Ironing out creases – West End’s cultural flattening

Kurilpa Derby, September 2012... A raucous, anarchic parade is rolling and dancing down Boundary Street in the heart of West End.

Our sharehouse at 120 Boundary is right in the middle of the action, above and behind the ground-floor shops. I’m perched on the roof, blasting notes on my sax in harmony with some musicians down on the footpath. Around me, housemates and guests drink tea or beer and wave at familiar faces in the parade. A steady stream of colourful friends and strangers flows between the street and our rooftop, climbing up into the sunlight via my bedroom window.

120 Boundary Street during the 2012 Kurilpa Derby

That was actually the day I first met a great friend of mine, Matt Hsu, who clambered up to say hi and eventually invited me to join the Mouldy Lovers – a big, frenetic 8-piece ska punk band that nurtured a solid following around inner-Brissie in those years, playing at house parties, street jams, festivals and the occasional poorly-paid bar gig.

In 2012, almost all the Mouldies lived in the 4101 postcode.

A decade later, none of us did.

One by one, we each moved further out as the rents climbed higher. And many of our favourite places to perform – both official venues and DIY gig spaces – closed down too.

This Mouldy Lovers music video features a lot of footage from our Boundary Street rooftop and the back courtyard where we held events

The closely linked suburbs of West End, South Brisbane and Highgate Hill all share the 4101 postcode. They’re often described by the Aboriginal word ‘Kurilpa’ (I’ll save commentary on that name’s precise meaning for a future article), and are now among the most expensive suburbs in the entire state.

Late last year, the selling prices of West End’s cheapest, crappiest 1-bedroom apartments climbed past $500 000, and Brisbane City Council ramped up its aggressive persecution of rough sleepers in public parks.

So I thought it timely to reflect on how the area’s recent evolution has shaped its cultural identity and wider influence.

While gentrification follows similar patterns across the world, each city’s version of this extractive, destructive phenomenon has its own idiosyncrasies and peculiarities, with specific variations from neighbourhood to neighbourhood.

Thinking about Kurilpa's recent evolution feels especially important because over the past two centuries, it has exerted a massive cultural and political influence on the wider Queensland colony – arguably more than any other Brisbane postcode. It’s been a hub and crucible of Aboriginal sovereignty movements, social justice campaigns, environmentalism, anti-capitalist political organising, and counter-cultural arts scenes. It’s also served as a landing point for successive waves of new migrants, and a petrie dish to experiment with different approaches to urban planning and development. Cultural changes within Kurilpa affect much more than the future of these suburbs alone.

Everyone’s insights about West End gentrification – including my own – are inevitably clouded by nostalgia. How much has the hood really changed, and how much of what feels different is actually just a reflection of my own ageing?

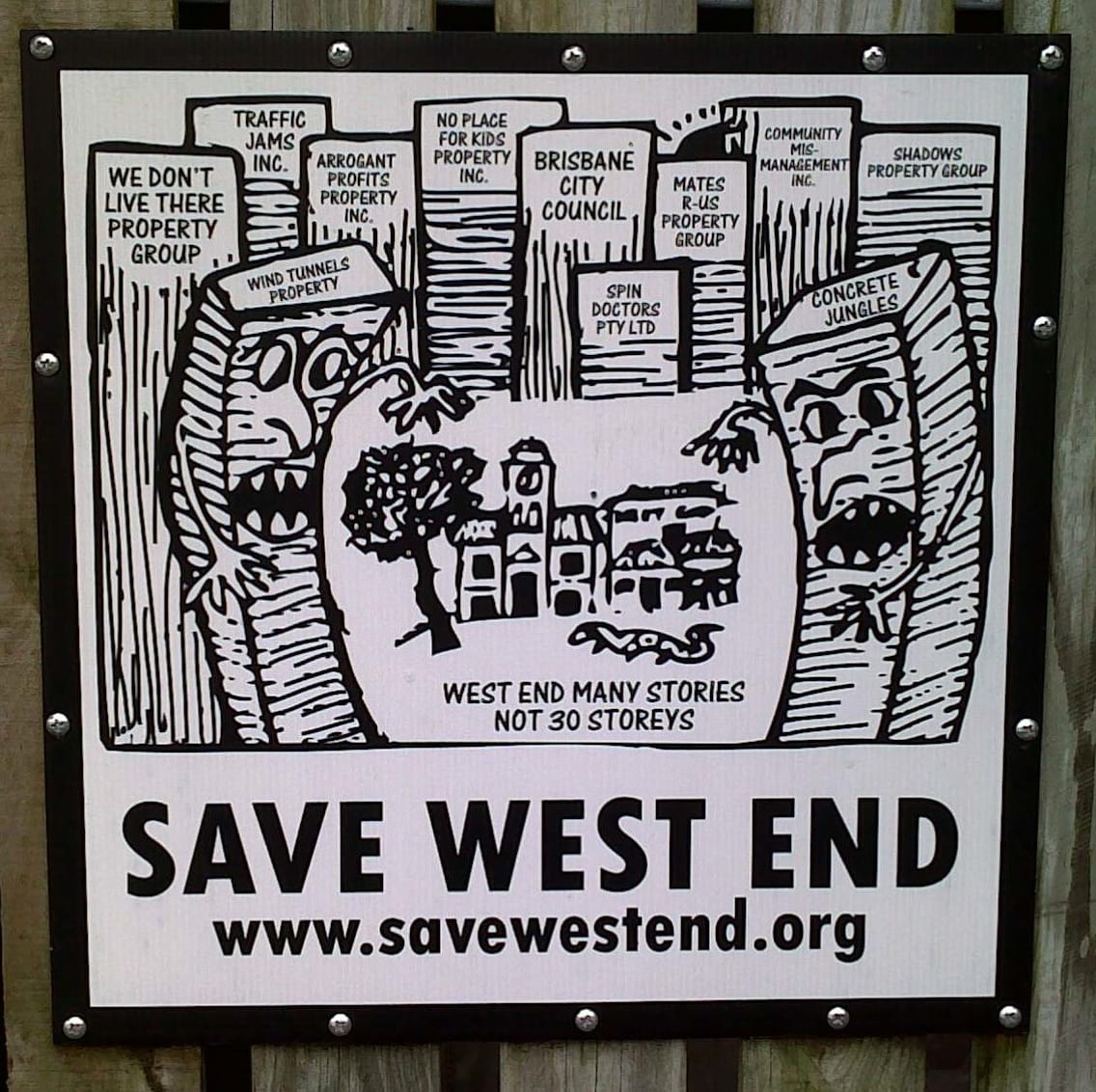

Instant Cafe, No Boundaries on Boundary was an anti-gentrification performing arts action organised by locals back in 1996

Every generation has “West End was different back in the day” stories about how the suburb used to be artsier or friendlier, and I’m cautious about romanticising the past.

I also don’t want to fall into the trap of describing the gentrification of Kurilpa as a recent thing – the suburb has always been in flux (for better or worse). As First Nations artists and researchers like Joel Spring and Lorna Munro have highlighted, 'colonisation' and 'gentrification' are – for many Aboriginal people – both different ways of describing and thinking about the same ongoing program of forcibly displacing and replacing people, fragmenting communities, enclosing and extracting value from the commons and carving up land/real estate to sell or rent for profit.

For tens of thousands of years, the Kurilpa peninsula was a mosaic of dense forest and wetlands where Aboriginal people lived more-or-less in balance with their ecosystem. But the land and its people were never static. The mix of vegetation would have shifted gradually over millennia, as did pre-Invasion First Nations people’s culture and lifestyles.

To argue that gentrification of West End ‘began’ at some specific point in history, or in discretely defined ‘waves,’ would be oversimplifying longer, more complex processes. But transformations over the past decade have been especially dramatic.

A rough overview of recent development patterns

One factor shaping 4101’s cultural evolution is that while many other inner-Brisbane suburbs redeveloped more gradually, development pressures in Kurilpa have felt more like a rubber band stretching tighter and tighter for many years, before finally snapping.

The 2008 global financial crisis, followed by Brisbane’s major flood in January 2011, perhaps contributed to high-density highrise development starting later in West End and South Brisbane than it otherwise might have. It took a while for property industry heavy hitters to find 4101 on a map. But once they did, they struck hard and fast.

The construction boom that kicked off around 2013 led to a very brief plateauing of rents and unit prices around 2017/2018, which developers then responded to by land-banking and delaying some projects. They’ve continued to build in the 2020s, but are now strategically drip-feeding new units onto the market so as not to deflate prices.

Many new apartments are cramped and poorly designed, with minimal natural light and airflow. Others are large and luxurious, with river views or private rooftop gardens, and only affordable for the wealthiest newcomers.

Most of these highrise development projects were on industrial and commercial sites. With a few notable exceptions, they didn’t directly displace many existing residents, but did reduce availability of old warehouses and other adaptable spaces previously used for gig venues, rehearsal rooms, artist studios, markets and circular economy projects.

Rezoning for highrise meant land values across Kurilpa shot up. Even on streets that weren't up-zoned, mouldy, leaky-roof rental houses whose only toilet was a backyard outhouse were suddenly worth $2 million or $3 million due to their notional redevelopment potential.

Meanwhile, relaxation of the city council demolition controls and character protection rules applying to older homes fertilised another form of gentrification, with more boarding houses and ageing worker cottages renovated into mcmansions that now rent and sell for much higher prices.

This accelerated from 2020 onwards, due in part to covid-related government ‘HomeBuilder’ stimulus programs, as well as shifting preferences among middeclass residents for more private space, and has arguably had a bigger, more immediate direct impact in displacing lower-income renters from the inner-south side.

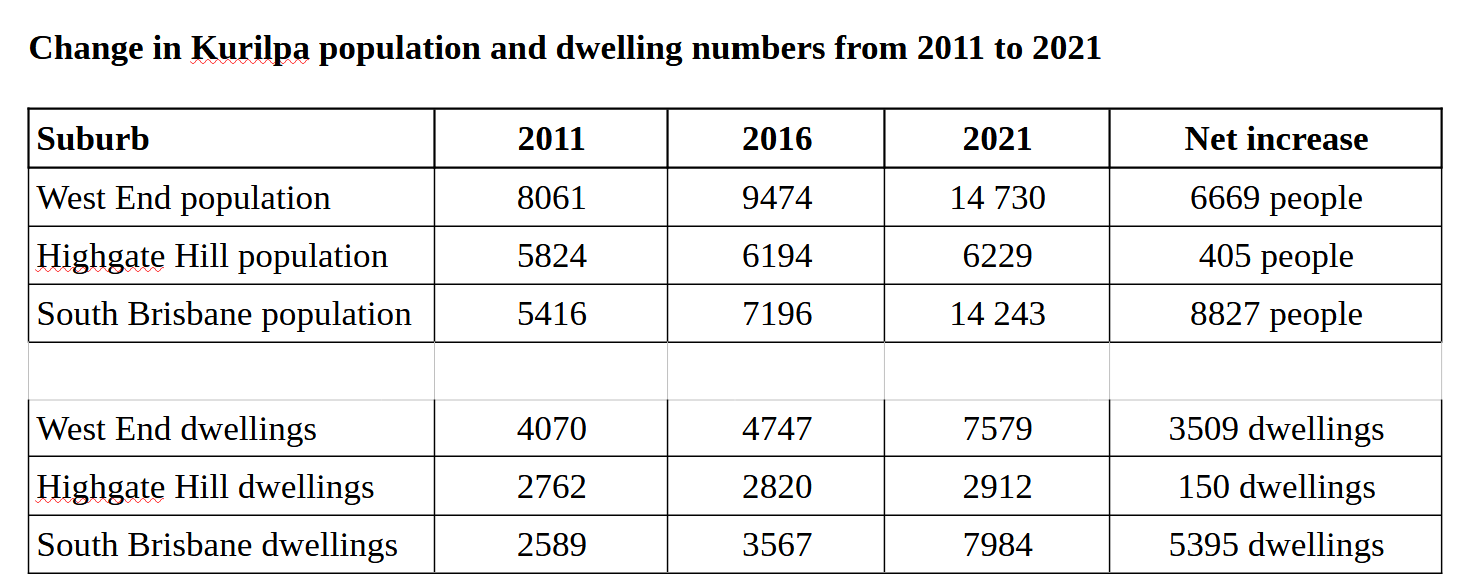

Census data shows how quickly population (and dwelling numbers) increased from 2011 to 2021 in South Brisbane and West End, primarily due to construction of new apartments on floodprone industrial sites (which for decades had been considered unsuitable for residential housing). Meanwhile, neighbouring Highgate Hill’s population grew slowly, with increases from the handful of new apartment projects partially offset by the number of renovated boarding houses and sharehouses that had previously accommodated 6+ adults, but now contain at most two adult residents and maybe one or two children.

This building on Emily Street in Highgate Hill was renovated from a 10-person boarding house into a single large residential home which now only houses a couple of residents - at least it retains more character than some of the 'boomer tombs' popping up around the neighbourhood

Throughout this period, many older, local small businesses like hardware stores, green grocers, tailors and bakeries were also replaced by cafes, bars, and real estate agencies. But these changes to the local business mix haven’t necessarily been as consistent as gentrification tropes from the US or UK might lead us to expect (perhaps another future article topic).

The next census in 2026 will likely show that Kurilpa’s population growth hasn’t been quite as fast since covid. But more crucially, will probably also show a continued decline in the number of young adults living in sharehouses, and more abrupt changes in residents’ income levels.

I described all this as a snapping rubber band because it wasn’t just a case of rents and prices rising gradually but relentlessly (as occurred over previous decades). In barely ten years, profit-driven redevelopment and renovation has completely changed how thousands of properties across Kurilpa are used – warehouses into luxury apartments, boarding houses into mcmansions, low-rent sharehouses into high-rent yuppie cribs and boomer tombs.

Without boring you with too many stats, the broad outcome is that in less than a decade, Kurilpa has almost doubled in population, while losing a lot of cheaper housing and many of the adaptable urban spaces that artists and counter-cultural organisers previously utilised.

So what about culture?

I don’t buy into reductive narratives blaming artists and community organisers for gentrification – they're generally not the ones treating housing as a commodity to make a profit from, or jacking up the rent. But I’m particularly interested in unpacking some of the subtler elements of how the culture of West End is changing, especially in terms of the experiences of young adults who are into art and music.

Kurilpa’s cultural and artistic changes have been much subtler and more gradual than the sudden appearance of new highrises. It’s a little harder to put my finger on exactly what’s shifted... Maybe it's not as weird or adventurous as it used to be?

4101 is rightly still recognised widely as one of Queensland’s ‘artsiest’ postcodes. Alongside the major galleries, museums and theatres, there are plenty of ‘creative industry’ businesses like film-makers and graphic design studios. And if a visitor asked me where Brisbane’s most bohemian, alternative suburb was, I’d probably still send them to West End. But I feel like there's less experimentation and innovation that there used to be. Maybe there's not as much cross-cultural, cross-genre and interdisciplinary work coming out of the inner-south-side these days?

In many respects, artistic communities and subcultures have been more resilient and persistent in West End than in other inner-Brisbane suburbs (e.g. Paddington, New Farm) that were also once well-known as hubs for the arts and counter-culture. Many musicians, activists, DIY event organisers and permaculture hippies seem to have hung on in 4101 a little longer, often by cramming extra rent-payers into already-bulging sharehouses, or by contenting themselves with a smaller unit in a 1970s brick six-pack. People tolerated progressively crappier housing conditions – paying higher and higher rents for the same deteriorating homes – in order to remain close to the action.

Nowadays, neighbouring Woolloongabba is home to just as many venues and event spaces specialising in local live music as Kurilpa is.

Plenty of younger adults who are interested in music and the arts still live in West End, South Brisbane and Highgate Hill. And lots of amazing local community events and projects continue today, most notably Kurilpa Derby, Laura Street Festival and Meanjin Reggae Festival. And many older artists, musicians and writers who purchased homes before prices skyrocketed continue to live locally (to some extent masking the forced exodus of younger creatives).

But life for your average 25-year-old wannabe musician, artist or writer living in 4101 today is markedly different to when I first moved into the inner-south side in my early twenties.

Then vs now: Rent pressures and the loss of flexible time

Living in a Highgate Hill sharehouse as a uni student in 2011, I could sustainably cover my rent and other regular expenses from Youth Allowance alone. Money was tight – I mostly lived off lentils and chickpea curry, cycled for transport, never bought alcohol or dined out (unless I was table diving) and borrowed textbooks from the university library rather than buying my own. But I was fortunate to be able to get by without taking a paid job in addition to studying.

My old Dornoch Terrace sharehouse looks very different today (at least the new owners didn't put up a 2-metre boundary wall) - the two sharehouses next door were demolished by an investor who has left the blocks empty for a decade, waiting for land prices to rise

When I wasn’t attending classes at UQ, I had plenty of time for jamming and seeing gigs, long catch-ups with friends in the park across the road, sitting by the river to write poems and song lyrics, or jumping the fence to sneak into the swimming pool at 165 Dornoch Terrace (that house sat empty for a long time, but the pool was always well-maintained).

After I graduated, and my partner Anna and I moved into the sharehouse in the middle of Boundary Street, I was able to cover my rent and bills by busking for just three or four hours a week. If I was saving for a music festival or wanted to see a ticketed gig on the weekend, I might up my busking work to five or six hours. Friends who part-timed as baristas or uni tutors or gardeners or shelf-stackers had similarly light work schedules. Some worked more, and spent their earnings on drugs or booze.

Having so much time to myself gave me the flexibility to co-run voluntary projects like Courtyard Conspiracy – a weekly community gig/gallery night that we hosted in our backyard on Monday evenings. Because we had cheap rent, and the other musicians and artists who shared their work in the courtyard also had low housing costs and were happy to play for free, we didn’t feel obliged to charge an entry fee.

The abundance of flexible time meant that in the same period, in addition to curating the Courtyard Conspiracy art gallery, Anna also helped establish Brisbane Free University, which ran fortnightly public lectures in Westpac Bank’s underground carpark (today part of the West Village site), and started producing a weekly radio show on 4ZZZ.

I was regularly rehearsing and gigging with two different bands, performing poetry at various cafes around West End, helping carry tables and wash dishes for Food Not Bombs most Fridays, volunteering with other periodic events like Laura Street Festival, defending a humble rooftop veggie garden from crows and possums (with mixed success), getting to know Murri activists who were organising out of Musgrave Park, and regularly attending anti-Campbell Newman protests in the city.

Looking back on it now, I’m amazed at how many different non-profit projects we were involved in simultaneously. It was all possible because so many artists and activists could afford to live close to each other, without the burden of high rents forcing us to work long hours in exhausting jobs. This wasn’t merely a case of a couple dozen creators whose privilege allowed them to organise free events – thousands of (mostly younger) people who lived across the inner-city all had the time to get involved in local projects and events on a regular basis, and actively participate in a bubbling counter-cultural community.

In 2025, that lifestyle simply isn’t available to most young adults renting in Brisbane’s inner-south side. Rents are too high, food’s too expensive, welfare payments and wages have barely risen, and everyone’s a lot more nervous about saving for an increasingly precarious future.

But fifteen or twenty years ago, the kind of life I’ve described above was reasonably common in 4101.

More people had more time to make (and consume) music or art or subversive political zines. And artists were (generally) less concerned about whether their work would be ‘commercially viable’ and attractive to a paying audience.

This, perhaps, is one of the biggest cultural changes in West End in recent years, but not something that Census data about ‘Occupation’ and ‘Industry of Employment’ is able to meaningfully record and reflect. The line between ‘creative professionals,’ and the hobbyists who can only find a couple hours a week for their passion project, has become starker. Fewer people seem to have time for wackiness and experimentation.

The same is perhaps true for other related fields such as political organising or community development work. If you’re paying market rent in West End, you can probably only find a couple hours a week to volunteer on activist and community projects. So more of this work is today undertaken by a smaller cohort of paid specialists, with much of the wider community reduced to the role of passive consumer or service recipient. Even if you could budget ruthlessly to cover rent and bills while only working 10 hours a week, most landlords and agents wouldn't rent to you.

The types of people who never earned much money for their art or community organising, but still put lots of time into it, have either dispersed to cheaper parts of the world (Anna and I moved to East Brisbane, and then onto a houseboat), or taken up more paid work shifts in other fields, limiting their participation and creativity. And when you move further out, the extra travel time adds up. Alongside this, social norms have also changed.

Too scared to break rules?

One of the subtler but most significant shifts has been the slow death of the subversive, rebellious, punk ethos that accompanied a lot of inner-city communal projects and counter-cultural arts scenes, and bled out into the wider community.

This was the DIY, anti-authoritarian, try-it-even-if-the-council-says-you-can't attitude that informed my activism as a city councillor, and lives on in projects like Food Not Bombs or Growing Forward's Kurilpa Commons. Don't stress too much about official traffic regulations when your busking audience flows onto the street... Don't ask where all those milk crates came from... And definitely don't call the cops!

Early 2000s West End had a stronger critique of state surveillance, over-regulation and centralised governance in general, which was shared and reinforced particularly by Aboriginal residents and many new migrants. Protest was assumed to be a good thing until proven otherwise. This anti-establishment attitude was an important counter-weight to the mindless conformity radiating out of Brisbane's Central Business District, and the authoritarianism of Queensland's dominant political culture.

Gentrification has brought increased surveillance – more CCTV cameras, more police patrols, more invasive rental application processes – and the increasingly upper-middle-class population is becoming more compliant (and more likely to call in noise complaints). The public servants and private sector white collar workers now clearly outnumber the hippies, punks, and working-class shit-stirrers, so at a community-wide level, the collective appetite for dissidence and disorder is much weaker.

This manifests both in more rule-abiding (and thus costly) approaches to event organising, but also in diminishing scepticism towards the nation-state. Progressive politics within South Brisbane now seems more oriented towards statist social democracy than anarchist political philosophies, bringing Kurilpa more into line with the rest of the city.

We're perhaps seeing this play out in the way that many middle-class 4101 voters are today less comfortable with their Greens elected representatives supporting protests and adopting more robust negotiating approaches in parliament. The ramifications of West End losing its instinctive "fuck you I won't do what you tell me!" impulse could be deep and lasting for Australian politics.

Rebels are increasingly frowned upon as 'divisive.' Rules are presumed to be legitimate. The rough edges have been sanded down.

The slow death of communalism

"I believe that Expo will have an effect on the little people in my electorate. As a result of Expo, rates and rents will rise. More than 50 per cent of the people in South Brisbane and West End live in rented accommodation. They will be pushed out.

What will be left there? There will be very expensive, high-rise development. In many ways, I think it will become a ghetto. It will be a concrete jungle with barricaded doors.

People will have to speak into a microphone before they will be able to enter the high-rise apartments."

- Jim Fouras, Member for South Brisbane, Queensland Parliament Hansard, 30 November, 1983 (Mr Fouras ultimately toed the Labor party line and supported hosting the 1988 World Expo in South Brisbane.)

In the West End I got to know as a young adult, sharing resources and helping out neighbours felt more common than in the suburbs I’d previously lived in (West Chermside and Indooroopilly), and more normalised than it is today. Mutual aid obviously hasn’t ceased altogether, but like almost everywhere in Australia, the community has, I think, become more individualistic and atomised. Historically, 4101 residents were arguably more socially connected and interdependent than most outer-suburban Brisbane residents, so the shift towards individualism feels more pronounced in the inner-city.

More young people now live in smaller apartments, with one or two housemates at most. The larger sharehouses where six... seven... sometimes ten people lived communally, and learned from each other how to share kitchens and bathrooms and cleaning rosters, are much rarer.

I don't want to over-romanticise sharehousing. I know people have different experiences of it. But cohousing taught me a lot about compromise, negotiation and interpersonal conflict resolution. Maybe there's less of that these days?

People might still know the names of a few people on their street or in their building, and in some cases have close social relationships with them (the 2022 floods actually strengthened this somewhat). But these days, if the average West Ender who doesn’t own a vehicle needs to drive somewhere, they’re more likely to hire an Uber than ask to borrow their neighbour’s car.

I even noticed this shift during my 7 years as a city councillor. Between 2016 and 2023, I saw a change in the patterns of neighbourhood disputes coming across my desk. Debates about street parking rules, trees growing over boundary fences, and conflicting uses of public parks, all became more adversarial. This is partly just a consequence of the council cramming more people into a neighbourhood without investing enough in public transport and community facilities. But it also felt like residents were losing the ability to respectfully work things out among themselves, and were increasingly inclined to complain to the council or police, demanding a third party arbiter rule in their favour.

I should stress that these are just subjective impressions and general trends I've noticed. There are still plenty of communally-minded people living right across Kurilpa, and heaps of stories of neighbours helping each other out. But there's also a lot of fear of strangers, which I think is partly reinforced by the suburb's changing built form.

While much has been made about the gradual loss of Brisbane backyards, perhaps a more significant casualty of gentrification in West End and Highgate Hill has been the front yard spaces – the semi-private, semi-public areas transitioning from the street into people's homes. Many of the footpaths, yards, driveways and front verandas and staircases where people used to interact spontaneously with neighbours and passing strangers have been have been blocked by high walls, locked gates and intercom security systems, while the foyers of most new apartment towers are closed to the general public. Even apartment tower letterboxes are sometimes behind locked doors.

The buildings might be closer together, but many residents seem further apart from one another than ever before.

A side note on cultural diversity

The symbiotic relationships between changes to built form and cultural norms also seem to be playing out in the experiences of newer migrant communities.

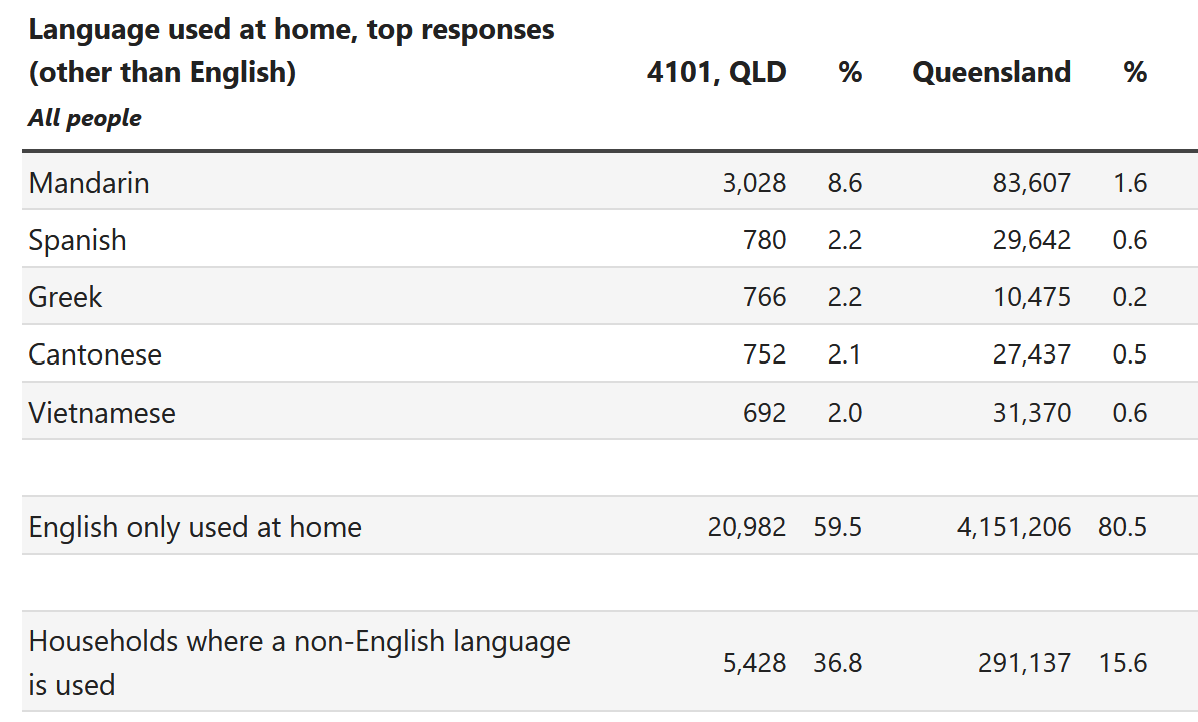

Happily, despite ongoing gentrification, Kurilpa is (statistically speaking) even more ethnically and linguistically diverse than it was 10 or 15 years ago.

At the time of the last Census, the proportion of 4101 households where a non-English language is spoken had climbed to 36.8%, way above the statewide average of 15.6%.

According to the 2021 Census (conducted while covid travel restrictions were still in place, but after many short-term migrants and international students had returned home), there are now more Spanish speakers in Kurilpa than Greek speakers, and a whopping 13.5% of residents have Chinese ancestry. Crucially though, only 6.7% of 4101 residents were actually born in China, and a large proportion of Kurilpa's Mandarin and Cantonese-speaking residents seem to be Australian-born young adults with Chinese heritage.

Even though on paper, the suburb is becoming more culturally diverse, that diversity doesn't seem to be reflected as obviously in the physical presence of cultural institutions.

Even at its peak a few decades ago, Kurilpa's Greek-ancestry population was never as large as the present-day Chinese-ancestry population. But whereas Vietnamese, Greek and Lebanese migrants in the 20th century opened shops on the main street, formed local associations, established community centres, churches, clubs, and even festivals like Paniyiri, the Chinese migrant presence in Kurilpa seems subtler (to me at least).

Maybe this is because in the 21st century, new migrants are able to connect online and maintain closer links to their countries of origin. Or perhaps it's because Chinese West Enders also have existing cultural hubs such as Sunnybank to orient towards. And of course, buying up inner-city land to start a community centre is much more expensive today than it was 50 years ago.

But I wonder whether the above-mentioned shifts in 4101's dominant culture – less heterodox, more individualistic, atomised, and rule-abiding – is also shaping the way different ethnic communities express and practice culture, and the extent to which they influence each other and the dominant culture. Is the inner-south side becoming more culturally siloed than it was a few decades ago?

If gentrification has reduced the availability of low-cost third spaces, and walled off the front yard (strengthening the boundary between the private residential sphere and the increasingly-surveilled public sphere), perhaps ethnic cultural expressions are now more restricted to inside people's homes?

Murris holding on

Despite everything the colony has thrown at them, the First Nations cultural and political presence remains strong in Kurilpa, from Triple A Murri Radio up on Ambleside Street, to hubs like Bowman Johnson Hostel, to ongoing community organising in Jagera Hall and Musgrave Park. But most of the people who drive these projects and work for these organisations can't secure rentals or buy homes in the area.

I don't think it's my place to write about how recent changes have impacted Kurilpa's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, but I suspect the picture is more nuanced than simplistic gentrification narratives might suggest.

Skimming through Census data, I was interested to note that after declining steadily throughout the 2000s, both the percentage and total number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander residents in Kurilpa has recovered slightly, from 234 First Nations residents (1% of total population) in 2016 up to 482 First Nations residents (1.4% of total population) in 2021. However compared to a couple decades ago, the mix seems to have shifted slightly, with fewer multi-generational Aboriginal families, and more tertiary-educated young adults (it's also hard to say how much of this increase might be due to more people identifying as Indigenous in the last census).

Certain public spaces around 4101 are still regularly used by First Nations people – mostly in the precincts that haven't redeveloped recently. Aboriginal businesses and community projects are dotted throughout Kurilpa, but you won't find many Murris hanging out on in front of the new apartments along Montague Road, or in the heavily-surveilled gardens of West Village. They mostly stick to Musgrave Park, and the older, less gentrified stretches of Boundary Street, reminding those of us who stop to listen that any non-Indigenous West Enders who profess to be concerned about newcomers 'taking over' or 'changing the culture of the area' would do well to look in the mirror.

The point of all this is not to argue strongly that Kurilpa has changed for better or worse. But simply to document some of what I feel has been lost, and perhaps prompt conversations about whether any of it is worth recovering.

Rent caps and more public housing would reduce housing stress and perhaps restore the time-abundance that many of us enjoyed in the inner-city a decade or two ago.

Creating more non-profit third spaces where different cultures and sub-cultures can mingle and cross-pollinate would likely help diversify and reinvigorate 4101's artistic ecosystem, and maybe support greater community connectedness and more mutual aid.

But the counter-cultural rebelliousness and underlying scepticism of authority might be harder to revive. It feels like even the ibis and bush turkeys are better behaved these days.

That deference to establishment power structures worries me the most. If young West Enders are no longer encouraged to think critically about hierarchy and imagine different, more radical futures, where will those conversations happen? And where in our city will alternative hubs of resistance to oppression be able to form?

If actual nazis ever come marching down Boundary Street, will anyone still be ready to throw a paint bomb at them?

Addendum: While I thought (or at least hoped) this came through clearly in the piece, I've decided I need to clarify I'm not arguing that "West End should go back to the way it was" or that "everything was better 10 (or 20 or 30) years ago." There's still heaps going on in 4101, and a really broad range of cultures and community projects bubbling away. I'm simply highlighting a few elements that seem to have changed, and prompting readers to consider what the broader social and political ramifications of those changes might be. Please do let me know what you think of all this via the comments!

Thanks so much for reading! If you appreciate this kind of writing being publicly available, please support it by signing up for a paid subscription.

It means a lot to me that so many people are interested in what I have to say, but it takes time to put thoughts down on paper, so if you can afford $1/week to support independent commentary and analysis like this, I'd be incredibly grateful!

Member discussion