Breakfast Creek does not exist(?)

When I go to write about Breakfast Creek, I don’t sit near the famous Breakfast Creek Hotel. The heavily-concreted public space along the northern bank is devoid of shade, and blighted by the ugly Mercedes-Benz mega-showroom on the opposite shore.

Nor do I gravitate towards the overly-manicured colonial lawns of Newstead Park, with its expansive views of the bend where creek meets river, and fishermen search vainly with their hooks for a glimpse of life beneath the surface.

Instead, I’m drawn a few hundred metres upstream, past Argyle Street and the creek’s last boat builders, to Yowoggera Park – the coolest, shadiest spot along the waterway’s lower reaches – with its figs, tuckeroos, poincianas and mangroves.

Like so many creek-side green spaces, this park feels like a forgotten secret – a green refuge in a busy, built-up city – worlds away from the surrounding noisy roads that feed the six-lane arterial (formally an Aboriginal walking track) heading northeast towards the airport.

The mangrove veil softens the glare of sunlight bouncing off the creek’s surface.

The tide is rising now, so the water is flowing inland.

White ibis browse the creek bank. Butcher birds call from the tree canopy. A blue-grey striated heron, hard to spot among the mangroves, inches its way along a low-hanging branch just above the water’s surface, moving in slow motion to avoid spooking the fish. As I watch, it darts into the water with a small splash, but returns to the branch empty-beaked.

It’s late morning on a Sunday, blustery and partly overcast, neither too hot nor too cool.

Most inner-city, waterfront parks would be busy on days like this, but Yowoggera is almost empty of humans, except for the occasional group launching kayaks or jetskis from the boat ramp at the park’s northern end. One reason for this is that there are few residential homes within easy walking distance. Southern Albion is extremely flood-prone, and is still zoned (for now) for industrial land uses (despite developers regularly lobbying for the precinct to be rezoned for highrise towers); the nearest streets are dominated by car yards and warehouses.

Brisbane City Council has installed a children’s playground and an unusually large picnic shelter with five picnic tables and two barbeques, while neglecting to provide a public toilet, making it an inconvenient location for any kind of party or gathering.

But perhaps the overarching reason so few people hang out here is that even on a windy day, the midges swarming up from the narrow strip of intertidal mudflats are vicious. While I sit writing, a middle-aged couple bring a takeaway lunch down to the picnic shelter. They comment on how beautiful this spot is, but don’t linger long – the biting midges are too aggressive.

The insects keep me on edge too as I write. I have to shift position every few minutes, swatting at my exposed ankles and wrists. It’s like this place doesn’t want me to feel too settled and relaxed, which makes sense when you think about its history…

Even the name is contested

The funny thing about so-called Breakfast Creek is that despite being a relatively well-known city landmark, it’s not really a creek in its own right.

The waterway most Brisbanites know as Brekkie Creek is simply the lowest reach – the last 1.5 kilometres or so – of Enoggera Creek, which has its origins far to the west on Mt Nebo, at the edge of the D’Aguilar Range, and winds almost 34 kilometres through Brisbane’s western and inner-northern suburbs before it joins Maiwar. The exact point at which Enoggera Creek becomes Breakfast Creek has been the subject of vigorous, largely pointless debate over the past two centuries.

Sitting in Yowoggera Park, I’m struck by the strangeness of a creek that’s known by one name of Aboriginal origin for most of its journey down from the mountains, but by another, English name for its last leg when it reaches the city. Perhaps Breakfast Creek doesn’t really exist at all?

Sources vary on whether Yowoggera (also Yawagara) was one of the names for the creek itself, or for a specific corroboree place beside the creek, or indeed for the broader area stretching out through the present-day suburb of Albion. Several early maps spelled it as ‘Euoggeru Creek’ or ‘Euoggera Creek’ but careless readers – including, apparently, some officials in Sydney – mistook the first ‘U’ for an ‘N,’ changing the creek (and suburb) name to Enoggera.

The first gunshot

Considering its history, the name ‘Breakfast’ is deceptively innocuous.

The most common, least interesting version of the name’s origin story is that the surveyor John Oxley stopped overnight and had breakfast there on his second expedition up the river in 1824, while mapping the landscape and scouting potential locations for the future Moreton Bay penal colony.

But there’s much more to it. In his field notes from Thursday, 16 September, 1824, Oxley writes:

“Fine, pleasant weather. Left the brig, accompanied by Lieut. Butler and Mr. Cunningham, with two boats, to complete the survey of the river. At four arrived at the head of Sea Reach, when we stopped for the night. We had scarce pitched the tent when we were visited by a party of the natives, the seniors of which were very troublesome, endeavouring to steal everything they could lay their fingers on; at dark we were relieved from their company.”

On Friday, 17 September, the day of the immortalised breakfast, he notes:

“The same party of natives visited us again this morning as we were embarking. I had put my hat, barometer, and surveying instruments on a rock close to the boat, and surrounded by the people who were getting the baggage into the boat, when two of the natives were discovered making off with the above articles. They were pursued, but, as they gained on us, Mr Butler fired at the man who had the instruments, which caused him to drop them, being, I suspect, struck by some of the shot. The other fellow got clear off with my hat. We pursued our course up the river, which we did not find fresh so low down as in the former voyage. The botany of the brushes, etc., was entirely tropical. [...]”

Reading these words almost exactly 200 years later, I’m struck by how casually and succinctly Oxley describes this violent incident before moving on to other observations from the day. Of course expedition journals are often concise, but this is one of the most significant moments in the city’s recent pre-history. You’d think it’d be worth more than a couple sentences.

Here we have a group of European invaders scouting and preparing the groundwork for the violent theft of an entire, heavily-populated river valley. After repeatedly helping themselves to the bounty of the country without asking permission from local Aboriginal residents, they decide that shooting a man is a reasonable response to the taking of a hat and barometer.

British navigator Matthew Flinders was probably the first European to shoot at Aboriginal people in the Moreton Bay region, firing on members of the Djindubari clan in 1799 at the southern end of Yarun/Bribie Island, which he accordingly named ‘Skirmish Point.’

The Flinders incursion is the only record of gun violence until Oxley’s arrival. Absent any preceding journal reports of expedition members opening fire at locals either on Oxley’s 1824 voyage, or during his first trip up the river in December 1823, it seems Enoggera/Breakfast Creek may be the location of the very first time European invaders shot at an Aboriginal person in the vicinity of the Maiwar River and the future city.

This is where South-East Queensland’s Frontier War began.

If Enoggera Creek really does need a second, European name, a more fitting option might be ‘Invasion Creek.’

Within a decade of Lieutenant James Butler firing that first shot beside the creek, it would become a crucial battlefront at the northern edge of the expanding colonial township.

‘Numerously inhabited’

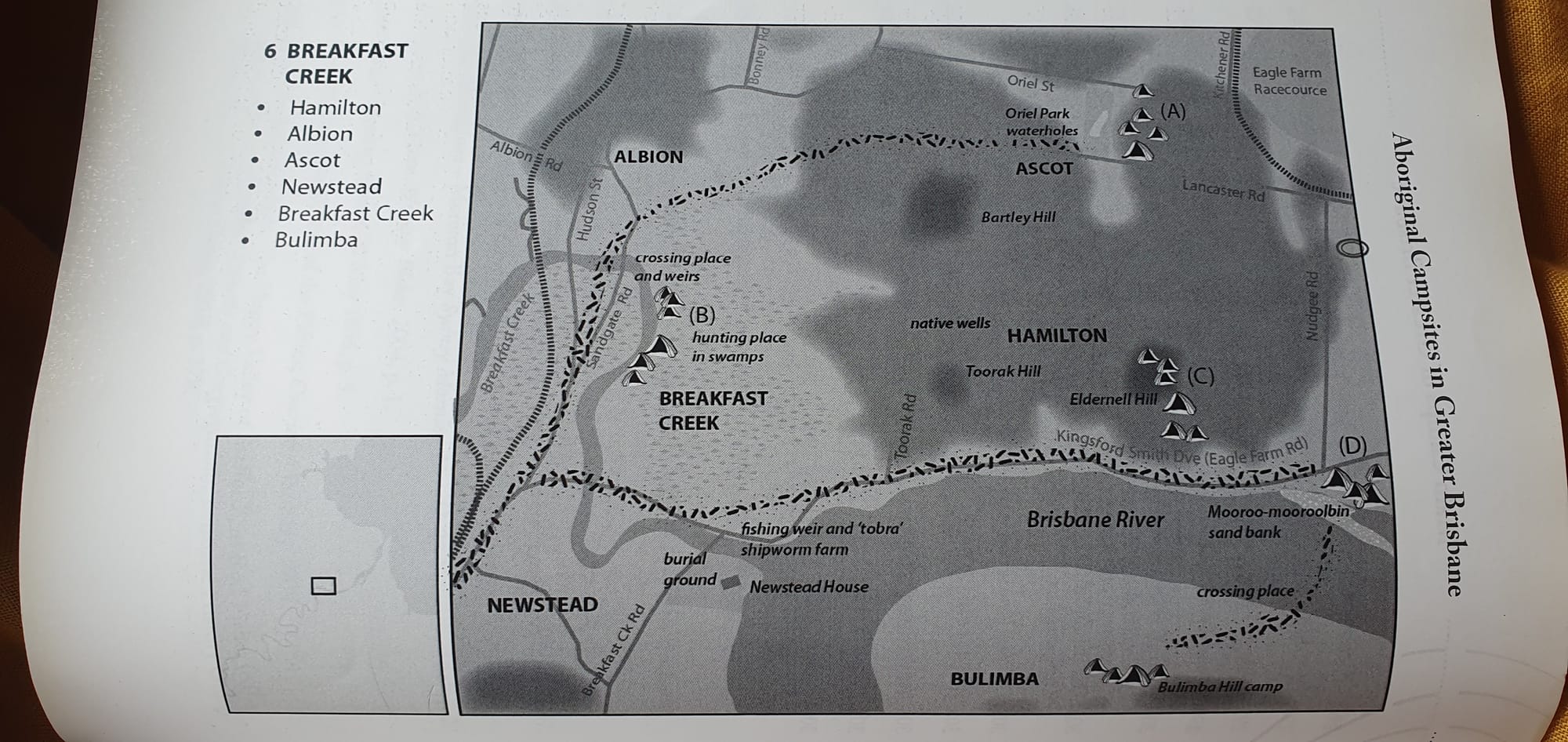

For thousands of years before Europeans showed up, the land around the confluence of Maiwar and Yowogerra hosted multiple Aboriginal villages of varying sizes, which persisted for decades after the Invasion began. The settlements began on the creek’s northern bank, in what’s now southern Albion. They stretched right through to Yerroll (Hamilton), where a sandy beach, Mooroo-Mooroolbin, was a favoured fishing spot for netting mullet, and large sandbars made for an easy crossing over the river to Bulimba.

Most remaining green spaces around this part of the city – including Newstead Park, Crosby Park, the now greatly-reduced Hamilton Park, Oriel Park, Bartley’s Hill, and the greyhound and horseracing tracks at Albion and Eagle Farm – were preserved from the expanding colony’s first waves of development in large part because they were occupied by Aboriginal people, or were regularly used for hunting or ceremonial purposes.

Part of Garranbinbilla (Newstead Point) was likely a sacred burial ground. Botanist Charles Fraser reported in 1828 that he saw “hollow logs filled with the bones of blacks of all sizes” and JD Lang observed in 1845 that trees there “were scored with the tribal or totemic markings of the dead.” The colony’s first Police Magistrate, Captain John Wickham, decided to live there.

In his 2015 book Aboriginal Campsites of Greater Brisbane, historian Dr Ray Kerkhove suggests the Breakfast Creek area was possibly the largest First Nations settlement in the entire lower Brisbane valley. Drawing on Oxley’s journal entries, he highlights how the strong Aboriginal presence was a key factor in the explorer’s initial recommendation that the area might prove suitable for a new British colony.

It’s only after delving into Dr Kerkhove’s excellent research that I realise that even the green oasis of Yowogerra Park, where I’m sitting to write, was itself a village site, or perhaps just downhill from one.

No wonder this place is giving off such strong vibes. Historical records show police raided and trashed the settlement (named in some sources as Ti-Tree Camp) in 1852, 1859, 1861, 1865 and 1867. How many more raids and attacks were not officially reported?

In contrast to other story-laden areas of Brissie like Post Office Square, Musgrave Park and West End’s Boundary Street, I've found comparatively little public First Nations commentary and theorising about Breakfast Creek. It feels wrong to have to rely primarily on non-Indigenous historians and colonial newspapers. So much has been lost or covered up.

Many early colonial commentators described Aboriginal settlements at places like Breakfast Creek as fringe camps – conjuring an image of the occupants as displaced hangers-on who depended upon the growing European town for handouts and casual work. However Dr Kerkhove astutely points out that so-called 'fringe camps' were actually continuations of much longer histories of Aboriginal occupation, and that the creek and surrounding country was a towrie – the main hunting and resource area – of one of the largest clusters of Aboriginal people in the Brisbane region.

The low country around the mouth of Yowogerra/Enoggera/Breakfast Creek was a fertile floodplain – a convergence and transition point between different ecosystems, where a wide variety of foods would have been available year-round. In addition to the fish and other game moving along the waterways, periodic flooding of both the creek and the main river would have deposited fertile soils to nourish many different medicinal and edible plant species.

Tom Petrie (via his daughter Constance, p75) described how in addition to the large, ingenious fish traps and weirs constructed along the waterways, and the rocks that were strategically placed in the shallows to maximise production of easy-to-access oysters, local Aboriginal families stacked casuarina tree logs in the Maiwar and Yowoggera intertidal zones to attract and harvest kanyi, the wood-boring mangrove worms which are an excellent source of protein (having tried them myself up in Arnhem Land, I think they taste better than oysters).

Rather than a hunting ground visited seasonally or cyclically by wandering nomads, the area around Yowoggera Creek hosted permanent Aboriginal settlements. At least some proportion of the community remained in place year-round and allowed the food to come to them, while stewarding and adjusting landscapes to maximise yields without over-exploiting natural resources.

The Breakfast Creek population centres were not parasitic fringe camps. If anything, the Europeans’ small, newly-established colonial outpost was the fringe settlement, heavily reliant upon the knowledge, resources and labour provided by Aboriginal people.

Understanding all this is important in how we think about the birth of our city. Not only did the first European residents of the region directly exploit the land itself; the colonisers also depended on trade or charity from local Aboriginal people, as well as upon their manual labour (both freely given and coerced). Right up to the 1900s, records abound with references to Aboriginal people harvesting and selling foodstuffs like fish and honey to the white settlers, along with a host of other locally-crafted resources. They were also relied upon as ferrymen and boat pilots to navigate the river’s maze of sandbars.

In 1861, The Courier stated (in specific reference to Breakfast Creek) that “Until recently, the inhabitants of Brisbane depended mostly for a supply of fish upon the aborigines [sic] of this locality, very much, no doubt, to the profit, in a pecuniary sense, of these sable sons of the soil.”

Thinking about how limited and inconsistent the supply of meat from livestock could have been in the new colony’s first decades, and how inferior European fishing methods were, it seems plausible that the prosperous Aboriginal fishing town of Breakfast Creek may have served as a major, essential source of protein for Brisbane’s first British settlers.

The Aboriginal settlements of Yowogerra and Yerrol are mentioned frequently in colonial accounts throughout the 1800s, sometimes as a source of essential trade with those who lived in Brisbane Town, and sometimes as a base from which the Aboriginal landowners organised raids and counterattacks against settlers spreading further into their territory.

“As the raids suggest, Breakfast Creek was a significant thorn in the side of colonists. For decades, there were reports of hostilities: raids on gardens, robberies, harassment, and counter-attacks by police and farmers. Alex Bond, a Kabi man, recalls his mother Penny Bond describing the area as a ‘battle front’. Police regularly chased Aboriginal people across the creek each sundown. Tit for tat, camp residents treated settlers who ventured onto their side of the creek as fair game. Aboriginal defiance was the main reason for an 1850 petition from Breakfast Creek colonists demanding police protection. The area remained largely unsettled 32 years after Brisbane was established.”

While early European commentators sometimes spoke reductively of the Aboriginal ‘villages’ of Breakfast Creek, it’s worth noting that until the late 1840s, the Aboriginal population around the creek probably exceeded the population of the main British colony two kilometres to the south.

Although it didn’t look like one to European eyes, the network of settlements beside Breakfast Creek and along the river towards Hamilton was, in essence, an Aboriginal town (albeit slightly more spaced out than most European towns), complete with its highways and trading posts, industrial hubs, burial sites and sacred places, artistic centres, sports grounds, designated short-term accommodation areas for visiting clans, and several hundred permanent residents.

The frontier town we’ve forgotten

Between the 1830s and 1870s, the creek itself became a territorial boundary between the British colony and the heavily populated Aboriginal town. To keep the invaders at bay, the locals engaged in strategic sabotage and targeted raiding of food stores, particularly when settlers tried to claim land to the north and east of Yowoggera.

But that first shot fired by Lieutenant Butler beside the creek in 1824 had set the tone for the rest of the century.

White invaders launched repeated attacks of varying intensity upon the Aboriginal town of Breakfast Creek. Some of these attacks were state-sanctioned police forays, while others were led by vigilantes. A well-documented attack from 1859 – described by the Moreton Bay Courier as a ‘Wanton Outrage’ – involved a squad of well-armed police crossing the creek and moving from settlement to settlement, shooting indiscriminately and setting fire to as many as eighty Aboriginal homes.

It’s striking how tenacious local First Nations people were about returning, rebuilding and doggedly clinging on to this bend of the river. Every few years, British invaders would chase them away or set fire to their homes, sometimes murdering those who were too slow to flee. Yet the Breakfast Creek clans kept coming back, persisting in the face of relentless violent attempts at dispersal, still hunting, foraging, passing on knowledge, and conducting ceremony on the very doorstep of Brisbane.

It wasn’t until the 1880s that Europeans began settling to the north of Breakfast Creek in larger numbers, and of course Aboriginal people remained in the area even after that.

This brief, patchy glimpse of Yowoggera Creek’s history highlights how wilfully negligent our city has been at remembering and reflecting upon our recent past (and what it might mean for us in the present and future). Despite easily-accessed historical records, and generations of local historians and artists continually finding new ways to share these stories with the wider population, only a tiny percentage of Brisbanites would be familiar with them.

There are few – if any – historical plaques and signs in public places around Newstead, Ascot and Albion that describe the large Aboriginal settlements of the area and the long-running campaign to disperse them. Breakfast Creek Hotel has a 1500-word ‘History’ section on its website, but makes no mention of Aboriginal people or the area’s tumultuous past. Street names are all of European origin, as are all the suburb names on both sides of the creek (it’s hard to get past the irony of ‘Albion’ – an ancient name for the British Isles – being imposed upon one of the Maiwar River’s largest and most persistent Aboriginal towns).

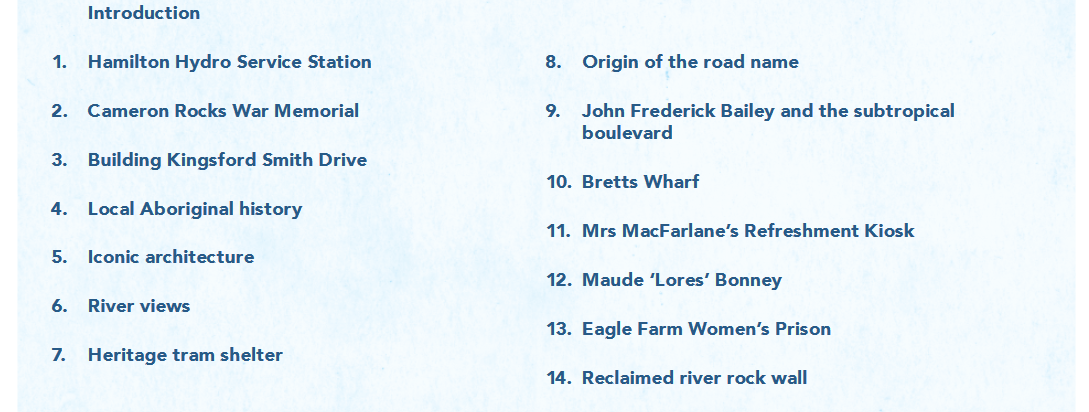

In 2019, Brisbane City Council published a heritage trail booklet called “Roam the River from creek to wharf: Breakfast Creek to Bretts Wharf.” The 21-page walking guide features a range of historic landmarks, several of which have long since disappeared, including a relatively unremarkable petrol station that operated for 65 years until its closure in 1996, and a once-popular refreshment kiosk that opened sometime in the 1890s and closed in 1921.

The guide dedicates only a single cursory page – 8 sentences – to ‘Local Aboriginal History,’ making no mention of the complex fish traps, the burial trees, or the thousands of years of thriving trade and cultural exchange with clans that visited regularly from Moreton Bay’s islands and further afield. Unsurprisingly, there’s no reference to the repeated violent attacks on the Breakfast Creek Aboriginal settlements in the years immediately preceding the opening of ‘Mrs MacFarlane’s Refreshment Kiosk’ (the guide offers 12 sentences on the topic of the kiosk).

In a 21st century context, these kinds of superficial, tokenistic references to the long history of First Nations occupation are in some respects just as damaging as the many documents that obliterate First Nations people from the story altogether. Condensing tens of thousands of years of history into the same number of paragraphs afforded to far briefer, less significant events muddies our sense of proportion and context, as if to say, “Oh yes of course Aboriginal people were here for tens of thousands of years, but nothing they did or thought about was important enough to warrant a mention.”

It would be better to face the uncomfortable truth: that thousands of significant deeds and events shaped the Maiwar Valley (and thus our city) prior to the European invasion, but a sustained campaign of colonial violence and racist oppression over the past two centuries has destroyed much of that knowledge.

In recent years, Breakfast Creek has featured in local government political statements connected to the new $67 million bicycle and pedestrian bridge that Brisbane City Council built across the creek mouth. None of this commentary mentioned the creek’s past as a frontier of conflict between European invaders and local Aboriginal clans. It’s simply the location of the new ‘critical bikeway link’ – a “key piece of Olympic and Paralympic infrastructure” connecting to the proposed Athletes Village at Hamilton.

Selective obliterations of the city’s Aboriginal past are of course foundational to the colonial project. Commonly identified landmarks of this part of Brisbane include Newstead House – Captain Wickham’s colonial residence built in 1846 (“Brisbane’s oldest surviving residence”), and Breakfast Creek Hotel, built in 1889. The unconscious (or conscious?) emphasis on buildings dating back to the area’s early European history entrenches the erasure of Aboriginal presence, again implying that there was nothing before this time worthy of remembrance.

In this sense, while Breakfast Creek lingers as the redundant name of a waterway that already has another name, the Aboriginal town of Breakfast Creek – which featured so prominently in the invaders’ minds and public discourse throughout the 1800s – has ceased to exist in our city’s mainstream memory.

How many other such places across so-called Brisbane are subject to this pattern of forgetting and rewriting? And how does this limit our conversations about what kinds of futures might be possible?

“They stole our ground where we used to get food, and when we got hungry and took a bit of flour or killed a bullock to eat, they shot us or poisoned us. All they give us now for our land is a blanket once a year.”

– Dalaipi in 'Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences'

Erase marginalised histories, obliterate alternative futures

First Nations writers such as Chelsea Watego have long highlighted the harms of erasing and delegitimising urban Indigenous identities through racist discourse about so-called ‘real’ Aboriginal people, who supposedly only live ‘out west’ or ‘up north.’ Overlooking the historical existence of Aboriginal towns like Breakfast Creek, and how integral they were to the establishment of colonial cities like Brisbane, reinforces this.

In his excellent Frontier Wars series, Gamilaraay and Kooma podcaster Boe Spearim and his guests repeatedly allude to the way that contemporary progressive truth-telling about the colonial invasion often focuses on the many stories of violence and dispossession that took place in ‘the bush’ or in regional towns, de-emphasising capital cities like Brisbane.

Non-Indigenous Australia is slowly moving beyond decades of outright denial about the Frontier Wars. A colonial frontier is now finally crystallising in our collective memory. But we’re still inadvertently relocating it further away from the metropolis. Even in the South-East Queensland context, many more of us have probably heard about the flour poisoning massacre at Kilcoy station than about the repeated attacks on the Aboriginal town/villages at Breakfast Creek.

This serves to exceptionalise cities – particularly Australia’s east coast capitals. It’s almost as though they materialised abruptly in a ‘post-conflict’ landscape sometime after the invasion had ‘finished’, excluding them from practical conversations about returning or paying reparations for stolen land. If we erase First Nations people’s persistent presence – not just individual households and families, but entire villages and towns – within what is now the urban footprint, we also narrow our capacity to imagine what decolonisation and justice could mean in urban areas.

“The Yagera people and the Turrbal people deserve a homeland, even though they live in the city.”

– Uncle Coco Wharton, 'Let's Talk' Murri Radio, 2 July 2024.

Even in ‘progressive’ non-Indigenous circles, conversations about land rights and giving back stolen land continue to focus on locations beyond the city limits.

During my recent mayoral campaign, one of the most interesting elements of our proposal to compulsorily acquire and redevelop Eagle Farm racecourse for public housing and parkland was the suggestion that ownership of the land itself should transition to a non-profit Aboriginal organisation, rather than direct government ownership – a model that would give First Nations people long-term control over this 40-hectare site. But this idea wasn’t taken very seriously by Greens leadership, and campaigning focussed more on creating public housing and community facilities, not returning stolen land. The Aboriginal town that had extended from Breakfast Creek out to Eagle Farm – probably for thousands of years – didn’t exist in the minds of the average Greens supporter, which narrowed the parameters of debate and made it much harder to imagine creating a new Aboriginal-owned, multicultural community on that site.

Developer picnic or land back?

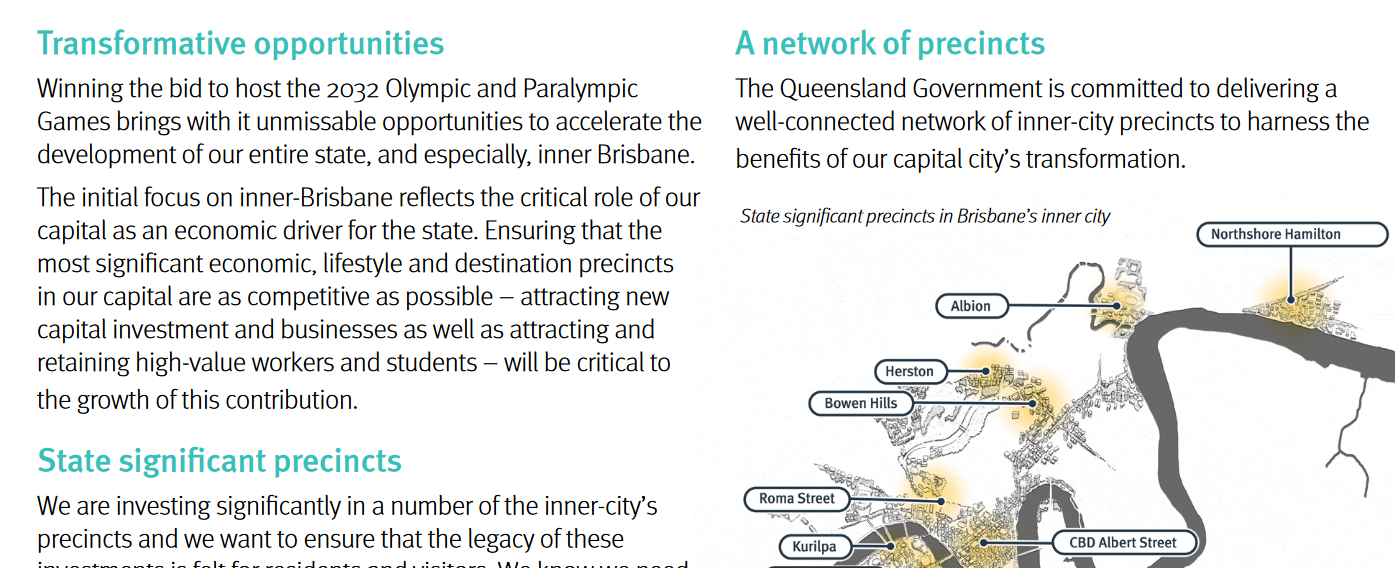

In May 2024, the Queensland Government confirmed that the southern half of Albion – a key precinct of the Breakfast Creek Aboriginal town, and currently full of industrial workshops and warehouses – was on its list of ‘state significant’ inner-city areas where the government hopes to create a “mixed-use lifestyle and destination precinct.”

This echoed proposals in the city council’s Brisbane’s Inner-City Strategy document (launched at a Property Council breakfast in April 2023) to rezone southern Albion for high-density highrise development, despite it being one of the most flood-prone parts of the entire metropolis.

The site where South-East Queensland’s Frontier War began is staring down another frenzy of real estate speculation.

Some of the blocks being considered for redevelopment are barely 1.5m above AHD sea level (half a metre above peak high tides) and flooded severely in February 2022. Former Aboriginal residents kept their huts on higher ground during wet seasons, and used the lower-lying lagoons and wetlands as food sources. But capitalist developers are eager to build over all of it, pocket the profits and leave future residents to deal with the consequences.

Rezoning flood-prone industrial sites for highrise development represents a huge transfer of wealth to whichever non-Indigenous property speculators own the blocks at the time of rezoning. A warehouse that might currently sell for $2 million or $3 million could suddenly be worth $30 million.

If the rezoning is confirmed and developers begin selling units off the plan, returning land ownership to non-profit Aboriginal-controlled entities would become even more complex and expensive.

But there’s another pathway available to us as a city.

Instead of a private developer free-for-all around the mouth of Yowoggera Creek, the city could acquire sites while they’re comparatively cheap, before any rezoning occurs, then explore options to hand them back, not to Indigenous individuals, but to non-profit, democratically-run First Nations collectives. Some blocks on higher ground could be developed as medium-density housing (prioritising Aboriginal families), with ground-level community facilities and art spaces, while most of the precinct is restored as green space, similar to the bountiful hunting grounds that fed Yowoggera residents for thousands of years before the invasion.

Not only would this approach improve the area’s flood resilience and avoid exposing future residents to sea level rise impacts – it would represent a significant, tangible step towards rectifying past wrongs and meaningfully recognising First Nations sovereignty.

For thousands of years, a large Aboriginal town prospered around Breakfast Creek, the swamps of Albion, the slopes of Ascot and the Hamilton riverbank.

It persisted for almost a century after the first European invaders reached Moreton Bay, and every settler in the emerging Brisbane colony knew about it. But acknowledging its significance as an initial landing point of the invasion was politically subversive and inconvenient.

The Aboriginal town was obliterated, both physically and from the stories the city tells about itself, to such an extent that now, returning urban land to First Nations ownership is dismissed as far-fetched or impractical, while profit-driven proposals to build highrises on floodprone swamps are treated as foregone conclusions.

So how will we remember Breakfast Creek 200 years from now?

Note: In writing this article, I'm conscious of my subject position as a non-Indigenous settler, and of the under-representation of First Nations voices and perspectives in this piece. I acknowledge and offer my respects to the elders and rightful owners of this region, and apologise whole-heartedly for anything important I've overlooked or omitted.

If any Aboriginal readers with connections to Yowoggera/Breakfast Creek read this and have thoughts that you'd like included, please email me at office@jonathansri.com and I'll happily incorporate updates or publish a follow-up article.

If you value writing like this and would like to support me to publish more often, please consider signing up for a paid subscription...

Member discussion