On Being Doppelgangered

“You know, you’re nothing like what I thought,” the old bloke said, shaking my hand warmly, his gaze shifting repeatedly between my face and the photo of me on the flyer in his left hand.

“Oh yeah? What were you expecting?”

We’d been talking for a while, and I was wondering if I should be winding up the conversation. I could see a few other voters hovering nearby, waiting to say hi and ask me questions.

He shrugged sheepishly. “I dunno really. You’re just a lot more… normal?”

“You thought I’d be some crazed extremist screaming at everyone who walked past?” I said jocularly.

“Ha. Um… Yeah basically.” He seemed a tad bewildered. The real me was so strikingly different from the image he’d been carrying in his head, that I could see he was destabilised by the incongruity.

“Makes you think about the power of propaganda doesn’t it?” I offered.

He nodded. “Anyway, I should probably get on with this whole voting thing. Thanks for the chat.”

“So you think you might give us a go this time?” I asked.

“Yeah ok. I’ll vote for ya,” he said, and strode straight past the Labor and Liberal campaigners into the polling booth, with the Greens flyer in hand.

In the final weeks of my campaign for mayor of Brisbane City Council, I had dozens of interactions like this one.

Conversation after conversation – mostly with older voters – who expected me to be a divisive trouble-maker based on what they’d heard about me via social media, mainstream corporate media and printed materials in their mailbox, and were pleasantly surprised to meet the real me.

But depressingly, I also had plenty of interactions where people said things like “Not interested! I already know everything I need to know about you” despite never previously having met me or even read anything I’d written.

One middle-aged woman practically spat in my face when I tried to offer her a flyer, declaring “I would never talk to a fucking scumbag like you.”

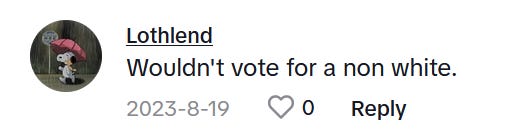

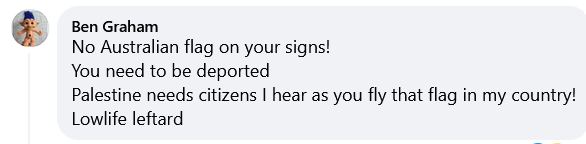

People had also become ruder on the internet. While I’ve always had a few trolls on my social media channels, the level of online vitriol had increased substantially in the final weeks before election day, with a particular spike in racist comments (mostly in my private inboxes).

See, by the end of the campaign period, there were actually two different Jonathan Sriranganathans running in the election…

There was the real Jonno, who worked for seven years as a city councillor, has an in-depth knowledge of housing policy and urban planning, and is geekily passionate about public and active transport.

And then there was a fictional doppelganger – ‘Sri the Divisive Extremist’ – who among other things apparently wanted to break into people’s homes, create traffic chaos, cut wheelie bin collections, jack up residents’ rates, and promote shoplifting.

Cloned (sort of)

Negative attack campaigns are common in Australian politics at state and federal levels. There are no rules requiring truth in political advertising, and our defamation law framework is understandably cautious about censoring what people can say or imply about candidates for public office.

But what happened in this local government election was much more intense, systematic and targeted than anything we’ve seen in Brisbane in recent years, particularly in a local government context.

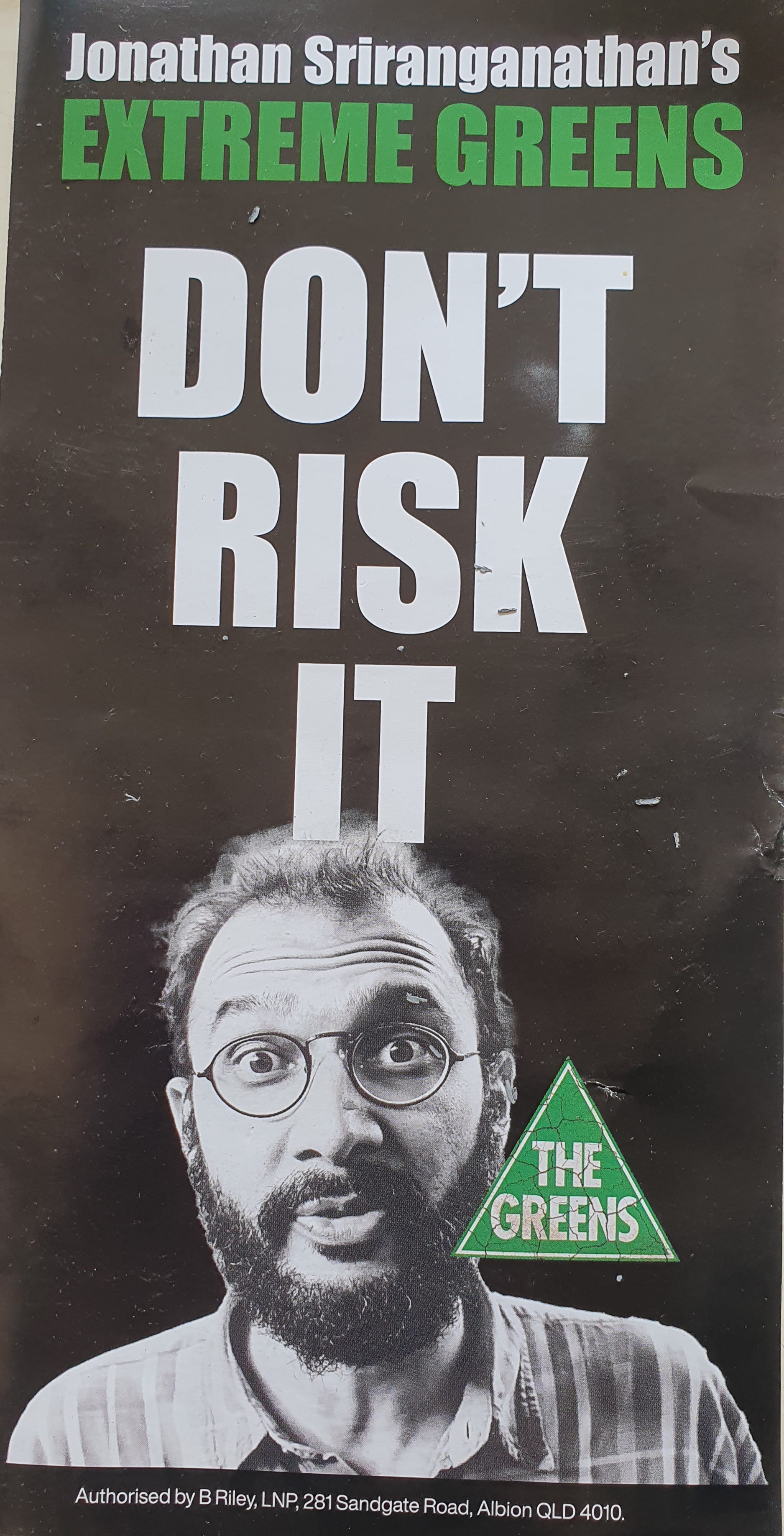

The Liberal National Party’s propaganda team essentially cloned my public identity, then used the clone as a political beating stick.

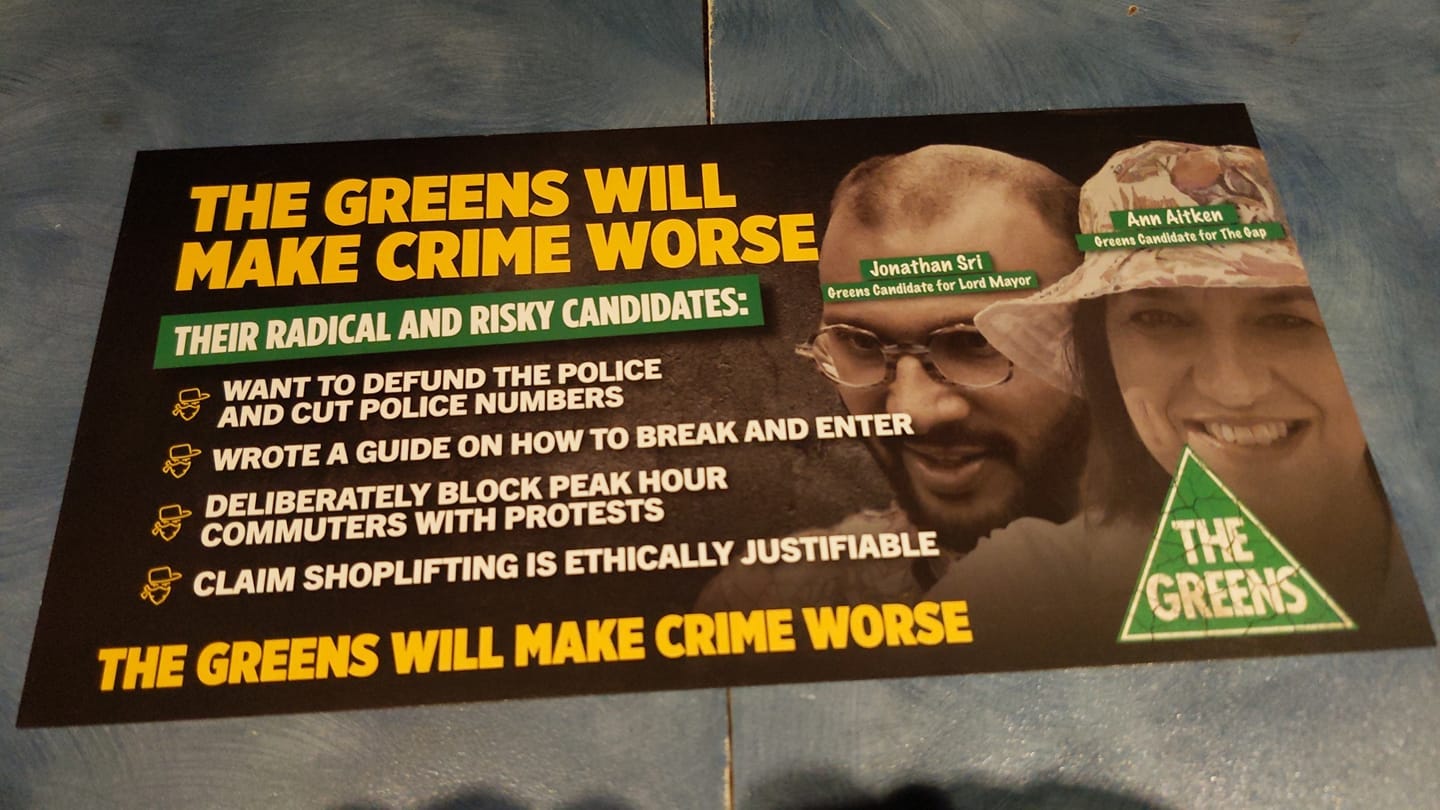

Like geneticists isolating fragments from a DNA sequence, they extracted elements of truth about what I stood for — that I was calling for big changes to the way our city is run… that I’ve said it’s ethically justifiable for people in desperate poverty to shoplift groceries from Coles and Woolworths... that I’ve previously supported various protest marches that temporarily blocked city streets. They then stripped those statements and actions from their original context, and recombined them into a virtual evil twin.

The LNP spin team created a new public image of me that had a ring of truth to it, but was so fundamentally different from who I actually am that when I saw the ads in my Facebook feed, I felt like I was watching a movie of someone else’s life.

Perhaps this wouldn’t have worked so well, if not for the fact that the council election propaganda war was entirely asymmetrical.

Incumbent elected representatives frequently come under attack from their political adversaries, but they also have their own large public platforms and communication budgets to counter the negative propaganda and at least contest the image their opponents try to craft.

But I wasn’t a premier or a prime minister.

I wasn’t even a serving city councillor anymore.

I was an unpaid candidate volunteering my time to run in a local council election on behalf of a comparatively cash-strapped minor political party that only held 1 out of the city’s 26 wards.

Outgunned

My campaign didn’t have anything close to the platform and resources the major parties could draw upon. What little money the Greens did have for the council election campaign mostly went straight into the key local wards we were trying to win.

This meant that for many of Brisbane’s 850 000 voters (at least, those outside the Gabba Ward, where I’d previously served as the local councillor for 7 years), the impressions they formed of me were based almost entirely on LNP advertising and spin.

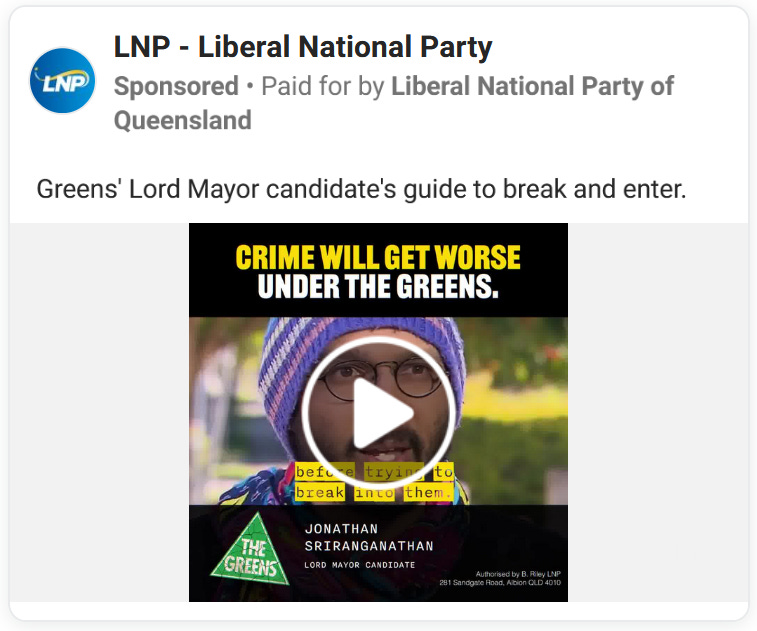

All up, the Liberal National Party’s 2024 city council campaign spent at least $2.7 million on election advertising and materials, from billboards to robocalls to flyers in the mail, including about $1 million on digital advertising alone.

In contrast, my mayoral campaign’s entire expenditure on digital advertising was just $7000, and total expenditure on signage and printed materials (including delivery costs in areas where we didn’t have enough volunteers) was a little over $40 000.

It’s hard to say exactly what proportion of the LNP’s budget was spent directly attacking me, but at a rough estimate, there were around half a million dollars’ worth of video ads, printed materials, coreflutes and billboards that included my name or face and portrayed me in a negative light.

The LNP didn’t create this doppelganger of me primarily to prevent more progressive voters from switching to the Greens, but to scare just enough swinging conservative voters into choosing the Liberals over Labor. And it seems to have worked.

The Queensland Greens were ill-equipped to deal with a multi-medium smear campaign of this scale and breadth.

Greens campaigners are generally trained to empathise and find common ground with the voter they’re talking to rather than challenging their views directly (even when that person’s views are bigoted or harmfully stupid), and a few Greens supporters accordingly responded to rising anti-Jonno sentiment by trying to distance themselves from me, which doesn’t work and didn’t help.

But I think most Greens staff and campaign organisers just didn’t grasp the extent of what was going on until the campaign’s final weeks, when we began to see the public disclosures of what the LNP were spending money on, the still-growing volume of anti-Greens/anti-Jonno attack flyers in the mail, and the ad transparency info that some socials platforms publish.

At first, we laughed at how ridiculous and hyperbolic the attacks were. People who’d actually worked closely with me and knew what I was really like found them completely uncompelling, and didn’t think they’d cut through.

But if you repeat a message often enough, via many different channels and formats, incorporating chopped-up out-of-context TV interview excerpts and misleading quotes from conservative newspaper headlines, the attacks begin to reinforce and legitimise each other.

The sheer weight of misinformation even begins to subconsciously influence people who’d normally be more sceptical of political propaganda.

To their credit, most journalists (I exclude certain 4BC radio shock-jocks from the umbrella of ‘journalist’) gave me a right of reply before broadcasting or publishing the major parties’ overt attacks against me. The direct damage came via online ads, billboards and printed material in voters’ letterboxes. But mainstream journos still fuelled the fire by regularly describing me as ‘controversial,’ ‘radical’ and sometimes ‘divisive,’ painting a general picture that the LNP spin team could easily embellish with more deliberate brushstrokes.

There was so much misinformation circulating about me across the city that by the time people actually met me, they felt like they already knew me, and that the real flesh-and-blood Jonno in their presence was the one trying to trick them.

By the final days of the campaign, I’d developed a radar for people who’d been sucked in by this spin. It was hard to miss the contemptuous sneers and the this-guy-seems-dangerous-I-hope-he-doesn’t-get-too-close-to-me hesitancy when I greeted them outside a polling booth.

If I introduced myself and the voter responded warily with “Oh yeah I already know who you are” one of my go-to lines (which, strangely, felt kinda like an admission of wrongdoing) became “Well I hope you don’t believe everything you’ve read about me in the media.” This often got a smile and a chuckle, but I doubt it was enough to neutralise their already-entrenched opinions of me.

In one conversation on election day, a woman even responded to this line with “Oh I definitely do believe it” and glared at me like she’d just caught me trying to jimmy open her bedroom window.

My Sri the Extremist clone was everywhere – simultaneously present in far more physical letterboxes and online spaces than I could ever hope to be. I was volunteering on the campaign upwards of 50 hours per week, but could still only reach a fraction of the people who were receiving multiple attack flyers in the mail and watching Youtube and Facebook ads suggesting I wanted to raise their rates and break into their homes.

All this was of course incredibly disempowering and destabilising at a personal level, but in the rush of the campaign, I didn’t even have time to pause and process what was happening to me.

See, as a city councillor who vocally challenged the neoliberal status quo, over the past 7 years I became accustomed – perhaps desensitised – to one-off clickbait media hit pieces and a certain proportion of the city’s population hating me.

That desensitisation meant I didn’t realise how much further-reaching this phenomenon was during the mayoral campaign. When the online trolling and negative in-person interactions started to increase in frequency, I didn’t notice at first, and certainly didn’t notice how it was affecting me.

Aftershock

Reflecting on it now, a few weeks after the election, I think one of the immediate effects was that I became unfeelingly dismissive of almost any criticism – whether reasonable or not – levelled against me by people I didn’t know (I suspect this happens to a lot of people in power who are subject to sustained public critique and scrutiny). I simultaneously became less willing to stand up for my views when people I did know disagreed with my ideas or said something negative about me.

Normally, I’m pretty confident about sticking up for myself and asserting my opinion, even in a room full of people with contrasting perspectives. But by the end of the campaign, I no longer had any appetite for tough debates with other Greens comrades about strategy and tactics, even when people were proposing approaches that I wasn’t particularly happy about. The drawn-out character assassination had worn me down and undermined my trust in my own judgement, and I began deferring to others more and more.

Perhaps on some level I even started to believe what the Liberal National Party propagandists were saying. Maybe they were right that I was controversial, inflammatory and extreme, and I should just lean into that?

In her excellent 2023 book, Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World, Naomi Klein writes: “confrontations with our doppelgangers inevitably raise existentially destabilising questions. Am I who I think I am, or am I who others perceive me to be?”

In the city I was born in, and had lived most of my life, tens of thousands of people I’d never met (and even a few who had known me personally) now believed I was a trouble-making extremist.

Commercial radio hosts with massive audiences were calling me a ‘dishonest grifter’ and a ‘menace,’ telling listeners I was a danger to society.

The president of the Queensland Jewish Board of Deputies publicly accused me of antisemitism and being “unashamedly, offensively racist” because of comments I’d made critiquing contemporary Zionism in the context of Israel’s genocidal invasion of Palestine.

Even the Labor party got in on the act, calling me a divisive attention-seeker and amplifying the Liberal National Party’s misinformation campaign against me (ultimately to their own party’s political detriment).

I’d completely lost control of my own reputation and how my neighbours perceived me.

To cope, I distanced my sense of myself from this twisted public image. The attack flyers, the billboards, the Facebook ads, and the rabble of trolls that gleefully recycled and amplified the LNP’s messages – that was all happening to some other guy named Jonno, not to me.

With press conferences to give and forums to prepare for, I simply pushed the feelings down into deeper mental crevices where I wouldn’t have to look at them. If fellow Greens campaigners asked me in passing how I was doing, all I had time for was a brief “yeah I’m fine” before rushing off to my next meeting.

It was only after the election was over that it all started hitting me.

My dentist said it looked like I’d recently started grinding my teeth in my sleep – a classic stress response. When friends texted to ask me how I was feeling about the campaign, I put off answering because I didn’t want to lie, and didn’t have the energy to tell them the truth. Even now, a month after the election, my heart rate starts to rise whenever I talk about or reflect deeply on the smear campaign.

Are doppelgangers immortal?

What stresses me the most is that my doppelganger seems likely to live on well past the election itself is forgotten. He’s still out there in the world, whispering doubt into the ears of future potential employers, shaping the perceptions of police officers and other power-holding public servants, and reminding trolls to post abusive and dismissive comments every time I share an opinion online.

It doesn’t really bother me too much if a bunch of privileged racists hate me. But the deeper problem with the kind of propaganda I’ve been the target of is that it can also subtly shape the attitudes of more progressive, politically engaged people who think they’re immune to it.

Even people who know better than to believe the LNP’s specific claims that I wanted to cut rubbish bin collections or jack up pet registration fees might still partially internalise the broader caricature of me as someone who is deliberately antagonistic and provocative.

As I’ve written about previously in the context of the smear campaign against Senator Lidia Thorpe, when you’ve heard that someone is prone to extreme ideas, or is controversial and combative by nature, you’re more likely to interpret whatever they say and do through that lens. Nuanced critique is experienced as bad-faith divisiveness. Serious suggestions are dismissed as impractical brain-farts. Bold, confident statements are interpreted as self-serving attention-seeking or pushiness.

Perhaps I’m over-estimating the impact of a few months’ worth of flyers and Facebook ads. I’m honestly not sure yet what ramifications all this will have for my relationships with activism comrades and Greens supporters more generally.

But I did hear about one Greens branch member who was so influenced by the attacks that he didn’t want to campaign for us in the council election. His impression of me had come almost entirely from corporate media reports and Liberal National Party spin, and like a lot of conservative voters, he’d decided I was ‘too extreme’ before he’d even met me. I doubt he was the only Greens volunteer who was turned against me in this way.

Propaganda is more powerful than most of us realise or admit.

The overt, specific messages mightn’t be taken too seriously by most sensible people, but a vaguer general vibe of trouble, disorder and uncertainty can still attach to an individual or political organisation, and seep into a community’s collective consciousness. This is particularly the case when a political attack taps into deeper prejudices that are already widely entrenched in society...

Yes, the LNP’s attacks were racist, even though they never explicitly mentioned race

Of all the different shades and consistencies of mud that the Liberal National Party threw at me over the course of the election, the claim that I advocated breaking into people’s homes seemed to be the stickiest.

The LNP experimented with a wide range of disingenuous attack lines – that I hated motorists, that I was antisemitic, that I opposed the construction of new housing etc. But the one they ultimately doubled down on and led with in their final bursts of digital and print advertising was that I had produced a ‘how to squat’ guide and was advocating breaking into people’s homes.

The basis of this extremely tenuous claim was that back in August 2022 I made a Facebook post explaining how census data could be used to identify which neighbourhoods had the most vacant homes in them (here’s some media coverage from the time).

For the record, in the current context of our government’s catastrophic, systemic failures on housing policy, I do think it’s ethically justifiable for people who are homeless to seek shelter in abandoned investment properties that have been left empty long-term. But that’s not the same as ‘producing a how-to-squat guide’ or advocating squatting as a holistic policy solution to the housing crisis (perhaps at some point I should produce such a guide just to stick it to them?).

Never ones to let the truth get in the way of winning an election, the LNP sliced up news coverage from 2022 along with footage from an older video I’d made about the need for a vacancy levy, to churn out this ad and many other similar ones of various lengths and formats with headings like “Crime will get worse under the Greens.”

Evaluated in isolation, it seems comical that any voter would take political attack ads of this nature seriously.

“Don’t vote for this guy cos he wants to break into your house! (Vote for us instead!)”

It’s farcical.

But of course, among certain demographics (particularly those that the Liberals were trying to win more votes among), the suggestion that unscrupulous people of colour might want to break into your home is considered entirely plausible. Such fears are routinely reinforced via nightly news reports and neighbourhood Facebook groups.

The spectre of someone – most likely imagined as a person with dark skin and scruffy facial hair – breaking into your house and stealing your stuff is very real for a lot of upper/middle-class Brisbanites.

Not only does it tap into ever-present dominant culture paranoia about migrant invasions, it stirs the muddy pools of deeper settler-colonial guilt about the squatting and violent dispossession that birthed the modern Australian nation state – “our forefathers squatted and stole Aboriginal people’s homes – we must be ever-vigilant against the same thing happening to us!”

An attack like that would never work against most political candidates. The LNP’s narrative that the first1 darker-skinned person ever to run for mayor of Brisbane was advocating breaking into people’s homes was only able to gain traction because on a deeper, subconscious level, a lot of voters were primed and ready to believe it.

It’s impossible to prove definitively, but I’d go so far as to suggest that if that kind of attack had been focused on a white Australian Greens candidate or other progressive commentator, the counter-reaction from progressive Brisbane circles would have been much stronger.2

The Greens’ primary strategic response to these attacks – ignore them and hope they didn’t cut through – might have worked against other messages, but a narrative that tapped into long-standing racist tropes was particularly potent among the target Labor-Liberal swing voter demographics that the LNP was aiming for.

More broadly, it seems like a lot of residents (and Greens organisers) who would consider themselves to be ‘progressive’ or who care a lot about social justice simply didn’t grasp or notice the racist subtext of attacks like this.

That’s how dog whistling often works - most of us don’t appreciate the hidden implications of what’s being said, but for people who’ve already been programmed to think a certain way, carefully chosen images and slogans can evoke strong emotional reactions.

Am I supposed to be a cautionary tale now?

For me personally, the experience of being doppelgangered has created a stronger urge to avoid online spaces and focus on the hyper-local – physical spaces close to my home where I can plant and nurture real seedlings, in-person community events and projects where people meet face-to-face.

I think I’ve become more cautious about publicly expressing my opinions on controversial topics because of the very real belief that a bunch of people who feel they know me (via my doppelganger) aren’t going to engage with those opinions seriously or respectfully.

A couple of times over the past few weeks, I’ve been on the verge of posting something online about how conservative political forces are weaponising ‘youth crime’ fears to distract us from the injustices of capitalism/colonialism, or about how federal Greens MPs are wrong to call publicly for big government subsidies for major for-profit music festivals (there are far more efficient and effective ways to direct public funds to support live music and the arts). But I just haven’t had the emotional energy.

Perhaps this will rebalance over time, and my appetite for posting spicy online opinions that generate wider constructive debate will return. For now though, the spectre of my virtual clone continues to make me doubt my own convictions.

My experience exemplifies one of the elite establishment’s most effective tools for disciplining those of us who seek deep change via electoral politics.

Concerted, well-resourced attacks on an individual’s character aren’t just about scaring that individual into silence or punishing them for challenging vested interests. They’re a warning to others.

I was made an example of so that other politicians and progressive commentators would feel more hesitant in future to express sympathy with low-income shoplifters or homeless people who squat abandoned investment properties.

Other Greens spokespeople – and in fact almost anyone in Brisbane who’s thinking about making public comment on important issues – will have watched what happened to me and taken note. They’ve seen how a few of my statements were cherrypicked, twisted, stripped of context and turned into attacks, and as a result, might be more likely to self-censor, refusing to say what needs to be said for fear that it hurts their reputation in the community and their election prospects.

I hope that’s not the case, and that those of us who seek a better world won’t be cowed into watering down the opinions they express publicly. But I’m definitely not the first person this has happened to.

When you look back through Australian political history, it becomes clear that people who engage with politics in order to make big changes are frequently co-opted and neutralised not by bribes and direct manipulation, but by relentless attacks (or threats of attacks) on their reputation that are intended to delegitimise anything they say.

A bigger pattern

For those craving a silver lining, I want to be able to tell you that at least things will be easier for others who come after me – that the next time a high-profile person of colour speaks up about systemic injustice, the hyperbolic personal attacks against their character won’t resonate as loudly. But recent history suggests otherwise.

Whether it’s Adam Goodes, Yassmin Abdel-Magied, Stan Grant, Randa Abdel-Fattah, Tarneen Onus Browne, Behrouz Boochani, Lidia Thorpe, Jenny Leong or Mehreen Faruqi, there are so many examples of prominent people of colour – and particularly First Nations people – who’ve been the subject of relentless and sustained political attacks after daring to stick their heads above the parapet.

Perhaps such a pattern points to the existence of another form of doppelganger who’s more deeply embedded in our society… Not a clone of any one individual, but a shapeshifter composite caricature of all racialised individuals who make political commentary that challenges the status quo.

Every time one of these real human beings (who are much more diplomatic, conciliatory and nuanced than cherrypicked public statements or actions might suggest) speaks up about injustice, people seeking to undermine them conjure a mutating doppelganger who takes on their identity.

The angry Black woman, the ungrateful immigrant, the divisive race-baiter… all these tropes merge into one target of opprobrium, and the racialised commentator or politician is blamed and resented not only for their own comments, but for every ‘divisive’ statement that any other person of colour may have made in the recent past.

Rather than blazing a trail for those who come after, each outspoken Aboriginal person or person with a non-European name or appearance exposes a fragment of their reputational DNA for this shapeshifting doppelganger to co-opt and feed upon.

We’re not talking here about mere stereotyping (although stereotypes are also part of the doppelganger’s DNA). This is something different – something so tangible and hefty that it’s capable of assuming a specific name and identity, can have statements and actions attributed to it, and that people can respond emotionally to in the same way they might interact with a real human.

Again, the writing of Naomi Klein feels relevant here:

“This is how prejudice works. The person holding it unconsciously creates a double of every person who is part of the despised group, and that twisted twin looms over all who meet the criteria, always threatening to swallow them up. Having one of these doubles means that whoever you are, whatever identity you have fashioned for yourself, however fresh and unique your personal brand, and however much you distinguish yourself from the stereotypes associated with your kind, for the hater you will always stand in as a representative of your despised group. You are not you; you are your ethnic/racial/religious double, and you can’t shake that double because you did not create it.”3

The ‘double’ in this case is not an ethnic or religious group as such, but a broader racialised category that applies to all non-white people who refuse to remain in the don’t-make-waves box that White Australia has assigned them to.

Perhaps this is why a few months of flyers, billboard messages and online ads were enough to manufacture a situation where random people felt compelled to verbally abuse me as they walked past me in King George Square (and while acknowledging that it might be a coincidence, I should point out that the only people who did this all presented as older white Australians).

Maybe the LNP didn’t create a doppelganger of me after all. They simply dragged up the generic ‘outspoken non-white provocateur’ doppelganger from whatever dark basement they keep it in and slapped my face on it.

I’m not sure it’s even possible to banish this older, larger changeling doppelganger without dismantling the ideological foundations of the Australian nation-state itself. Cops and soldiers need boogiemen to ‘protect’ us from, and the shapeshifter’s existence and persistence may in fact be integral to the broader project of settler colonialism.

Either way, the life we breathe into such doppelgangers has serious ramifications, not just for high-profile individuals, but for all racialised people, especially those most likely to be the target of police violence, militarised borders and invasive state surveillance. There’s a direct link between Aboriginal kids held in jail cells, refugees in offshore concentration camps, and the way we treat the people who speak up about such abuses.

It’s no longer possible for White Australia to completely silence and ignore well-informed critiques of settler-colonial capitalism. So instead, our society makes a doppelganger of the most prominent critics to string up as both punching bag and scarecrow.

Relying on individual champions of a movement to continually speak up until they stumble under the weight of abuse is asking them to carry an impossibly heavy burden.

If the rest of us stay silent, we let the doppelganger and its masters win.

Hi! Thanks for reading. If you value this kind of writing and commentary, please consider becoming a subscriber to support me to keep doing it...

Looking back through 200+ years of historical election records, it seems (unsurprisingly) that every single mayor of Brisbane City Council and the preceding Brisbane Municipal Council was white. As far as I’ve been able to ascertain, I was the first person of colour ever to run for mayor. It’s possible that at some point in the past there were unsuccessful independent or minor party candidates for mayor with non-European heritage, but I haven’t been able to find any evidence of them. If you have any insights to shed on this, please email me at office@jonathansri.com ↩

It’s interesting to note that while he has definitely still copped significant criticism, the recent responses from the Australian commentariat to Jordan van de Berg’s (aka Purplepingers) endorsement of squatting seem to have been less vitriolic and hateful (although I imagine they would have been stronger and shriller if he were actually running as a political candidate). ↩

Naomi Klein, Doppelganger — Chapter 14: ‘The Unshakable Ethnic Double.’ ↩

Member discussion