Why have the Greens 'suddenly' started winning seats in Queensland?

In the space of a couple days, a lot of journalists and political commentators (including some Greens members from down south) have apparently become experts on the growing electoral success of the Greens in Queensland, despite the fact that very few of them seemed to have paid close attention to what’s been happening here over the past 7 or 8 years.

Many of these explanations (particularly from major party supporters) are hilariously simplistic, maybe because some people are trying to convince themselves that there’s an easy, straightforward way to counteract what’s happened. They sound more like wishful thinking than robust analysis… “Oh the Liberals lost because we didn’t put forward enough strong female candidates!” (Yeah sure mate… That might be part of it, but the collapse in both the major parties’ primary votes is far more fundamental, long-term and chronic.)

Greens victories in the senate and multiple lower house seats around Brisbane might seem like they’ve come out of nowhere, or that they’re purely attributable to concerns about climate change. But there’s way more going on here.

At all levels of government, the Queensland Greens vote has been rising steadily – particularly in Brisbane – in consecutive elections since 2016, but it hadn’t resulted in us actually winning many seats. We came close to snagging four more Brisbane wards in the March 2020 local government elections, but the Greens vote was dampened by the arrival of covid and associated disruptions (voter turnout was under 80% - and was especially low in electorates with higher proportions of young adults). Similarly, the overall Greens vote wasn’t great in the November 2020 Queensland state election, apparently because a lot of progressive voters wanted to signal support for Palaszczuk’s handling of the pandemic. The muted results in these two most recent elections partially hides the longer-term general trend of growing Greens support in Brisbane, which is perhaps why some people didn’t predict this result in 2022.

Our federal election victories didn’t come out of nowhere. They’re the product of years of patient, dogged organising and capacity-building.

General swings vs bigger surges

Nationwide, the Greens vote seems to have increased by about 1.4%. I suspect much of that general swing is connected to climate change, corruption, women’s justice, maybe refugee rights etc.

That positive swing is also partially attributable to the broader trend of more young Greens-leaning people turning 18 and enrolling to vote, while older, conservative voters pass away. A lot of those school kids who marched in the street as part of climate strikes a couple of years ago are now adults, and are moving to the inner-city… I don’t think many of them are voting for parties who support digging new coal mines or endlessly propping up house prices.

But the additional swings of 5% to 10% that we’ve seen in multiple electorates are well ahead of the national trend, and contrast markedly with progressive inner-Melbourne seats like Wills and Higgins, where the Greens vote barely moved (despite the absence of strong independent campaigns).

The other important piece of the puzzle – which might be a hard pill for some Queensland Greens members to swallow – is that the headline-grabbing growth in Greens support seems to have been much more concentrated in Greater Brisbane and a few other pockets of South-East Queensland than in the rest of the state.

The Greens (myself included) really want to believe our messages and vision are appealing to voters across Queensland and that we aren’t just a party of the inner-city. And we did see healthy swings in Brisbane’s middle and outer suburbs, which are demographically quite different from the inner-city. Electorates like Ryan stretch all the way out to Ferny Grove and Upper Brookfield on the city’s outer fringe. They are not purely inner-city electorates.

Encouragingly, we’ve also seen a Greens primary vote increase of 1% to 2% across most of the rest of the state. But this isn’t markedly different to average swings across Australia. Unfortunately, contrary to some commentary and wishful thinking, there was not a ‘massive’ swing to the Greens in regional Queensland. Choosing a ‘regional’ lead senate candidate, Penny Allman-Payne (currently based in Gladstone), might have bumped up our vote outside of SEQ slightly, but it doesn’t appear to have had a major effect.

And while we gained respectable swings in outer-suburban Brisbane, the Greens vote only increased modestly in most seats on the Gold and Sunshine Coasts. Our policy platform might have wide appeal to voters across the state, but for various reasons, it’s not yet getting through to them or winning them over.

So on closer inspection, the ‘Greens surge’ in Queensland actually looks like a small general nationwide increase in the Greens vote, coupled with much bigger swings in Brisbane itself that bump up the state average.

It would take too long to offer a full analytical explanation of this growing Brisbane vote, and I won’t pretend to understand all the variables and voter motivations on the ground in our key seats. But let’s start by ruling out the explanations that are not particularly credible…

“Lots of Greens voters moved up from down south”

Not quite. Thousands of people have certainly moved up to Queensland from the southern states lately. You might expect that demographically, these people would be younger and more inclined to vote progressive. But we don’t really know for sure.

In my electorate, I’ve certainly met young, progressive, Greens-leaning southerners who’ve moved north, but I’ve also encountered older, wealthier, more conservative people who’ve made the move.

As mentioned above, most seats on the Sunshine Coast and Gold Coast had comparatively small swings to the Greens, even though these regions have reportedly also had quite a large influx of interstate migrants.

In the context of a population of millions, the total number of people who’ve moved north simply is not significant enough to explain such big swings in Brisbane. The Greens vote has increased by tens of thousands. Mathematically speaking, it would be silly to attribute that to interstate migration alone.

There were no ‘teal’ independents competing in Queensland

True. But why didn’t strong independent campaigns emerge in Liberal-held seats like Ryan or Brisbane?

Down south, a lot of people who weren’t particularly impressed with either major party decided to run as independents (or to actively campaign for them) because there was no existing alternative party or grouping that seemed to have a credible chance of success. Meanwhile here in Brisbane, the Greens had been picking up momentum with big swings on council plus a couple of high-profile state election victories.

The steady growth of the Greens in Brisbane meant that for anyone who was unhappy with major party inaction on climate change, there was already a clear alternative political force to get behind.

Rather than saying “The Greens did better in Queensland because there were no centrist independents” we should recognise that there were no strong campaigns by centrist independents in Brisbane precisely because the Greens were doing better.

No-one cares about an ICAC

Ok maybe ‘no-one’ is an exaggeration. But based on all the conversations I’ve been having over the past few months at community events, in private meetings with residents, and at the polling booths, I’m not at all convinced that demands for a federal ICAC were a major vote-swinger in Brisbane.

Obviously there are lots of politically engaged people who’d like to see a federal anti-corruption commission. But such demands can feel somewhat abstract and technocratic for disengaged swing voters who are worried about affording childcare and paying the rent.

We definitely still need an Independent Commission Against Corruption at the federal level, but the reality is that this isn't the main issue changing most people's voting intentions.

It was the floods!

Maybe a tiny little bit. But not necessarily in the way you think.

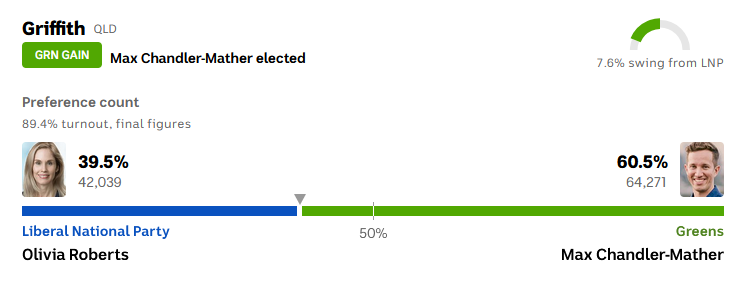

As big Greens swings started coming in on election night, a couple of commentators started pointing out that they were all in flood-affected areas along the Brisbane River. This is only partially true. Some parts of Ryan, Griffith, Brisbane, Moreton and Bonner, were indeed smashed by flooding. But most suburbs in these electorates were only marginally impacted, and a booth-by-booth analysis doesn’t show a correlation between flood impacts and positive Green swings within those electorates. With the arguable exception of Ipswich (Blair), other parts of the state that were flooded much worse than Brisbane didn’t see similar big Green swings.

While we may wish it were otherwise, major climate change-related disasters don’t automatically lead to a rising Greens vote.

But apart from reinforcing the realities of global warming, I think the floods did help by highlighting the broader, deeper failures of the existing social order, and prime more people for conversations about structural and political change. For some of the people I spoke to at the polling booths, it wasn’t so much climate change that had them worried, but the nation-state’s demonstrated inability and unwillingness to offer meaningful support during crisis.

This is a subtle but important distinction. Flooding impacts are very uneven, and the number of people directly and severely affected might only be a small proportion of an electorate. But such disasters can be a launching point for broader political discussions, and an excuse to connect with the community.

The greater significance of the February flood was that it created an opportunity for the Greens to demonstrate a practical commitment to helping our local communities. Much of the flood clean-up in suburbs like West End and East Brisbane was undertaken by volunteers organised through Greens networks, and particularly by the Griffith election campaign team. And because we weren’t beholden to government talking points, elected Greens reps (me, Michael and Amy) were also providing more detailed and useful public information about flood risks and recovery logistics, highlighting the advantage of having a hard-working Greens MP or councillor.

This brings me to one of the key overlooked factors that definitely did contribute to the Greens’ success in Brissie…

We are closely linked to grassroots community organising and activism

Pretty much wherever you go in Australia, Greens members and supporters are active in social justice and environmental activism campaigns, from bushcare groups to refugee rights street marches. But I think in Brisbane we may have evolved a slightly better (but still imperfect) model of solidarity and co-organising that uses party and elected rep resources to more meaningfully and actively support projects and struggles without co-opting them.

I still worry that our big electoral campaigns are drawing away too much volunteer energy from other grassroots community struggles, but at least we’re maintaining a more solid connection to them.

In many cases, the very same people who are starting community gardens, putting on street festivals, fundraising for refugee housing or organising climate justice protests are also coming along to Greens branch meetings and handing out flyers on election day. There’s very little distance between many of Brisbane’s activist communities and the Greens as an electoral party, because so many of us have a foot in both spaces. At election time, this support for grassroots struggle translates to more volunteers than Labor and the Liberals combined (within inner-Brisbane at least), and a deeper, more nuanced understanding of what the community cares about.

A separate but related factor may be that when it comes to activism, Brisbane has been a pretty radical city over the last few years.

It’s hard for me to draw accurate comparisons to Australia’s other capitals, so I don’t want to overstate this point. But I suspect that Brissie-based activist movements are generally more radical, and more willing to directly challenge state power front-on. They are less influenced by the kinds of liberal reformism and weak-willed de-escalatory thinking that’s normalised and disseminated by big NGOs based in Sydney and Melbourne. While our overall numbers might sometimes be smaller, we get shit done and we don’t shy from conflict.

There’s been a lot of really staunch resistance and struggle here on the streets of Brisbane that has successfully drawn wider public attention to injustices and oppression perpetrated by the colonial nation-state, including by the Queensland Labor Party. This has benefited the Greens electorally, and mustn’t be overlooked.

A lot of Queensland Greens analysis and commentary will likely focus on doorknocking and our effectiveness at one-on-one political conversations. But we can’t ignore the significant value of all the other kinds of movement-building, community organising and civil disobedience that’s been happening parallel to our election campaigns, which creates more political space for the Greens as an electoral force (essentially a ‘radical flank’ effect) while also serving as a strong social base that can (hopefully) hold elected reps accountable.

Political education = effective campaigners

Another key element (which I suspect is more prominent among the Brisbane Greens branches than in other parts of the country) is the stronger emphasis on political education and collective strategising. Amy, Michael and I look for opportunities to involve our wider support base in public discussions about policy and political strategy, organising forums and info sessions about big stuff like colonialism and imperialism, the party’s position on controversial topics like covid lockdowns, and the philosophical framework that informs our stance on issues like housing and urban development.

Before elections, key campaigns also put heaps of time into making sure more of our supporters understand our political vision and policy platform, with multiple campaign intro sessions for new volunteers, public lectures, and post-doorknock debriefs functioning as mini political education forums in their own right. In contrast, I’ve heard that many Labor campaigns offered no meaningful training to new doorknock volunteers at all. Our volunteers know what they’re talking about. Theirs don’t.

All of this combines to create a growing layer of highly engaged volunteers who can discourse much more deeply with people about why they should vote Greens. Meanwhile, a lot of major party campaigners seem unable to do much more than parrot slogans. This distinction was starkly visible at the prepoll booths and on election day. Greens volunteers who’d had far more training and experience at one-on-one political conversations were able to engage meaningfully with undecided voters, listen to their concerns and convince them to put the Greens first.

On election day this year, I spent most of my time at the Kangaroo Point polling booth. I met a lot of residents who weren’t loyal to any particular party, and still felt really uncertain about the choice they were about to make.

For almost 10 hours, I spoke to dozens and dozens of people, many of whom were either completely undecided, or who were leaning towards one of the major parties but open to being persuaded otherwise. Without exaggeration, I would conservatively estimate that I was swinging about 5 votes per hour purely through one-on-one conversations (plus locking in many more).

At the Brisbane City Hall prepoll booth on the Friday evening before the election, there was an even higher proportion of swing voters from across Brisbane, and I’d estimate that I was swinging closer to 7 or 8 votes per hour.

Those numbers might not sound like much in the context of federal electorates with 120 000+ voters, until you remember that throughout the 10-hour election day voting period, at almost every single booth in our key Brisbane seats, there would have been two or three equally-effective volunteers on shift at all times (backed up by many more volunteers who weren’t quite as experienced but could still smile and hand out flyers).

An electorate like Griffith has around 20 larger polling booths (and another 10 to 15 smaller ones). So with two or three experienced campaigners at each of those major booths swinging 4 or 5 votes per hour (votes that would otherwise have gone to one of the major parties), that potentially amounts to a swing of 2000 to 4000 votes right there on election day, plus a couple thousand more at the prepoll booths. This maths is obviously rough, but the general conclusion is worth paying attention to.

Thanks to a robust and multi-faceted emphasis on political education, Greens campaigners in key Brisbane seats have become devastatingly effective at changing voters’ minds if we get the chance to talk to them one-on-one.

A radical orientation

Ultimately, the main reason we can swing so many voters and motivate more volunteers to campaign for us is that people genuinely like what we’re offering.

In the past few years, the Australian Greens have shifted to campaigning on a broader social democracy platform. We’ve been talking more explicitly about how our calls for climate justice and social justice connect directly to higher taxes on the mega-rich and increased spending on public housing, healthcare, education etc. rather than allowing ourselves to be pigeonholed as caring exclusively about koalas and trees.

I would argue that this shift has been led by the Queensland Greens, and flows directly from our initial experiments with bolder policy platforms in the 2016 Gabba Ward council campaign and the 2017 Queensland state campaign.

For years, too many people in the Greens (and in progressive circles more generally) have uncritically swallowed the myth that we can’t be too radical or we will put off ‘centrist’ voters. But that conclusion doesn’t stack up to the experience from successive campaigns in Brissie.

In electorates like Griffith and Ryan, we were talking openly and confidently about capping rents and scrapping negative gearing. This certainly put off a few property investors from voting for us, but it also helped us win over heaps of people who were on the fence between Greens and Labor, or indeed between Greens and the Liberals. Bold platforms based on taxing the mega-wealthy, discouraging property investment and redistributing wealth towards social services and public facilities are extremely popular with the majority of voters.

But the swings in Queensland aren’t just down to this broader policy platform. We have an underlying vision and ethos that seems to resonate particularly strongly with voters who are disillusioned with the major parties. Rather than settling for narrow parameters of debate and contenting ourselves with liberal reformism, we continually push for deeper change and demand more of the political establishment. When the major parties reject the ideas we’re advocating, we support protests and other forms of activism to ramp up the pressure.

During Max’s campaign in Griffith, a lot of Bulimba residents articulated concerns about a major development proposal on flood-prone land. While other progressive campaigns would have contented themselves with encouraging people to make written submissions to the council that are inevitably ignored, Max’s campaign didn’t settle for that. They drew on community networks and worked with residents to establish a community garden right in the path of the proposed road that was to lead into the new subdivision (without asking permission from the authorities). Later, the campaign distributed produce from the garden as part of covid lockdown care packages.

This feels like a fundamental difference between Greens in Brisbane and Greens parties in other states. We continually make it clear that we don’t accept the narrow limits of what’s purportedly possible within our current system, and we push back assertively whenever we’re accused of being unrealistic or ‘too utopian.’

A lot of southerners don’t seem to understand this dynamic. They’re already theorising that Elizabeth Watson-Brown won Ryan because she was palatable to middleclass centrists who were concerned about climate change. But that’s not the full story.

Queensland is not a conservative state. It is an anti-establishment state where voters have a healthy scepticism of authority and of whoever they perceive as being ‘in charge.’

Whereas down in NSW, Victoria and perhaps Tasmania, the Greens are increasingly seen as part of the political establishment, the Queensland Greens have been able to more clearly position ourselves as anti-establishment. (I should note that a few individual Greens candidates who achieved strong results in other parts of the country have also presented more strongly as ‘system outsiders’ – Celeste Liddle in Cooper springs to mind)

There’s an important distinction between being part of the establishment and being a serious, well-organised political force that’s a credible alternative to the establishment.

To simplistically characterise the massive swings we’re seeing as being purely about ‘climate change’ or ‘sexism’ or narrowly-defined ‘political corruption’ is to overlook the long-term structural collapse in support for both the major parties.

Old political allegiances and loyalties are weakening. Many more voters are up for grabs by anyone who isn’t seen as ‘part of the system,’ and a new contest is emerging between different political orientations – including hardcore fascists, liberal technocrats, and anti-capitalists seeking deeper change – as to who can reach them first.

More and more people are looking for alternatives, and more specifically, for a departure from the status quo.

Here in Queensland, the Greens were clearly offering that. That’s why we won.

Postscript:

While all this sounds very triumphant and self-congratulatory, I should probably note that there are also still some big weaknesses within the Queensland Greens that can’t be ignored…

The ridiculously long working hours that some campaigners adopted in our key campaigns (not just for weeks, but for months) are not necessarily sustainable or scalable. And we are still failing to preselect and elevate enough people of colour and First Nations people as candidates in winnable seats. If anything, our recent successes mean our party will be perceived as even whiter than before. I’ll have more to say on that in the coming weeks.

For now though, I’m feeling pretty damn pleased and excited about what we’ve achieved here in Queensland, and looking forward to what comes next…

Member discussion