Cyclone time: Capitalism and river mud on the streets of Brissie

Time in South-East Queensland has felt kinda slippery this past week.

Uneven.

Non-linear.

Cyclone Alfred didn’t respect the simplistic build-up > climax > recovery narrative arcs that disaster movies have trained us to expect...

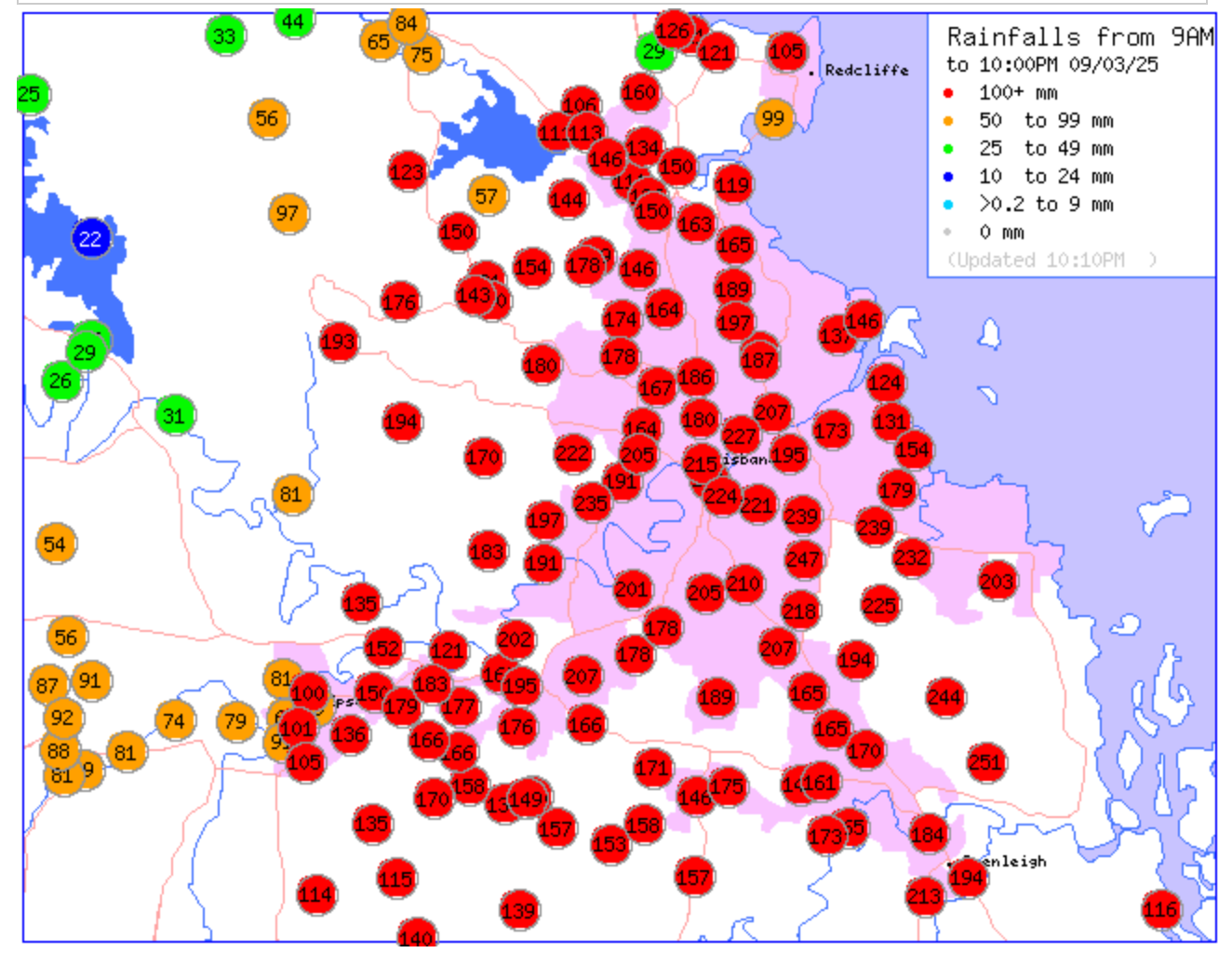

The long wait to see if the ocean-bound weather system would turn west and head back towards the coast... A frantic rush on Wednesday to secure homes as the wind picked up, then an unexpected extra day of waiting while the cyclone stalled at sea… The dissonance of watching the Gold Coast and Northern Rivers get smashed while much of Brisbane and the Sunny Coast enjoyed clear skies…

It wasn’t until after people started posting rants about media sensationalism and “was that it?” memes that the damaging winds and flooding rains finally hit the capital itself. Was the cyclone sentient and malicious? Did it intentionally lure us into a false sense of security?

Alfred stirred up a muddy swirl of contradictions and deficiencies in how our culture responds to unnatural climate disasters.

Even as journalists and political leaders were telling us we should be evacuating flood zones, stocking up on supplies, or preparing homes for destructive winds, bosses, bankers and landlords were still pressuring us to go to work (rents and mortgage repayments generally aren't paused during a disaster). The political class hasn't yet properly acknowledged this contradiction.

For many floods and cyclones, the stress and damage could be reduced significantly if more people got more time off work beforehand to get ready. But the capitalist machine insists on churning for as long as possible.

Instead of clocking off early to collect sandbags and move clean, undamaged furniture to higher ground, a lot of people – especially lower-income, working-class residents – must wait until after the disaster strikes and work is cancelled, then move their muddy, damaged furniture to the kerbside for rubbish collection.

When flood warnings are sent out multiple times each summer, even those who do have slightly more work flexibility face tricky choices regarding how much disaster prep to do.

“I hope all this isn’t for nothing,” one floodprone neighbour remarked to me, while carrying boxes of possessions upstairs, as though having spent all that time and effort, it would now be worse if the cyclone didn’t hit.

Call a public holiday ya bastards!

I don’t think the Premier ever really issued a clear “no more business as usual, everybody stay home and get ready” directive.

Wednesday's announcement that school, public transport services and elective surgeries would be cancelled from Thursday, 6 March partly served this purpose. But the government at the time was expecting the cyclone to hit land on Thursday. Only Alfred's unexpected slowdown east of the bay islands allowed Thursday to become an extra prep day for some parts of the region.

On Monday, with many roads still cut, and new, major flood warnings being issued for the Bremer River and Lockyer Valley, Ipswich residents were already being pressured to get back to work.

Capitalist time and cyclone time simply aren’t compatible.

If further severe storms materialise next week or next month, will we repeat this whole weird dance all over again?

For politicians intent on minimising impacts to business profits, these kinds of time-fluid disasters are extremely inconvenient.

Maybe they should’ve just declared a couple of public holidays and told the corporate sector to cop the lost revenue or higher wage bills. But it all gets very messy when commercial landlords still insist on collecting their rent, small businesses can’t afford to lose half a week of trade, and no-one's entirely sure which jobs are ‘essential’ in a disaster.

As usual, the most precarious workers get the rough end of the pineapple. In the private sector, leave entitlements for unnatural disasters are murky at best, especially when it’s unclear exactly where, when and how hard a cyclone will hit. And a casual supermarket or service station employee has no way of knowing in advance whether post-disaster support payments will materialise to help them cover their bills if they turn down a couple shifts.

It seems we've been lying to ourselves: We've built a world that assumes the climate will be stable and consistent, while pumping enough pollution into the air to destabilise it irreversibly. Our schedules demand a fixed, predictable number of weekdays and holidays, with 40 weeks of school each year, 38 hours of work per week, and so little wiggle room that even a half-day of phone network outages can throw the whole city out of wack.

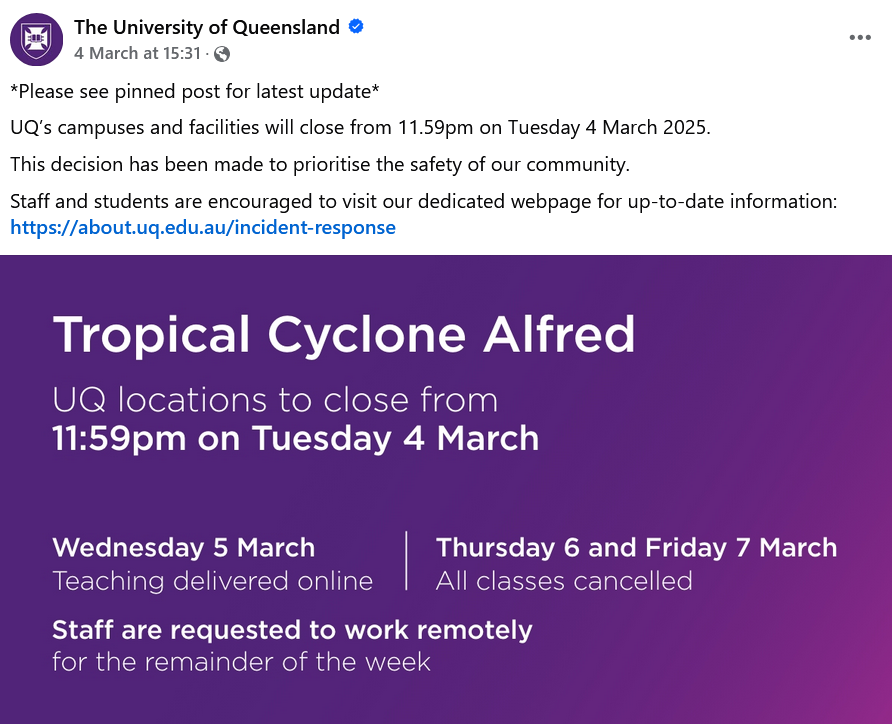

On Monday evening, QUT made the call that all its campuses would be closed from Wednesday onwards, whereas UQ and Griffith Uni took until Tuesday afternoon to announce the same decision

In some parts of the world, where monsoonal storm disruptions are frequent, societies build in more flexibility. Business owners open up shop when the weather is fine, and stay home to catch up on domestic work or spend time with family when the storms roll in.

Pre-invasion Aboriginal cultures didn't keep working as the cyclones approached – they sheltered on high ground and told stories around the fire until the danger had passed.

But here and now, between precarious just-in-time supply chains, back-to-back deadlines, and business models that can't absorb more than a few days' per year of disruption, most organisations and companies simply don't have enough slack and resilience. They can't handle severe storms cutting roads and internet connections, or even influenza outbreaks that send half their staff onto sick leave.

It's clear our systems are too rigid.

Spare time = community care

Sometimes I have the misfortune of conversing with people who oppose raising the dole above the poverty line, or investing more in public housing. In debates with stonehearts of this kind, you almost inevitably encounter some variation of the argument that if the majority of humans aren’t forced to work to pay for housing, food and healthcare, they won’t do any productive work at all, and society will supposedly collapse under the weight of everyone’s selfishness and laziness.

But just like Brisbane’s 2011 and 2022 floods, the past week has definitively undermined such arguments.

As their ordinary work obligations and other commitments were progressively cancelled, more and more people started volunteering many hours a day to help strangers, with no expectation of payment or direct reciprocation. This will continue during cleanups, until people feel obliged to return to their normal work. Spending a day (or two or three) in the wind and rain filling sandbags for strangers, when you could be at home sipping hot chocolate, defies several of capitalism’s core justificatory myths.

Greens volunteers in particular turned out in large numbers across the city to fill sandbags for people they'd never met

It turns out that even without financial compensation, a lot of people can and will undertake socially useful work if their immediate basic needs are met and they have the time to do so.

In fact, South-East Queensland is incapable of recovering from major climate disasters without thousands of hours of voluntary work by residents, just as capitalism cannot function without the millions of hours of unpaid reproductive work required to grow children into workers, or the many volunteer-based organisations that plug the gaps in our frayed social safety net.

Cyclone Alfred’s temporal vagaries briefly liberated a lot of people – particularly able-bodied younger adults – from paid work. And rather than going home, or finding a muddy slope to boogie board down (no judgement – that’s cool too), they chose physically demanding unpaid work to help their community.

But many of the sandbag depot volunteers didn’t actually have full-time jobs to begin with. They were part of a large, essential cohort of residents who only do paid work part-time. These people choose to prioritise having more time for social relationships, hobbies, activism and unpaid community work, over higher levels of material consumption and bigger, more expensive homes. As our city faces a future of more frequent, severe weather events, we need to get better at theorising and valuing the existence of people who eschew full-time work, but whose unpaid work is essential to keep society functioning.

No time for full-time in an apocalypse

In an increasingly atomised society, balancing full-time work alongside household chores and so-called life admin is already tricky enough. Add in all the extra work and stress of prepping for increasingly frequent severe weather, supply chain disruptions, and whatever else the polycrisis throws at us, and it feels like many of us will either be losing a social life or a lot of sleep on an ongoing basis.

Consequently, more people are choosing to consume less, and contenting ourselves with cheaper housing (generally smaller or more crowded) in order to avoid full-time paid work obligations. In doing so, we free up time for community organising, relationship maintenance, thinking and learning about important issues and, when a flood is predicted, for checking in on elderly neighbours or filling sandbags for those still working full-time.

I’m not downplaying the reality that lots of people have to work full-time just to make ends meet. I’m simply suggesting that the current, normative work-life balance (I still hate that term) simply won’t be compatible with joyful, sustainable lives amid a worsening climate crisis.

The fact that suggestions of stopping business-as-usual paid work for a few days before and after major disasters actually attracts pushback from some workers shows just how broken the system is. If thousands of people – especially self-employed contractors – feel they need to keep working to pay their bills even as a literal cyclone is blowing into town is damning evidence against capitalist modernity.

This isn't so much about the individual choices people make in terms of full-time vs part-time paid work arrangements. It's about the need for all of us to collectively demand a rethink of the traditional 40-hour work week, and of everything else that would have to change to make shorter work weeks possible.

If politicians are feeling they can't encourage people to close up shop and stay home for half a week during major disasters, because the economic impacts will be too severe, that's a clear signal that our current system is woefully ill-adapted to an increasingly volatile climate.

Capitalism has never been able to account for the reproductive labour – overwhelmingly undertaken by women – that’s required to sustain this broken system. As new forms of unpaid labour become increasingly necessary to prepare for and recover from unnatural climate disasters, the tension will only increase.

The brief ruptures – when flood warnings proliferate, storm clouds gather, and cancelled work shifts suddenly create more free time out of nowhere – highlight both the latent contradictions, and the alternative possibilities.

Global warming isn’t going to care about distinctions between weekdays and weekends, or how many billable hours you’ve worked since the last disaster. But how people actually choose to use their time when a cyclone disrupts business-as-usual gives us important clues about the better world we can work towards as the dominant order's foundations erode and wash away.

River mud takes a lot longer to clean once it’s dry.

I hope you found this piece thought-provoking. Finding the time to explore and flesh out ideas like this is difficult (especially when I still need to make repairs to some storm damage on my boat). Special shout-out of gratitude to my partner Anna for chatting, thinking through and refining these ideas with me. If you want to support me to write more regularly, please consider signing up for a $1/week paid subscription.

Give this one a read too if you haven't seen it already...

Member discussion