Queensland's boarding house trap: Why some people 'prefer' a tent in the park

When an unhoused person is forcibly moved on from camping in a public park or square, government officials will sometimes claim they were 'offered housing' and 'turned it down.' But allegations that a rough sleeper 'refused housing' don't usually relate to genuinely affordable public housing. In fact, often the person was merely offered a vacancy in dangerous, unhealthy, for-profit rooming accommodation.

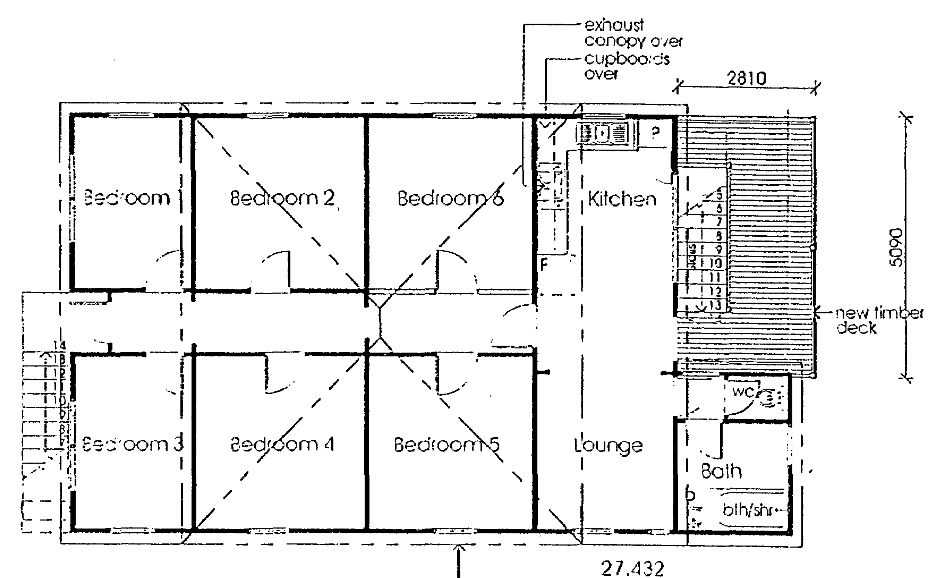

Rooming accommodation comes in many forms of varying quality. But people coming off the street can usually only get into the oldest, most crowded boarding houses. You get a hot, cramped, dimly-lit bedroom – sometimes as small as 8m2 – sharing kitchenettes, bathrooms and maybe a smoking courtyard with ten other people.

Boarding houses are often gender-segregated, and the cheaper rooms are only big enough for single beds anyway, so homeless couples have to split up in order to move into this kind of housing. While more weatherproof than a tent, these accommodation options are still hot and stuffy, cold and drafty, and/or heavily impacted by cockroach, rat and mould infestations.

Whereas in a standard rental, you might at least have the stability of a 6-month or 12-month lease, rooming accommodation tenants can be evicted with only a few weeks’ notice, or even less if they break one of the landlord’s arbitrary rules (it doesn’t matter what the relevant legislation technically says – most of these tenants lack the knowledge or resources to assert their rights).

Tenants of boarding houses and backpacker lodges (the kind that cater to low-income locals, not international travellers) sometimes complain about theft of food and other possessions, widespread drug abuse, and violence. For people transitioning out of homelessness who also have mental health or drug addiction challenges, these environments can be particularly toxic.

The kicker is that these days, the rent in these places is still unsustainably high for someone who’s looking for work. A cramped boarding house room with minimal ventilation or views can still cost $150 to $250/week. The slumlord owners know how desperate their tenants are.

Clients transitioning off the street often don’t have good rental histories, positive references from past landlords, or proof of stable income. In a system that allows landlords and real estate agents to discriminate based on class and race, this is the only kind of private sector housing they have any hope of securing, but it can become a trap for vulnerable people. The poor conditions and the high living costs mean tenants often get stuck in a rut, unable to afford to relocate to better housing, while both their health and self-help capacity deteriorate further.

Perversely, Queensland's Department of Housing and Public Works treats people in accommodation situations like this as 'housed,' so if you do agree to move into a boarding house, you're immediately removed from the high-priority waiting list for public housing. You could end up living like this for a long, long time.

The churn

Imagine you've been sleeping on the street for a couple months after losing your job. You've been robbed twice and your health isn't great, but so far you haven't been able to afford the meds the doctor prescribed. You finally get on Centrelink and move into a boarding house (recommended by a local charity). Paying bond takes all your meagre savings, but at least you're out of the rain.

The dodgy-reno building is old but not at all charming, with peeling paint, exposed asbestos and a weird smell constantly wafting up from the drains. The hallway light doesn't work and the bathroom floor is always wet cos the shower seals have rotten through. The bedroom walls are thin.

Most of your neighbours are friendly enough, and easy to live with. But one has serious mental health issues and wakes you with his screaming at least once a week. Another has an alcohol addiction and hangs out drinking on the grotty couch beside the front door all afternoon, pestering you to join his non-stop binge sessions (not ideal when you're trying to stay sober).

The guy in room one is dealing drugs – he meets half a dozen strangers a day beside the back steps, sometimes getting into late-night noisy arguments with customers or suppliers. No-one stops him cos he bribes the property manager.

Someone keeps taking your food from the kitchen but you can't work out who – you don't even know everyone's names. Because the kitchen isn't secure, most tenants keep food in their rooms, which perhaps explains the ubiquitous cockroaches and mouse poo.

The landlord has installed cameras in the kitchen and hallway that spy on everyone 24/7 – you know he'd kick you out in a heartbeat if you broke his rule against bringing guests around, but there's not really any space to have a mate over for a cuppa anyways.

The rusty, coin-operated washing machines under the house cost $3 a wash and sometimes stain your clothes. You often spend more money rewashing them at the laundromat. If you accidentally lock yourself out of your room while making toast or cleaning your teeth, the corrupt property manager charges you sixty bucks just to let you back in.

Your room lacks a ceiling fan, and only has one small, west-facing window (which jams frequently) with no mosquito screen. If you close the curtains to keep out the sun and the mozzies, it gets stuffy very quickly. Between your neighbour's noisy nightmares, the fights under the back steps, and how hot the room is, you rarely get a good night's sleep, and afternoon naps are impossible.

Over half your Centrelink pay goes towards rent, so even when you grab a few free meals from local charities, you're not saving anything, and you're too depressed and sleep-deprived to put much effort into looking for work. Your room is slowly destroying your physical and mental health, and you actually feel lonelier than you did when you slept rough alongside mates under the bridge.

When a serious fight breaks out in the hallway over someone playing loud music, or taking too long in the bathroom, or leaving a mess in the kitchen, and two neighbours with serious anger management issues start shouting death threats, you can't help wondering if you're better off with a tent in the park after all...

I'm currently working on a longer piece about how we should collectively respond to the persecution of unhoused people in Brisbane. To support this writing and receive a monthly round-up of the latest articles I've published, please sign up for a paid subscription if you can...

Addendum: After further reflection, and taking note of responses from readers, I want to emphasise (just in case it's not obvious to some) that not everyone sleeping rough or living in boarding houses has trouble with substance abuse, and not all rooming accommodation is as bad as the kinds of housing described above.

The point of this article is to highlight just how bad certain boarding houses are, and help readers understand why some people in crisis might reasonably prefer to continue sleeping rough and wait for public housing. There's so much more to say about rooming accommodation – several commenters on social media have rightly highlighted a growing pattern of landlords deliberately exploiting disabled people, something I hope to explore in future articles.

When writing about the housing crisis, we should be really cautious about reinforcing harmful stereotypes, and remember that not everyone is going to take away the same messages from articles like this one. A piece this short necessarily only paints a narrow, simplified picture. But I'm hoping most readers are wise enough to appreciate just how complex and diverse the experiences and circumstances of people experiencing housing precarity actually are.

Member discussion