7 years as a local politician turned me off ‘big government’ – but there are other alternatives to neoliberal capitalism

I think it happened without most of us noticing.

Decades of neoliberal privatisation and public service cuts put the Australian left on the back foot.

As the Labor party lurched further to the right, various progressive NGOs, unionists and election-focussed Greens supporters found ourselves fighting rearguard actions against public service cuts, continually arguing for government ownership of key infrastructure and facilities and a greater role for the nation-state in ensuring no-one slips through capitalism's cracks.

In the course of such struggles, our political imaginations have narrowed more than we realised, and we’ve forgotten something important:

There are big, crucial differences between:

a) decentralised networks of non-profit, localised, community-controlled services and facilities

and

b) ‘public’ services that are centrally controlled and administered by large, hierarchical government entities.

When I was first elected as a city councillor, my politics were – if I’m honest – a little conflicted.

On the one hand, I was immersed in counter-cultural music and arts communities, where cynicism of big, bureaucratic, over-regulating governments runs strong, and people are more invested in autonomous community-led projects. These are the kinds of people who would rather, for example, set up several smaller communal farms and food co-ops than argue for a single, large, government-owned supermarket enterprise that directly competes with Coles/Woolworths.

But I was also connected to, and influenced by, plenty of statist (for want of a better term) social democrats. They believed governments which properly taxed the 'big end of town' and redistributed that wealth to fund public infrastructure and services could deliver everyone a better quality of life while protecting the environment from profit-driven degradation.

This worldview held that widespread scepticism of government services arose primarily because private sector outsourcing and insufficient public funding had left them crappy and unreliable. Yes, a lot of public housing stock was poorly maintained. And yes, the trains were unreliable. But that wasn’t because public transport and public housing were inherently flawed concepts – they just weren’t getting sufficient funding and support from politicians who’d been brainwashed by free market dogma. People had only lost faith in government because neoliberal governments had been so shitty for such a long time!

I was persuaded by this narrative for a while. But during my 7 years as an elected representative, observing and working with local council officers, but also state and federal public servants, I realised there was more to it. Over time, my opinion changed.

Centralised, top-down governance is inherently inefficient

Leftwing critiques of neoliberalism are still largely correct. Yes, part of the problem with our government (at all levels) is that major party politicians maintain legal and regulatory frameworks that privilege big corporations, while stripping public services of support until they become so useless that few of us even complain when they’re sold off cheaply to the private sector.

But beyond that, large entities that are centrally administered from the top down – whether they’re government departments, bigger regional councils, NGOs or privately owned, profit-driven corporations – are by nature bureaucratic and detached from on-ground realities. They tend to be impersonal, undemocratic and inefficient (i.e. slow and resource-intensive) even when they’re not controlled by free market ideologues who’re trying to privatise and outsource everything (at this page you can find three case studies from my time as a city councillor which help illustrate why I've reached this conclusion).

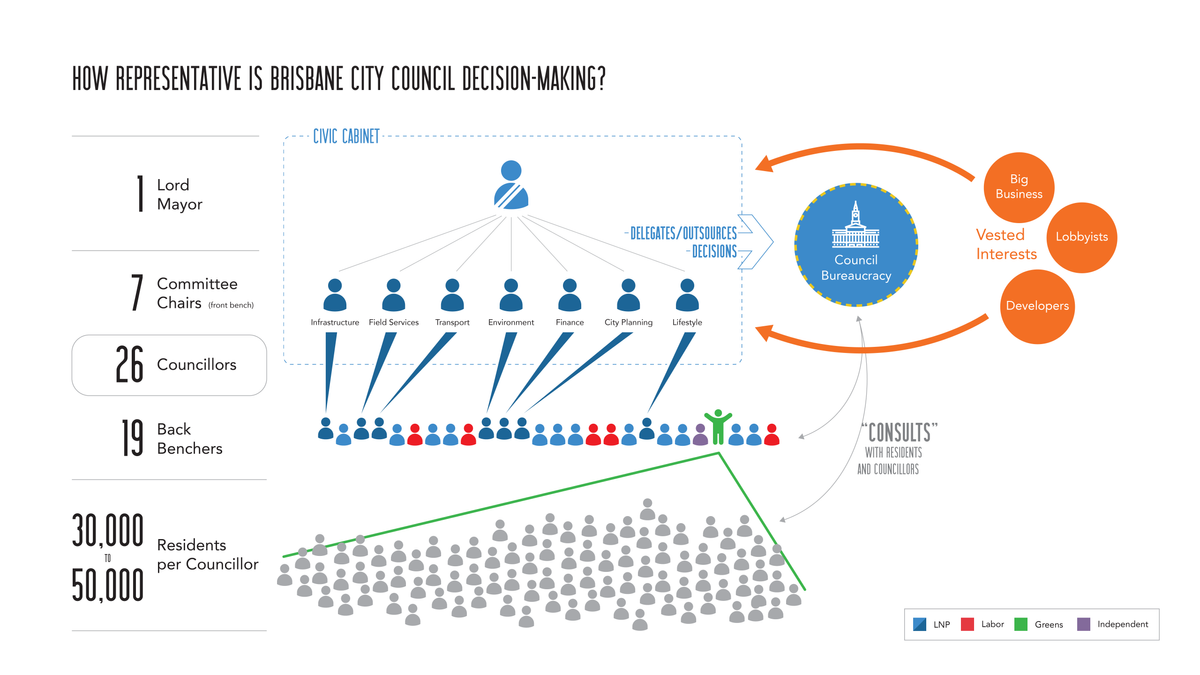

Cost-intensive bureaucracy and anti-democratic disconnection from community become more pronounced at higher levels of government. Some public servants know this intuitively. This is why, for example, so much state and federal funding for road infrastructure is simply passed on to local governments via grants for specific projects – the council does it cheaper. Queensland Health even contracts Brisbane City Council to deliver free immunisation clinics. But large city councils like BCC are themselves top-heavy, over-centralised bureaucracies, and their lack of legal autonomy from higher levels of government (or their cultural reluctance to fight for greater autonomy) often reduces them to acting as organs of the nation-state.

"The Right, at least, has a critique of bureaucracy. It’s not a very good one. But at least it exists."

- David Graeber, 'The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy' (p6)

The bigger the entity, the more time and money seems to get chewed up by managerialism, overplanning, and paranoid levels of risk mitigation. For senior departmental decision-makers to even keep abreast of how other government departments might be impacting their spheres of influence, they would have to spend hours a day just reading and producing briefing papers and attending cross-departmental meetings.

If you’re making policy and planning decisions about a neighbourhood or workplace, but you’re not embedded in that space and maintaining meaningful relationships with the actual people who exist there, it takes lots of extra work and resources to ensure you’re not overlooking or oversimplifying what’s really going on.

“Officials of the modern state are, of necessity, at least one step— and often several steps— removed from the society they are charged with governing. They assess the life of their society by a series of typifications that are always some distance from the full reality these abstractions are meant to capture. Thus the foresters’ charts and tables, despite their synoptic power to distill many individual facts into a larger pattern, do not quite capture (nor are they meant to) the real forest in its full diversity. Thus the cadastral survey and the title deed are a rough, often misleading representation of actual, existing rights to land use and disposal. The functionary of any large organization “sees” the human activity that is of interest to him largely through the simplified approximations of documents and statistics...”

- James Scott, 'Seeing Like a State' (page 76)

Consistently during my years as a city councillor, I observed that the best decisions and solutions came from public servants who were intimately connected to the neighbourhoods and workplaces they were exercising power over.

The landscape architects who lived in West End had better ideas of what park design approaches would suit 4101’s particular culture of public space use. The traffic engineer who cycled to work was more competent at understanding and rectifying residents’ bike lane safety concerns than other engineers who drove everywhere. The grants administrator who also moonlighted as a musician and regularly attended weekend festivals had better judgement than their colleagues about which creative project proposals would make best use of council funding.

None of this should surprise us. Assuming they haven't been denied access to crucial information or brainwashed by consumerist propaganda, people are – generally speaking – experts in their own lives, and often have good ideas about how to make their communities and workplaces better. But hierarchical, centralised governance norms and structures actively cut public servants off from communities, putting more distance between their work responsibilities and personal experiences.

The overarching point here is that I think the Greens – and other lefties – might be mistaken to insist that centrally-controlled, government-led services and projects are the best answer to the big challenges and gaps our society is grappling with. Such approaches are inflexibly one-size-fits-all, and structurally resistant to meaningful democratic responsiveness and accountability.

I've written previously about some of the participatory democracy trials I conducted as a city councillor.

While they showed that many residents were eager to have more say over the council decisions that affected their lives, we also found it very difficult in practice to democratise decision-making over public sector processes that were designed to be centrally controlled and administered from the top down.

As experiences from jurisdictions like Byron Shire Council and the Australian Capital Territory suggest, even when Greens elected reps do win substantial control over government bureaucracies, these anti-democratic structural features persist (and Greens elected reps sometimes get blamed for them) unless they are actively dismantled.

In fact, it's hard to find examples anywhere in the world where major statist, government-run projects and programs aren't legitimately criticised for wasting money, or for overlooking and oversimplifying a community's needs (which are inevitably more diverse and complex on the ground than a census or 'consultation report' might suggest).

Even one of the most well-known social democracy success stories, Vienna's rightly-lauded social housing system, is administered at the city level rather than by Austria's national government, and was established as part of a much broader municipal socialist program influenced by strong localist and communitarian (as opposed to state socialist) tendencies. And today, roughly half the city's subsidised homes are actually owned/managed by smaller housing cooperatives ('Genossenschaftswohnung') rather than by the City of Vienna itself. In recent decades, for various reasons, the city has relied predominantly on entities like the Genossenschaftswohnung co-ops to build new subsidised housing, rather than directly building public housing. On closer inspection, the 'Vienna model' looks much more localised and bottom-up than Australian Greens proposals for a federal public property developer.

Governments kinda just suck

I don't for a second buy the rightwing rubbish that 'free' markets full of unregulated profit-driven entities competing with each other will tend to manage and distribute resources efficiently, or meet people's needs equitably. But centralised governments are also lumbering, clumsy behemoths. True sustainability and collective resilience comes not from concentrating power in the hands of a small number of elites, but from spreading it around.

The public cynicism I've observed towards Greens' suggestions that a government entity could directly (and cost-effectively) build tens of thousands of homes per year isn't entirely due to neoliberal propaganda. Even a lot of public servants who understand how governments work in practice seem sceptical of such visions.

The point of this article is not to argue that the Greens should shift away from statist policy solutions because they're politically unpopular, but because nation-states are oppressive, dehumanising entities that we should seek to render redundant rather than empower further.

Unfortunately, many on the Australian left pay only passing attention to First Nations critiques of the colonial nation-state. The deep violence that nation-states inflict upon First Nations people is beyond the topic of this article, but for further reading on this, I recommend starting with papers like First Nations and the Colonial Project by Professor Irene Watson and books such as Another Day in the Colony by Chelsea Watego, and The White Possessive: Property, Power and Indigenous Sovereignty by Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson (older works by non-Indigenous authors like Pierre Clastres's Society against the State are also worth a look, though they have their flaws and limitations).

Looking around the modern world and back across history, we have no strong evidence to contradict the supposition that even the most 'progressive,' anti-racist version of centralised, hierarchical governance that we might imagine would likely still deliver outcomes which oppress or marginalise First Nations communities, no matter how well-intentioned the politicians at the top of the pyramid might be.

Ever since nation-states began emerging four or five hundred years ago (a mere blip in human history), wiser minds than mine have filled entire volumes enunciating the harms they inevitably cause. The services modern nations offer are conditional upon citizens ceding substantial autonomy and privacy, and the concentration of significant power and resources under government control invariably creates fertile ground for corruption and abuse.

So isn't it at least possible that statist proposals like government-run public housing construction projects and massive state-owned solar power plants might not be the best imaginable way forward?

Alternative models are everywhere

Here's the good news: We need not content ourselves with a binary choice between capitalist dystopias (where profit-driven corporations enclose the commons while ripping off workers and customers), or resource-intensive government bureaucracies (implementing rigid, one-size-fits-all systems that fragment communities into atomized service-recipients). Numerous contemporary examples here in Australia, and across the world, demonstrate that this is a false dichotomy, and that many other paths are available to us.

What I'm proposing is a much greater emphasis on decentralised, non-profit community-controlled services and facilities rather than those which are directly controlled top-down by the nation-state.

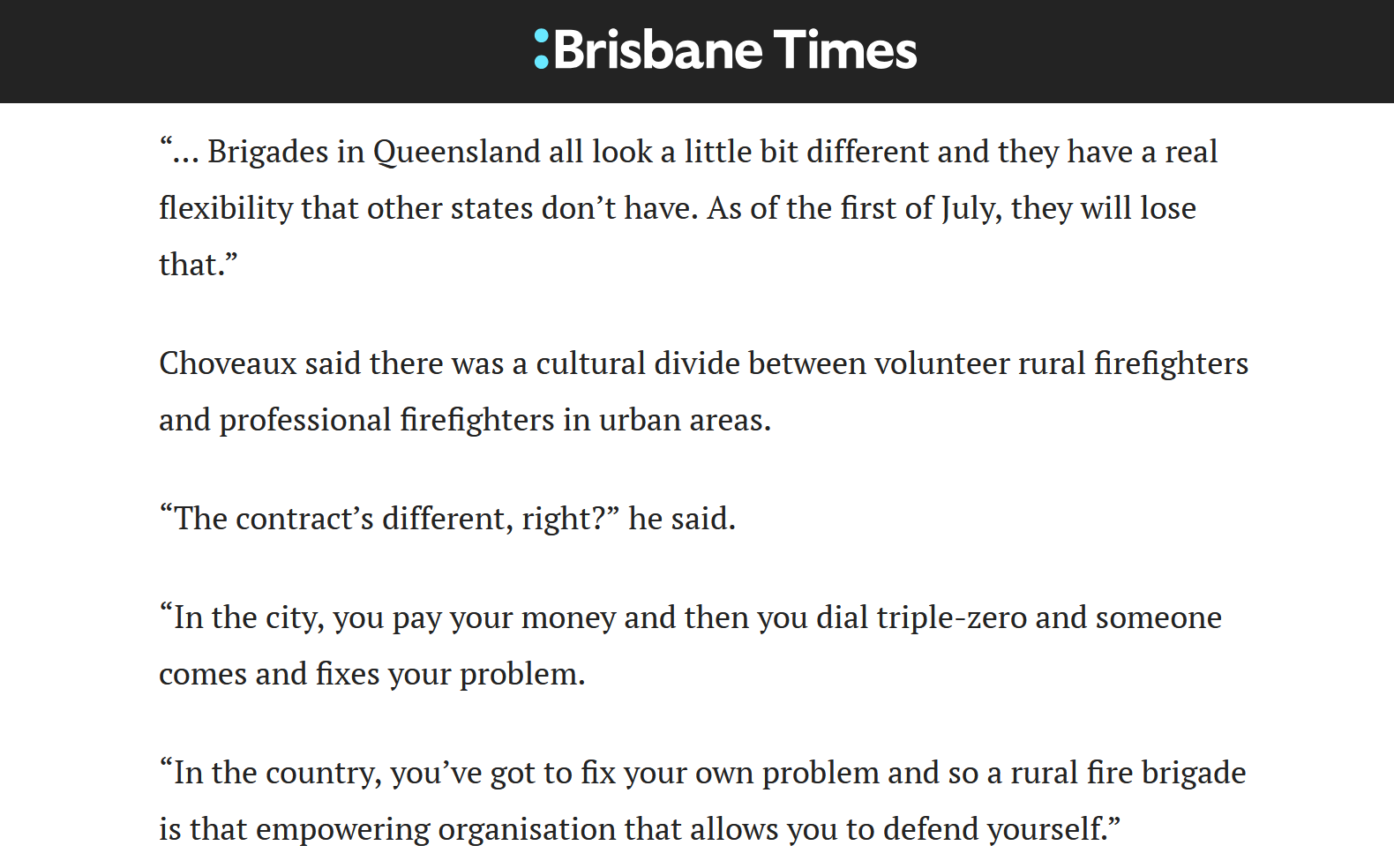

Think, for example, of major community institutions like Surf Life Saving and Rural Fire Brigades. Both of these services receive some government funding and support, but are much more autonomous and adaptable to local contexts than a government department could ever hope to be. Hundreds of life saving clubs are individually incorporated, but are still connected through federated state and national structures. Similarly, individual rural fire brigades have (until recently) had significant latitude and flexibility regarding how they serve their local areas – many aren't incorporated associations at all.

In other contexts, governing authorities have to spend a lot of money either employing public servants, or contracting out to private companies, to deliver essential services like firefighting and open-water rescues. It's an interesting quirk of history that a lot of rural firefighting work is still handled by part-time volunteers, whereas urban firefighting in Australia is completely professionalised.

Surf Life Saving Australia estimates that nationwide, its clubs deliver 16 million hours of volunteer work every year. Even if you assume some of that volunteer work is unnecessary, there's no way that even the leanest and most efficient government department or private company could deliver that kind of service coverage across hundreds of beaches for less than $1 billion per year (it would likely cost our government much, much more).

The decentralised, highly autonomous nature of federated networks like these is illegible, confusing and in some ways even threatening to governments. Consider, for example, the last few years of debates about the unclear legal status of individual rural fire brigades in Queensland and the ensuing, highly-controversial Labor government attempts to bring these brigades and their assets under more direct state control (a move which may well backfire in the long run).

Many rural fire brigade members are rightly concerned that increasing state involvement will lead to more bureaucracy and less local flexibility – a great way to discourage volunteering.

I should note, of course, that neither of these organisations are perfect, and have both – in various ways – played a problematic role in expanding and defending the Australian settler-colonial project. Consider both the increasing surveillance of beaches and coastlines (and associated normalisation of patriarchal white Australian beach culture) and the anti-ecological, colonial approaches to land management that rural fire brigades often recommend and engage in. Professor Moreton-Robinson's chapter 'Bodies that Matter on the Beach' in The White Possessive is well worth a look regarding the origins and function of surf lifesaving.

To be clear, I'm also not arguing that every public service should be delivered by lower-skilled, part-time volunteers instead of properly-paid full-time specialists. But while many statist lefties are reluctant to admit it, there's some truth to the old anarchist critique that when governments insist on stepping in to provide a particular service, this can override pre-existing, collectivised, local systems for meeting people's needs that weren't readily visible to the nation-state, thus undermining community capacity and resilience.

Nevertheless, there are so many more examples of long-running community-controlled services and facilities (some volunteer-based, others revolving around paid employees), from P&C-run school tuckshops to Meals on Wheels to landcare groups, community gardens, kindergartens, bulk-buying organic food co-ops, repair cafes and tool libraries... I could go on for days. When you zoom out further, you also find examples around Australia of local councils owning or helping operate solar power plants, regional airports, contract worker hostel accommodation, farmers markets and grocery stores. I would much rather see these kinds of essential projects and services controlled by local councils than by either the profit-driven private sector or higher levels of government (noting that the degree of democratic influence residents have over their councils varies greatly; I would argue it tends to decrease with larger councils).

Unfortunately, 'community-controlled' is an ambiguous term, and there are many ostensibly non-profit 'community' organisations – especially larger charities and NGOs – that give community services a bad name. There's an important distinction to be drawn between projects that are under genuine democratic control of the people who actually use the services, and impersonal, hierarchical NGOs that operate more like appendages of the government.

But when services and facilities are locally-controlled, communities have greater trust in them, which makes them more effective, particularly in times of crisis.

For example, First Nations journalist and researcher Amy McQuire has highlighted how in 2020, decentralised, Aboriginal community-controlled health services were faster and more effective than their state-run counterparts at responding to covid-19 and implementing public education and targeted health measures without significant backlash from the communities themselves. Many remote Aboriginal communities even proactively introduced their own travel restrictions – in a way that brought residents along with that difficult decision – before the government itself introduced lockdowns (which were far more contentious because they were imposed from the top-down rather than by consent from the bottom up).

Ok so what should the Greens be doing then? Why even run for elections at all?

Our long-term goal should be to render nation-states redundant by gradually building up decentralised, non-profit community institutions and projects, while also promoting cultural norms of people helping each other directly, without the intermediary of non-profit orgs. Having elected representatives (and public servants) in government who back this approach is extremely valuable, even if they're ultimately trying to make themselves redundant.

Greens elected reps could champion the flourishing of decentralised, communal responses (as opposed to unregulated, competitive individualism) via steps like:

- shortening the standard (paid) work week so that people have more time for community-building and unpaid domestic labour/care work

- offering/auspicing free public liability insurance to a wide range of community projects, so they can operate more sustainably within our current, bureaucratic system

- providing free or heavily-subsidised physical spaces for community projects, and putting different groups in direct contact with each other

- insisting that any outsourcing of government responsibilities should be to smaller, local, non-profit entities that are under democratic community control (and not to private businesses)

- tweaking regulations that unreasonably constrain democratic non-profit initiatives, so the regs only apply to entities that have a profit motive to cut corners and cause harm (while it sounds similar, this is a very different political project from neoliberal calls for wholesale deregulation, which tend to empower large, profit-driven corporations, who are themselves highly bureaucratic)

That's just off the top of my head. The Greens sometimes argue for some of these things, but the overall orientation towards the state, and the choices the party makes between advocating statist solutions or community-led solutions, sometimes feel arbitrary and inconsistent. I'm thinking, in particular, of how the Greens focus on calling for greater state funding of institutional childcare and aged care, rather than for a more fundamental restructuring of work schedules and social relationships to enable and empower grassroots, communal networks of care... I don't really want the government to pay someone I hardly know to look after my (hypothetical) kid or my ageing parents; I'd rather a world where me, my partner, my neighbours and my extended family members have ample time and capacity to share this work among ourselves without being paid for it.

In addition to a more holistic, ecological lens, and the insistence on thinking longer-term about resource management, one of the core differences between Greens political philosophies that spread in the twentieth century, and more mainstream social democracy/state socialism worldviews, is the movement's emphasis on decentralisation and grassroots participatory democracy.

There's a long tradition (searching online, I was genuinely surprised by the number of papers on this topic) of green anarchist/eco-anarchist/social ecology critiques of the faith that state socialists place in centralised governments to sustainably manage and protect the environment. Green politics emerged in part out of some healthy tensions between anarchist and state socialist tendencies, and in Australia was also influenced by anti-colonial First Nations critiques of the nation-state.

Many Greens supporters recognised that rather than powerful nation-states and big corporations being diametrically opposed, the harm that large corporations perpetrate in their pursuit of profit arguably wouldn't be possible without nation-states using violence to defend those corporations' interests.

But within the Queensland Greens, and perhaps the Australian Greens more generally, it feels like the movement's tradition of critiquing 'big government' solutions has been ignored or largely forgotten.

Opening up that conversation will take time, and will be difficult in a context where a lot of key strategists and decision-makers are rushing from one election campaign to the next.

At the very least, we need to remind ourselves that there are numerous alternative models to meet a community's needs that don't depend upon heavily-centralised, top-down government administration, and also don't simply mean ceding more power to big, private corporations.

Perhaps we can dare to dream differently, and stretch our political imaginations a little further?

I would love it if you let me know what you think of this article. If you scroll down to the very bottom of this page, there's a button readers can use to leave comments.

Articles like this one are in part the product of conversations with many others in my community (particularly my partner Anna). Big thanks to all the people who've made time to chat with me about this stuff and help me flesh out my thoughts before I put fingers to keys.

This article is going to form part of a short series of pieces exploring the role of the Greens in the Australian political landscape, and unpacking what direction the party should be heading in. If you appreciate pieces like this being out there in the world, please consider signing up for a paid subscription...

Member discussion