Could Brisbane bring back Christmas beetle swarms?

My friend’s kids don’t know what Christmas beetles are.

I explain how, not so very long ago, they would swarm suburbia in their millions: fat, shiny, yellow-orange scarabs kamikaze-ing our faces, tangling in our hair, thunking off windows, playing marco polo in the dog’s water bowl, relentlessly infiltrating our homes to alert us that summer was here...

To these kids, my earnest stories about squadrons of iridescent flying jewels from the grassy woodlands beyond the suburban horizon sound comically exaggerated.

Beyond their suburban horizon, there’s just more suburbia.

They think I'm making it up.

Of the 35+ different Christmas beetle species, I think the most common in South-East Queensland are (or were) Anoplognathus porosus and Anoplognathus pallidicollis.

They’ve been emerging annually for tens of thousands of years before European settlers invaded – presumably a significant marker in Murri calendars. Given their huge numbers, I imagine the larvae might even have been a seasonal protein source for local mob (if you know of any First Nations stories relating to the beetles, please email me).

I recall the ones we saw as kids mostly being bright orange with a metallic green shine.

Growing up in West Chermside – in Brisbane’s northern suburbs – in the 1990s and early 2000s, Christmas beetles were so numerous during the warmer months that they could become a genuine nuisance. They’d stick to your clothes, or thwack into you during a backyard cricket game like tiny ballistic missiles. If you left the screen door open, you’d get half a dozen of them in the kitchen, buzzing along the window sills or circling a light bulb for hours before dropping onto your dining table.

I remember how they’d invade our primary school classrooms, bringing disruption and mirth by freaking out the newly-arrived international students. During lunch breaks, more mischievous classmates would catch them and slip them down the shirt collars of unsuspecting victims.

They were a reliable, seemingly-eternal feature of the city’s seasonal cycles, recurring predictably each summer. The first golden emissaries appeared a month or so after the last Ekka showbag lollies had been devoured, and bigger numbers took to the air as jacarandas blossomed and summer storm clouds began rolling in.

I guess I assumed that’s how it would always be. But their numbers were diminishing each year. By the time I graduated high school and started uni, we’d be lucky to see a mere handful all summer. Nowadays, Christmas is heralded not by the beetles themselves, but by the almost-cliche annual news reports remarking on their absence.

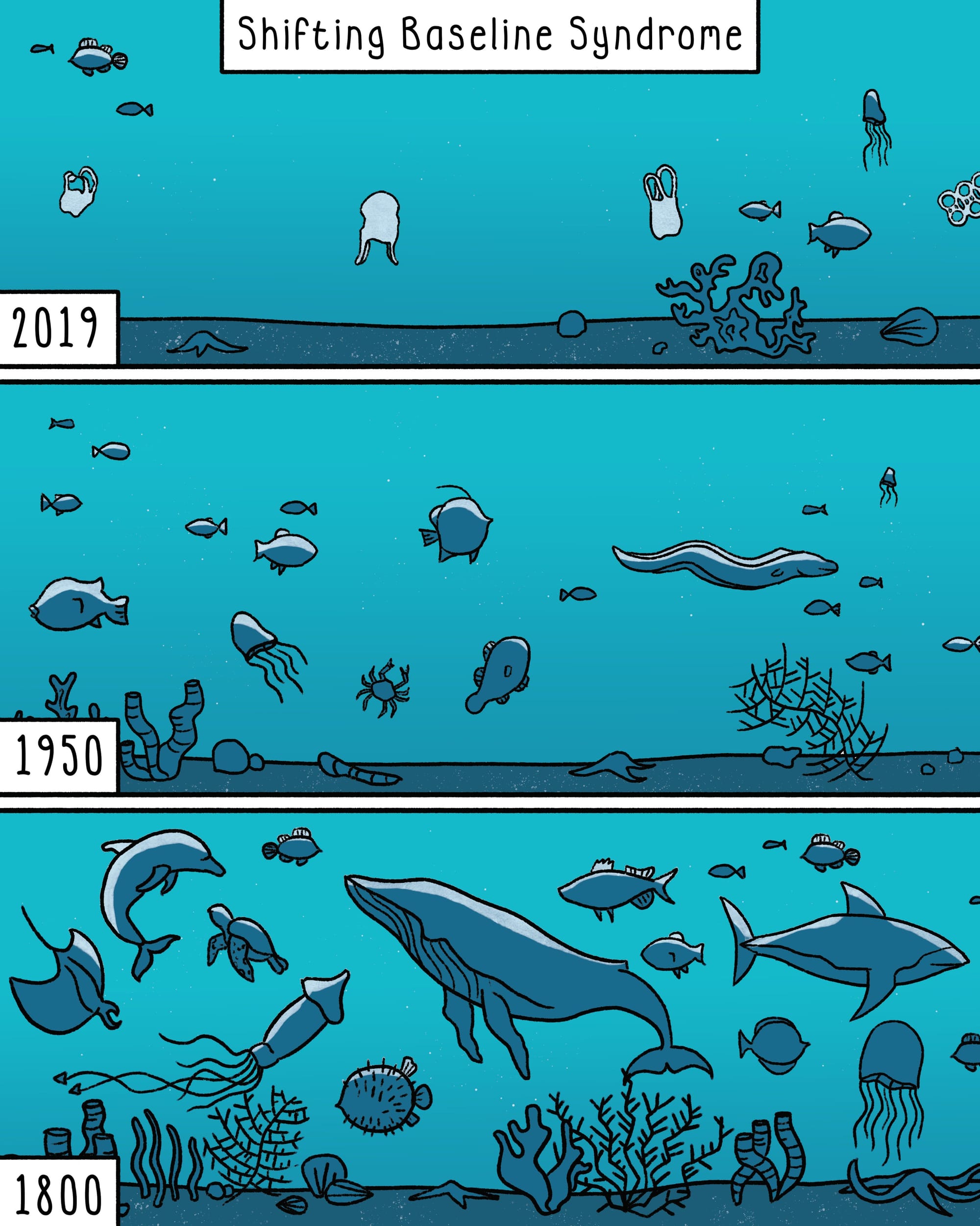

In the 1990s, fisheries scientist Daniel Pauly popularised the term ‘shifting baseline syndrome.’ This concept highlights how the greater quantity and diversity of wildlife we experienced in our youth is often mischaracterised as a highwater mark, when in fact the ecosystems we recall from our childhoods were already degraded and diminished.

My mum grew up in the same part of Brisbane as I did, and remembers there being far more Christmas beetles during her childhood than mine. There would likely have been even more again when her mother and father were young, but they've passed away; our family has no direct generational memory of that time, and there’s no hard data (in the Western scientific sense) to refer back to.

The ecological abundance of just half a century ago already feels like an impossible fairytale.

Part of what made Christmas beetles so cool – and perhaps why every social media post about them elicits so many enthusiastic, nostalgic responses – is how ostentatiously they ruptured the false boundary between ‘nature’ and our suburban built environments. In an era that often fetishised sterile building designs that sealed out the non-human world, where many of us felt trapped under fluorescent lights in air-conditioned offices, there was something delightfully subversive about thousands of shiny beetles taking over our backyards without permission.

“You can’t fence out the ecosystem!” the insects buzzed defiantly, flying straight over the new six-foot Colorbond steel barriers and the ‘Private property – keep out’ signs that were spreading across suburbia.

Beetles don’t respect property boundaries. They couldn’t give a toss about intercoms, surveillance cameras or the Neighbourhood Watch.

But of course, the war we’d declared on their habitats did have casualties.

The sharp decline in Christmas beetle numbers is part of a troubling global collapse in the populations of thousands of different insect species. Insects are integral to almost every terrestrial food web. No-one’s quite sure what happens if all the creatures that pollinate our crops, decompose animal faeces and carcasses, or serve as food for so many other birds, reptiles, fish and mammals, disappear altogether.

"What, though, if we don't act quickly enough? If the fall of insects' tiny empires causes whole ecosystems to unravel, toppling previously solid certainties about the way our world functions, what then?"

- Oliver Millman, 'The Insect Crisis'

I’m sure some Brisbane residents don’t mind that there are fewer insects around the Maiwar Valley than there used to be. But that also means less food for larger animal species, and diminished food webs that are slower at decomposing plant and animal matter to return nutrients to the soil. It means poorer tree health, and less biomass moving uphill and inland to counteract long-term gravity-fed flows of organic matter from the mountains down to the coast.

Eventually, it could mean complete breakdown of ecosystem equilibriums, characterised by pendulum swings between plagues and population collapses, and in only a few decades, the inability to grow any kind of food crop that depends upon pollination by wild insects.

We need to reverse this trajectory.

If we want to regenerate degraded landscapes and support more resilient ecosystems, we have to care about the smallest players in the nutrient cycle.

Turning it around

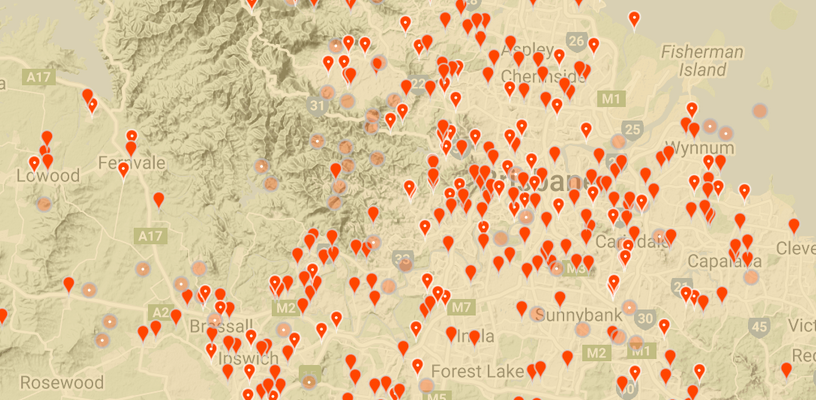

The thing is, it probably wouldn’t be that hard to get Christmas beetle numbers trending in the opposite direction if we act now. Citizen scientist reports on iNaturalist suggest there are still viable breeding populations within Brisbane's urban footprint.

Christmas beetle populations seem to have crashed around Brissie partly because we’ve chopped down so many of the mature eucalyptus trees whose leaves the adults feed on, but also because the rotting tree logs and native grassland environments that Christmas beetle larvae grow in have been replaced by suburban sprawl housing developments and parking lots. The reckless poisoning of suburban lawns to indiscriminately eradicate so-called ‘lawn grubs’ (i.e. beetle larvae) hasn’t helped either, and light pollution is likely also a significant factor.

Recreating more habitat for Christmas beetles would also mean more habitat (and more food) for many other vertebrates and invertebrates. Perhaps most importantly, it means a greater cycling and transfer of nutrients to the areas where they’re most needed.

There are plenty of spots around our city – from road verges to parks to private backyards to those under-used areas at the back corners of schools, hospital grounds and sporting precincts – that could serve as habitat. Common lawn grasses could be left to grow long, or even replaced with native grasses that are more Christmas beetle-friendly. Planting more native grasses, and more eucalypts for adult beetles to feed on, is a reasonably straightforward proposition, as is ceasing the use of toxic herbicides and pesticides that kill native insect larvae.

If we want our kids to see swarms of Christmas beetles every summer like we used to, we could make it happen. It might take a few decades, but it is possible. The same is true for many other butterfly, moth, beetle, grasshopper, cricket and cicada species that were once abundant in the Maiwar Valley.

Growing public consciousness about declining insect populations has spurred projects like Brisbane’s Pollinator Link initiative, which encourages residents to plant more insect-friendly vegetation in yards and verge gardens. Brisbane also has heaps of bushcare and creek catchment groups that more of us could volunteer with to help restore public green spaces.

We can (and should) be pressuring Brisbane City Council to support more areas of public parkland to transition from short-cropped lawn back to long-grassed eucalypt woodlands. But we could also try to influence the future of other sites that aren't directly controlled by the council...

Many of us are connected to a workplace, school, religious organisation or sports club that controls patches of land which are rarely used by humans, but which the organisation still spends money mowing on a regular basis. So take a moment to learn how the entity you’re connected to makes decisions about site management, then go along to a committee meeting, or talk to whoever manages the space, and ask if they can just let the grass keep growing.

It’s all connected

If at this point you’re thinking, “Jonno that’s all well and good, but urban Christmas beetle populations don’t seem quite as important right now as say, genocide, or mass homelessness, or apocalyptic planet-wide climate change!” you’re right – sort of.

But ultimately all these catastrophes are inter-connected consequences of individualistic, short-sighted ways of thinking and relating to the world around us. To rectify the big stuff, we also need to pay attention to small things – especially insects – because system change requires cultural change.

Our dominant culture under capitalist colonialism teaches us not to care about phenomena like declining Christmas beetle populations. So to acknowledge that they do matter is a potent act of resistance – a rejection of the relentless pressure to consume unsustainably and think only of our own enrichment.

Rewilding pockets of Brisbane to create more insect-friendly habitat doesn’t ask very much of us: plant a few more eucalypts, reduce pesticide use, switch off non-essential outdoor lighting, leave dead wood to rot on the ground, stop mowing the rarely-used corners of parks and school grounds... It wouldn’t require us to divert time or energy away from other parts of the struggle for a better world.

But it would help to shift aspects of our culture – to prompt us to attend to the many forgotten cycles and webs that we depend upon for survival. It would offer coming generations a reminder that there are no hard boundaries between ‘the city’ and ‘nature,’ subverting colonial myths of human self-sufficiency and separation from the biosphere.

Regenerating Christmas beetle habitat is an invitation to critique settler-colonial myths about dominating and ‘taming’ the land – to listen to First Nations voices calling for deeper socio-cultural transformation, and perhaps even to learn from the beetles themselves about the shallow arbitrariness of distinctions between ‘public’ bushland reserves and ‘private’ yards.

At a time of so much loss, proving it’s not too late to reverse insect population declines also feels important for counteracting disempowering narratives about the inevitability of apocalypse.

At the very least though, we need to recall and re-narrate the stories of how different things were in our city just a few decades ago, so that our imaginations of what’s possible don’t shrink as generational memory fades.

Most of us in this city are lucky enough to have experienced something approaching ecological abundance in our own lifetimes. Surely it’s worth striving to restore that?

Decades from now, I don’t want to be telling stories about how there used to be way more Christmas beetles around when I was young.

I want to be talking about how we brought them (and ourselves) back from the brink.

Oh hi! Thanks for reading. If you liked this piece, please consider sharing it on social media. And if you'd like to support me to write more stuff like this, it would be amazing if you signed up for a $1/week paid subscription to my monthly newsletter...

Member discussion