biggest downsides actually spring from the way society discourages free camping. Itinerancy and disconnection from local community aren't an inevitable consequence of living a compact life in a vehicle – they're a consequence of feeling like you're not welcome to stay in the same spot for too long (this in turn becomes a barrier to getting to know the neighbours and building civic responsibility to care for the spaces you inhabit).

Car-sleeping on public land is technically illegal in many local government jurisdictions. But we're living through an interesting political juncture: More Australians – perhaps more than at any point in the colony's 250-year history – are sleeping in vehicles of one kind or another, without official approval.

Obviously there's a difference between those of us who are only on the road for a couple weeks or months and have somewhere else to return to, and those living in their car long-term, without any savings or family to fall back on. But these days it does also seem like the lines between #vanlife #nomad and "I'm just living on the road temporarily until I find an affordable rental" are increasingly blurry. People are still making choices, but their range of options has been narrowing.

The superannuated boomers with the massive $80k caravans and mortgage-free 4-bedders to go home to are perhaps in a distinct category, but even among the grey nomads you can find travelling pensioners who don't own anything other than their motorhomes, and who bounce between caravan parks, house-sits and their adult children's driveways.

Not everyone living in their vehicles long-term would consider themselves homeless, but the precarity is undeniable. We met one young woman in a Sunshine Coast carpark whose bedroom was an air mattress in the back of an old sedan. She was working as a cleaner, saving for a road trip to North Queensland, and said most nights she'd just sleep on a suburban street near whichever home she was scheduled to clean the next morning. Is she a free-wheeling traveller? Or an exploited member of the working poor? Or a bit of both?

All this unauthorised car-sleeping makes visible one of the great paradoxes of the so-called housing crisis (which is really just a subsidiary crisis of colonial-capitalism)...

Every city, town and beachside village has literally thousands of spots where you can legally park a vehicle for as long as you like, and even sit in it for hours reading a book or using your laptop, but where sleeping overnight risks a fine from the council.

So what's the point of that distinction? Whether a parked vehicle is empty or occupied, it takes up the same amount of space, and has more-or-less the same impact on other users of the park or beach or riverside road reserve.

An empty car or caravan or motorhome is fine, but living in it is a punishable offence?

Yes, it's not always clear where people living in vehicles will piss, shit and dispose of their rubbish, but that's hardly a justification for criminalising the mere act of sleeping in a vehicle that's safely parked. We already have plenty of specific rules against littering, leaving poop in silly places, and discharging unfiltered greywater into gutters.

In truth, it's always been about power and privilege – about maintaining a sense of scarcity of access to safe, well-located accommodation.

That's ultimately the main reason free camping is widely prohibited (even if those bans are only occasionally enforced). It threatens and destabilises the treatment of housing as a commodity, and would allow too many people to opt out of the rent trap and exploitative working conditions. In popular tourist destinations, it undermines the business models of for-profit hotels, Airbnb investors and caravan park operators.

If living in a vehicle on public land became a free, legal, practical option for those who were up for it, the downward pressure on real estate prices could be significant. If we had the backup option of moving into our campervans or caravans beside a local park or bushland reserve, without fear of being fined or moved on, many of us would feel more confident pushing back against landlord extortion.

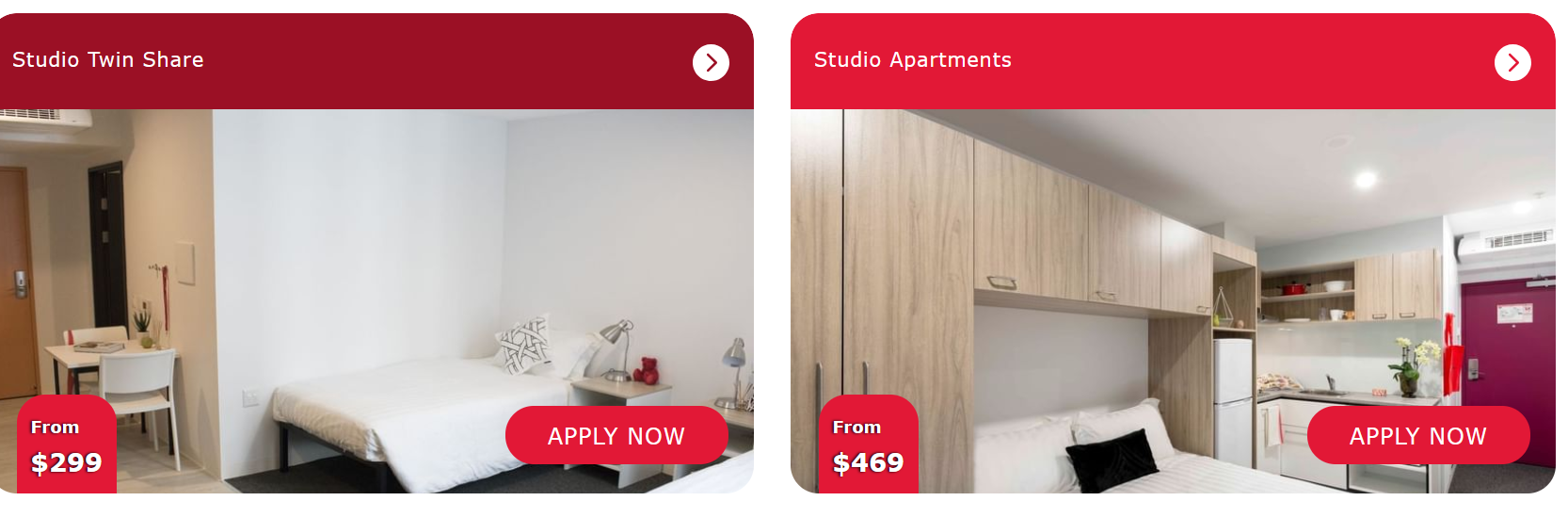

In Brisbane, Unilodge currently charges tafe and university students $469/week for an 18m2 studio apartment (that's smaller than some caravans).

How many students would tolerate such obscene rents if they could legally park up beside suburban green spaces a couple kilometres from campus, use all their uni's onsite facilities each day, and walk back to their vehicles to sleep?

Many tertiary students in South-East Queensland have already started doing this sort of thing. Even a decade ago, I knew one mate who camped out in a tent in Toohey Forest while studying at Griffith University (he wasn't a citizen at the time, and couldn't get youth allowance).

To be clear, I'm not arguing we should all move into campervans as a response to the housing crisis, or that it's desirable for a significant chunk of the population to live long-term in vehicles that weren't designed for it. But I do think there's a connection between the 'no camping or sleeping in your vehicle' rules and the housing stress so many people are experiencing.

Through hundreds of local laws and ordinances around the country, mayors and councillors have made free camping illegal in all but the most isolated locations. Privatised property is foundational to the Australian colony, and the idea that people should be able to live in a space without 'owning' it or paying rent is anathema to capitalism.

There's a lot more that could be said about how these rules enforcing transience actually create the main practical distinction between someone who enjoys living a compact, outdoorsy life with few material possessions, and someone who's 'homeless.' And you could write whole essays about how the restriction and criminalisation of unconventional housing responses is just one aspect of the continued dispossession and persecution of First Nations people.

What's increasingly clear at our current political juncture though, is that as more people begin free camping in their vehicles either out of choice or necessity, local authorities may well find it harder – both practically and politically – to enforce prohibitions.

Brisbane City Council, for example, seems to have more-or-less given up issuing fines for car sleeping (if anyone who knows someone in Brissie who has actually been fined for this offence in the past three years, please get in touch). Under pressure from my office (back when I was a city councillor), when BCC updated its Health, Safety and Amenity Local Law in 2021, the prohibition against 'camping on roads' (section 24) was watered down. It now includes exemptions allowing people to sleep overnight in a vehicle "where it is required for fatigue management, or for personal safety, or otherwise in emergent circumstances."

The more widespread and normalised free camping becomes, the safer it should be for the most marginalised and vulnerable members of society.

It's hard to predict exactly how governments will respond as housing precarity increases and more people adapt to informal and unconventional accommodation styles. Introducing timed or overnight parking restrictions at popular parking spots simply pushes people further into the suburbs and back-streets.

The contrast in Australia between obscenely high housing costs, and the fact that it's still mostly free to store vehicles on public roads (outside the busiest urban centres and beaches), seems like a tension point in the system that can't last forever. Something's gotta give eventually.

For now though, I'm gonna lie back and enjoy the view.

If you enjoy reading articles like this, please consider subscribing to my email newsletter. I send an update roughly once a month with links to my most recent pieces, and details of important community events and protests.

If you liked this piece, you should also check out my longer write-up about life on an off-grid houseboat.

Member discussion