Why is Brisbane City Council intentionally preventing bunya pines from producing nuts?

We live in a strange time and culture. So many of us crave a greater connection to natural ecosystems, but the world we’ve curated for ourselves is so mindlessly, ruthlessly hostile to life’s rhythms and cycles.

In Musgrave Park, a green island within so-called Brisbane’s rapidly developing inner-southside, a smattering of half a dozen bunya pines stretch above the park’s figs, tuckeroos, palms and bottle trees.

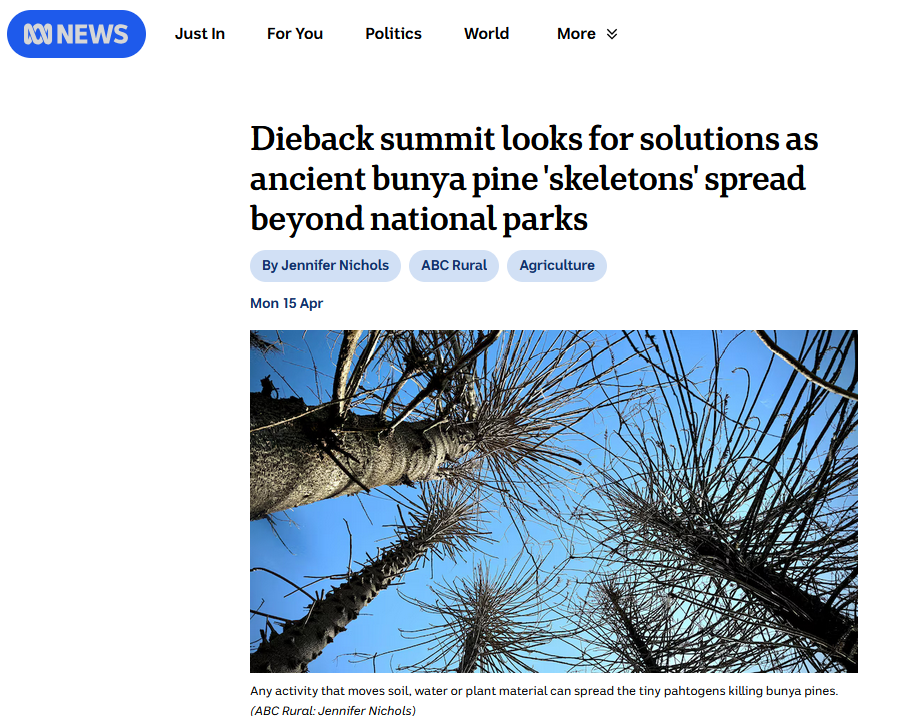

Bunyas (Araucaria bidwillii, more properly called ‘bonyi-bonyi’) produce huge, rugby ball-sized seed cones containing up to a hundred edible nuts. Almost all bunya pines yield a bumper crop every three years, and some trees also produce smaller crops annually or biannually.

They first evolved at least 100 million years ago, and their seeds were likely spread by herbivorous dinosaurs. The seed cones are too heavy to move very far by themselves, so without larger reptiles or mammals to carry their nuts long distances, the pines take a long time to spread.

For tens of thousands of years, their nourishing bounty made them a central element of south-east Queensland Aboriginal culture, with thousands of people gathering for major harvest festivals in the Bunya Mountains.

But the natural rhythms of Musgrave Park’s bunya pines have been short-circuited.

During my time as a city councillor, I was surprised to learn that on a regular basis, a crane is brought into the park, and a couple of tree management contractors climb into the canopy of each pine, systematically removing the flowers and emerging seed heads from each bunya, one by one, to stop them producing nuts.

This ‘denutting’ practice continues today at a recurring cost to Brisbane City Council of several thousand dollars for Musgrave Park alone, with similar costly measures in many other council-controlled spaces where bunya pines grow (if anyone has more details on how many parks and streets the council does this in or the total cost, please email me at office@jonathansri.com). It turns out this is actually standard practice in lots of public parks and gardens around Australia.

Why does the council spend so much money preventing Brisbane’s bunyas from producing nuts, foreclosing any chance of renewing ancient harvesting practices?

“Health and safety.”

The hypothetical risk of a bunya nut cone falling on and injuring a park user sitting under a pine’s canopy is considered too high.

When I asked if we could instead put up warning signs or even temporary fences every three years (a far cheaper and simpler option than cranes and highly-paid contractors), I was told that wasn’t sufficient to mitigate the risk, and that people might ignore the signs and still sit or stand under the trees.

When I asked if we could plant denser, shrubby gardens under these trees to discourage people from hanging out in the bunya nut drop zone, I was told that wouldn’t comply with the planting guidelines that applied to this kind of park.

Apparently it was just easier to spend thousands of dollars bringing in cranes to stop these trees ever reproducing.

In late 2016, when we created a small new park at the corner of Thomas Street and Vulture Street in West End, the late Uncle Sam Watson named the space ‘Bunyapa’ (‘place of bunya’). This was a nod to the history of South-East Queensland’s bunya nut festivals, and reflected the park’s intended function as a gathering place and hub of community celebration. The council ultimately declined to plant an actual bunya pine in the park, opting instead for other tree species which wouldn’t drop large nuts.

Bunya nuts aren't cheap

If you’re trying to buy them from a retailer, harvested bunya nuts currently sell for upwards of $45/kg. Larger cones can contain a couple kilos of nuts, so if the council didn’t interfere, the Musgrave Park trees could potentially produce several thousand dollars’ worth of nutritious, high-protein nuts each cycle. Instead, Brisbane spends thousands of dollars stopping them.

For me as a city councillor, this was a minor gripe in the grand scheme of things. With poorer residents being evicted, mega-projects destroying entire urban green spaces, and low-lying neighbourhoods increasingly at risk of flooding, getting into long arguments with LNP councillors and council officers about this simply wasn’t a good use of my time, and I let it go.

But every time I visit Musgrave Park, I think about those trees, and what it says about our city that we can’t be bothered accommodating the reproductive cycles of a species that first appeared at the time of the dinosaurs, and has been a major source of nourishment for local Aboriginal people for tens of thousands of years.

Araucaria bidwillii isn’t on Brisbane City Council’s standard planting lists for parks and street trees. That means new bunya pines are only very occasionally planted in any of BCC’s thousands of public parks (unless individual residents engage in some guerilla gardening). And as Queensland houses get bigger and backyards get smaller, there’s no space for bunya pines on private properties.

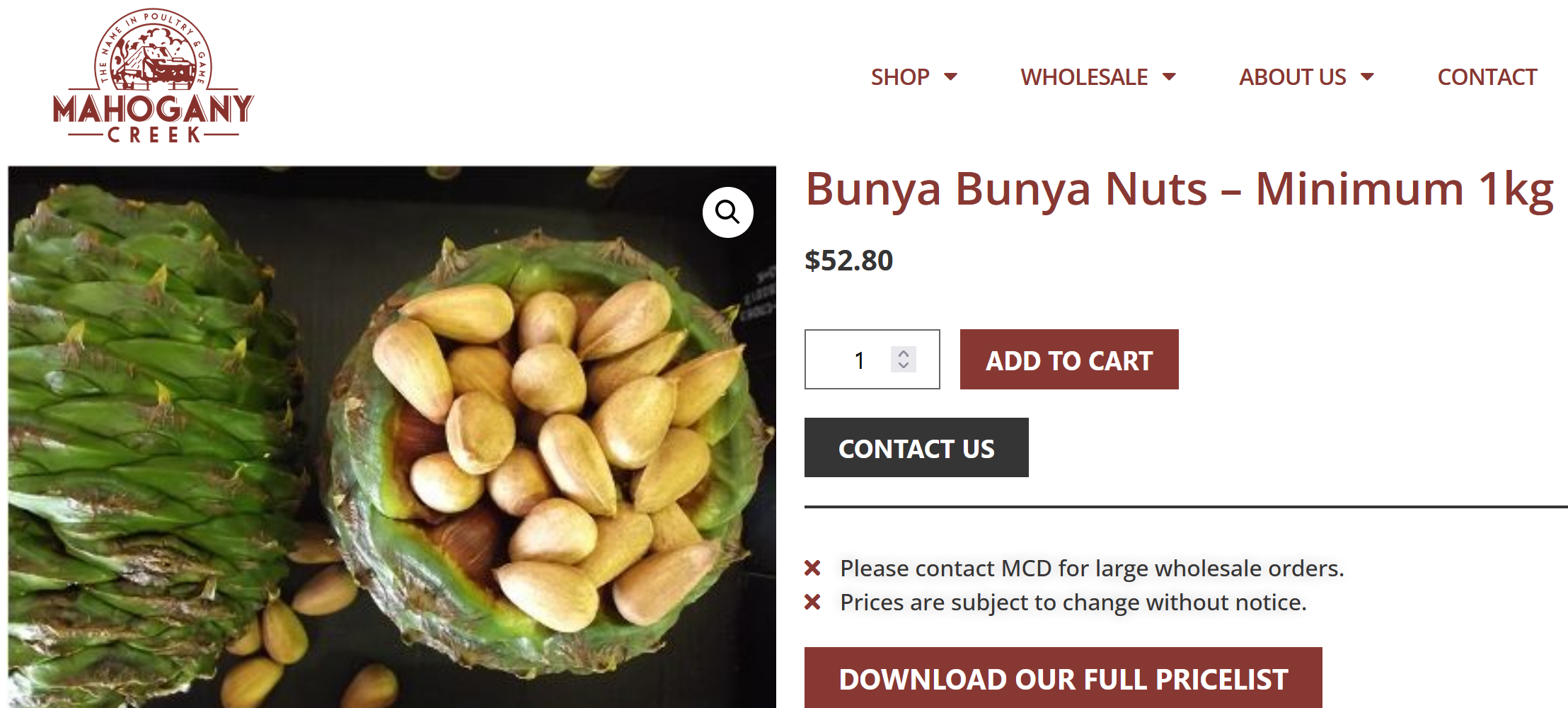

Meanwhile, Bunya Pines growing in National Parks and bushland reserves across their native range are now dying off in large numbers due to the increasing pressure capitalism is placing on their environment.

Their numbers will continue to shrink unless humans make a conscious effort to plant new ones.

As far as I've been able to ascertain, no-one anywhere on earth has ever been killed by a falling bunya nut cone. Despite thousands of bunya pines growing in parks and botanic gardens around the world, I could find only two reported examples of injuries from falling bunya cones – a close shave for a couple in New Zealand, and a more serious one in San Francisco (a very unlucky guy who was actually sleeping under a tree reportedly suffered brain damage).

More common are stories like this one from Tasmania, about a 170-year-old bunya pine that was cut down after it apparently dropped cones on some cars. I guess destroying a tree that’s older than the Australian nation-state was easier than asking motorists to park somewhere else.

When you compare the risk of falling nuts (which, remember, mostly only fall for a few months in late summer/early Autumn, once every three years) to all the other things that frequently kill or injure people, from car crashes to slipping over in the bathroom to excessive alcohol consumption, the council’s costly denutting missions seem an absurd over-reaction.

A modern city contains myriad genuine threats to human health and safety, many of which government authorities put little to no resources towards mitigating, but it’s the natural processes of a native tree (and important local food source) that end up being targeted.

Why do we over-estimate the risk posed by trees, and consistently under-rate the dangers of cars, or junk food, or forever chemicals? Could it maybe have something to do with the undemocratic pressure that corporations exert over government decision-making?

I'm not suggesting there is no risk of falling bunya nuts causing injury. But the risk is extremely low. It reflects poorly on dominant Australian cultural attitudes to the environment that local authorities can't be arsed finding alternative ways to manage this risk that would still allow the trees to reproduce.

This isn’t really just about a few bunya pines in one urban park (don’t even get me started on the council’s war on gum trees!). It’s about our inherently colonial, adversarial relationship with the natural world.

What are we normalising when we accept practices like this as necessary?

And what connections with our local environment are we depriving ourselves of?

Will there be any room left for bunya pines to grow and reproduce in South-East Queensland’s rapidly-expanding conurbation?

I publish a couple articles each month about green politics, local culture and the future of our city. To support this writing, and ensure you get updated about my latest pieces, please sign up for a paid subscription to my monthly newsletter.

Member discussion